Wikipédia:Oficina de tradução/Crise da dívida pública da Zona Euro

Em 1992, membros da União Europeia assinaram o Tratado de Maastricht, sob o qual eles garantiram limitar os gastos deficitários e níveis de dívida. However, in the early 2000s, a number of EU member states were failing to stay within the confines of the Maastricht criteria and turned to securitizing future government revenues to reduce their debts and/or deficits. Sovereigns sold rights to receive future cash flows, allowing governments to raise funds without violating debt and deficit targets, but sidestepping best practice and ignoring internationally agreed standards.[1] This allowed the sovereigns to mask their deficit and debt levels through a combination of techniques, including inconsistent accounting, off-balance-sheet transactions as well as the use of complex currency and credit derivatives structures.[1] Germany, for example, received €15.5 billion from the securitization of pension-related payments from Deutsche Telekom, Deutsche Post, and Deutsche Postbank in 2005‒06, but guaranteed payments so investors bore only the risk of the German government’s credit and the transactions were ultimately recorded in Europe’s fiscal statistics as government borrowing, not asset sales.[2]

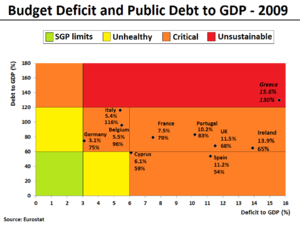

From late 2009, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors as a result of the rising private and government debt levels around the world together with a wave of downgrading of government debt in some European states. Causes of the crisis varied by country. In several countries, private debts arising from a property bubble were transferred to sovereign debt as a result of banking system bailouts and government responses to slowing economies post-bubble. In Greece, high public sector wage and pension commitments helped drive the debt increase.[3] The structure of the Eurozone as a monetary union (i.e., one currency) without fiscal union (e.g., different tax and public pension rules) contributed to the crisis and harmed the ability of European leaders to respond.[4][5] European banks own a significant amount of sovereign debt, such that concerns regarding the solvency of banking systems or sovereigns are negatively reinforcing.[6]

Concerns intensified in early 2010 and thereafter,[7][8] leading European nations to implement a series of financial support measures such as the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

Beside of all the political measures and bailout programmes being implemented to combat the European sovereign debt crisis, the European Central Bank (ECB) has also done its part by lowering interest rates and providing cheap loans of more than one trillion Euros to maintain money flows between European banks. On 6 September 2012, the ECB also calmed financial markets by announcing free unlimited support for all eurozone countries involved in a sovereign state bailout/precautionary programme from EFSF/ESM, through some yield lowering Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT).[9]

The crisis did not only introduce adverse economic effects for the worst hit countries, but also had a major political impact on the ruling governments in 8 out of 17 eurozone countries, leading to power shifts in Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Slovenia, Slovakia, and the Netherlands.

Evolução da crise[editar código-fonte]

In the first few weeks of 2010, there was renewed anxiety about excessive national debt, with lenders demanding ever higher interest rates from several countries with higher debt levels, deficits and current account deficits. This in turn made it difficult for some governments to finance further budget deficits and service existing debt, particularly when economic growth rates were low, and when a high percentage of debt was in the hands of foreign creditors, as in the case of Greece and Portugal.[10]

To fight the crisis some governments have focused on austerity measures (e.g., higher taxes and lower expenses) which has contributed to social unrest and significant debate among economists, many of whom advocate greater deficits when economies are struggling. Especially in countries where budget deficits and sovereign debts have increased sharply, a crisis of confidence has emerged with the widening of bond yield spreads and risk insurance on CDS between these countries and other EU member states, most importantly Germany.[11] By the end of 2011, Germany was estimated to have made more than €9 billion out of the crisis as investors flocked to safer but near zero interest rate German federal government bonds (bunds).[12] By July 2012 also the Netherlands, Austria and Finland benefited from zero or negative interest rates. Looking at short-term government bonds with a maturity of less than one year the list of beneficiaries also includes Belgium and France.[13] While Switzerland (and Denmark)[13] equally benefited from lower interest rates, the crisis also harmed its export sector due to a substantial influx of foreign capital and the resulting rise of the Swiss franc. In September 2011 the Swiss National Bank surprised currency traders by pledging that "it will no longer tolerate a euro-franc exchange rate below the minimum rate of 1.20 francs", effectively weakening the Swiss franc. This is the biggest Swiss intervention since 1978.[14]

Despite sovereign debt having risen substantially in only a few Eurozone countries, with the three most affected countries Greece, Ireland and Portugal collectively only accounting for 6% of the Eurozone's gross domestic product (GDP),[15] it has become a perceived problem for the area as a whole,[16] leading to speculation of further contagion of other European countries and a possible breakup of the Eurozone. In total, the debt crisis forced five out of 17 Eurozone countries to seek help from other nations by the end of 2012.

However, in Mid 2012, due to successful fiscal consolidation and implementation of structural reforms in the countries being most at risk and various policy measures taken by EU leaders and the ECB (see below), financial stability in the Eurozone has improved significantly and interest rates have steadily fallen. This has also greatly diminished contagion risk for other eurozone countries. As of October 2012 only 3 out of 17 eurozone countries, namely Greece, Portugal and Cyprus still battled with long term interest rates above 6%.[17] By early January 2013, successful sovereign debt auctions across the Eurozone but most importantly in Ireland, Spain, and Portugal, shows investors believe the ECB-backstop has worked.[18]

Greece[editar código-fonte]

In the early mid-2000s, Greece's economy was one of the fastest growing in the eurozone and was associated with a large structural deficit.[19] As the world economy was hit by the global financial crisis in the late 2000s, Greece was hit especially hard because its main industries — shipping and tourism — were especially sensitive to changes in the business cycle. The government spent heavily to keep the economy functioning and the country's debt increased accordingly.

On 23 April 2010, the Greek government requested an initial loan of €45 billion from the EU and International Monetary Fund (IMF), to cover its financial needs for the remaining part of 2010.[20][21] A few days later Standard & Poor's slashed Greece's sovereign debt rating to BB+ or "junk" status amid fears of default,[22] in which case investors were liable to lose 30–50% of their money.[22] Stock markets worldwide and the euro currency declined in response to the downgrade.[23]

On 1 May 2010, the Greek government announced a series of austerity measures[24] to secure a three-year €110 billion loan.[25] This was met with great anger by the Greek public, leading to massive protests, riots and social unrest throughout Greece.[26] The Troika (EC, ECB and IMF), offered Greece a second bailout loan worth €130 billion in October 2011, but with the activation being conditional on implementation of further austerity measures and a debt restructure agreement. A bit surprisingly, the Greek prime minister George Papandreou first answered that call, by announcing a December 2011 referendum on the new bailout plan,[27][28] but had to back down amidst strong pressure from EU partners, who threatened to withhold an overdue €6 billion loan payment that Greece needed by mid-December.[27][29] On 10 November 2011 Papandreou resigned following an agreement with the New Democracy party and the Popular Orthodox Rally to appoint non-MP technocrat Lucas Papademos as new prime minister of an interim national union government, with responsibility for implementing the needed austerity measures to pave the way for the second bailout loan.[30][31]

All the implemented austerity measures, have helped Greece bring down its primary deficit - i.e. fiscal deficit before interest payments - from €24.7bn (10.6% of GDP) in 2009 to just €5.2bn (2.4% of GDP) in 2011,[32][33] but as a side-effect they also contributed to a worsening of the Greek recession, which began in October 2008 and only became worse in 2010 and 2011.[34] The Greek GDP had its worst decline in 2011 with −6.9%,[35] a year where the seasonal adjusted industrial output ended 28.4% lower than in 2005,[36][37] and with 111,000 Greek companies going bankrupt (27% higher than in 2010).[38][39] As a result, the seasonal adjusted unemployment rate grew from 7.5% in September 2008 to a record high of 26% in September 2012, while the Youth unemployment rate rose from 22.0% to as high as 57.6%.[40][41] Youth unemployment ratio hit 13 percent in 2011.[42][43]

Overall the share of the population living at "risk of poverty or social exclusion" did not increase noteworthily during the first 2 years of the crisis. The figure was measured to 27.6% in 2009 and 27.7% in 2010 (only being slightly worse than the EU27-average at 23.4%),[44] but for 2011 the figure was now estimated to have risen sharply above 33%.[45] In February 2012, an IMF official negotiating Greek austerity measures admitted that excessive spending cuts were harming Greece.[32]

Some economic experts argue that the best option for Greece and the rest of the EU, would be to engineer an “orderly default”, allowing Athens to withdraw simultaneously from the eurozone and reintroduce its national currency the drachma at a debased rate.[46][47] However, if Greece were to leave the euro, the economic and political consequences would be devastating. According to Japanese financial company Nomura an exit would lead to a 60% devaluation of the new drachma. Analysts at French bank BNP Paribas added that the fallout from a Greek exit would wipe 20% off Greece's GDP, increase Greece's debt-to-GDP ratio to over 200%, and send inflation soaring to 40%-50%.[48] Also UBS warned of hyperinflation, a bank run and even "military coups and possible civil war that could afflict a departing country".[49][50] Eurozone National Central Banks (NCBs) may lose up to €100bn in debt claims against the Greek national bank through the ECB's TARGET2 system. The Deutsche Bundesbank alone may have to write off €27bn.[51]

To prevent this from happening, the troika (EC, IMF and ECB) eventually agreed in February 2012 to provide a second bailout package worth €130 billion,[52] conditional on the implementation of another harsh austerity package, reducing the Greek spendings with €3.3bn in 2012 and another €10bn in 2013 and 2014.[33] For the first time, the bailout deal also included a debt restructure agreement with the private holders of Greek government bonds (banks, insurers and investment funds), to "voluntarily" accept a bond swap with a 53.5% nominal write-off, partly in short-term EFSF notes, partly in new Greek bonds with lower interest rates and the maturity prolonged to 11–30 years (independently of the previous maturity).[53] It is the world's biggest debt restructuring deal ever done, affecting some €206 billion of Greek government bonds.[54] The debt write-off had a size of €107 billion, and caused the Greek debt level to fall from roughly €350bn to €240bn in March 2012, with the predicted debt burden now showing a more sustainable size equal to 117% of GDP by 2020,[55] somewhat lower than the target of 120.5% initially outlined in the signed Memorandum with the Troika.[33][56][57]

Critics such as the director of LSE's Hellenic Observatory argue that the billions of taxpayer euros are not saving Greece but financial institutions,[58] as "more than 80 percent of the rescue package is going to creditors—that is to say, to banks outside of Greece and to the ECB."[59] The shift in liabilities from European banks to European taxpayers has been staggering. One study found that the public debt of Greece to foreign governments, including debt to the EU/IMF loan facility and debt through the eurosystem, increased from €47.8bn to €180.5bn (+132,7bn) between January 2010 and September 2011,[60] while the combined exposure of foreign banks to (public and private) Greek entities was reduced from well over €200bn in 2009 to around €80bn (-120bn) by mid-February 2012.[61]

Mid May 2012 the crisis and impossibility to form a new government after elections and the possible victory by the anti-austerity axis led to new speculations Greece would have to leave the Eurozone shortly due.[62][63][64][65][66] This phenomenon became known as "Grexit" and started to govern international market behaviour.[67][68] However, the center-right's narrow victory in the June 17th election gave hope that Greece would honor its obligations and stay in the Euro-zone.[69]

Due to a delayed reform schedule and a worsened economic recession, the new government immediately asked the Troika to be granted an extended deadline from 2015 to 2017 before being required to restore the budget into a self-financed situation; which in effect was equal to a request of a third bailout package for 2015-16 worth €32.6bn of extra loans.[70][71] On 11 November 2012, facing a default by the end of November, the Greek parliament passed a new austerity package worth €18.8bn,[72] including a "labor market reform" and "midterm fiscal plan 2013-16".[73][74] In return, the Eurogroup agreed on the following day to lower interest rates and prolong debt maturities and to provide Greece with additional funds of around €10bn for a debt-buy-back programme. The latter allowed Greece to retire about half of the €62 billion in debt that Athens owes private creditors, thereby shaving roughly €20 billion off that debt. This should bring Greece's debt-to-GDP ratio down to 124% by 2020 and well below 110% two years later.[75] Without agreement the debt-to-GDP ratio would have risen to 188% in 2013.[76]

Ireland[editar código-fonte]

The Irish sovereign debt crisis was not based on government over-spending, but from the state guaranteeing the six main Irish-based banks who had financed a property bubble. On 29 September 2008, Finance Minister Brian Lenihan, Jnr issued a two-year guarantee to the banks' depositors and bond-holders.[78] The guarantees were subsequently renewed for new deposits and bonds in a slightly different manner. In 2009, an National Asset Management Agency (NAMA), was created to acquire large property-related loans from the six banks at a market-related "long-term economic value".[79]

Irish banks had lost an estimated 100 billion euros, much of it related to defaulted loans to property developers and homeowners made in the midst of the property bubble, which burst around 2007. The economy collapsed during 2008. Unemployment rose from 4% in 2006 to 14% by 2010, while the national budget went from a surplus in 2007 to a deficit of 32% GDP in 2010, the highest in the history of the eurozone, despite austerity measures.[3][80]

With Ireland's credit rating falling rapidly in the face of mounting estimates of the banking losses, guaranteed depositors and bondholders cashed in during 2009-10, and especially after August 2010. (The necessary funds were borrowed from the central bank.) With yields on Irish Government debt rising rapidly it was clear that the Government would have to seek assistance from the EU and IMF, resulting in a €67.5 billion "bailout" agreement of 29 November 2010[81][82] Together with additional €17.5 billion coming from Ireland's own reserves and pensions, the government received €85 billion,[83] of which up to €34 billion was to be used to support the country's ailing financial sector (only about half of this was used in that way following stress tests conducted in 2011).[84] In return the government agreed to reduce its budget deficit to below three percent by 2015.[84] In April 2011, despite all the measures taken, Moody's downgraded the banks' debt to junk status.[85]

In July 2011 European leaders agreed to cut the interest rate that Ireland was paying on its EU/IMF bailout loan from around 6% to between 3.5% and 4% and to double the loan time to 15 years. The move was expected to save the country between 600–700 million euros per year.[86] On 14 September 2011, in a move to further ease Ireland's difficult financial situation, the European Commission announced it would cut the interest rate on its €22.5 billion loan coming from the European Financial Stability Mechanism, down to 2.59 per cent – which is the interest rate the EU itself pays to borrow from financial markets.[87]

The Euro Plus Monitor report from November 2011 attests to Ireland's vast progress in dealing with its financial crisis, expecting the country to stand on its own feet again and finance itself without any external support from the second half of 2012 onwards.[88] According to the Centre for Economics and Business Research Ireland's export-led recovery "will gradually pull its economy out of its trough". As a result of the improved economic outlook, the cost of 10-year government bonds, has already fallen substantially since its record high at 12% in mid July 2011 (see the graph "Long-term Interest Rates"). At 24 July 2012 it was down at a sustainable 6.3%,[89] and it is expected to fall even further to a level of only 4% by 2015.[90]

On 26 July 2012, for the first time since September 2010, Ireland was able to return to the financial markets selling over €5 billion in long-term government debt, with an interest rate of 5.9% for the 5-year bonds and 6.1% for the 8-year bonds at sale.[91]

By 2013 Ireland shouldered €41 billion (42%) of the total cost of the European banking crisis, or nearly €9,000 for each Irish citizen.[92]

Portugal[editar código-fonte]

According to a report by the Diário de Notícias[93] Portugal had allowed considerable slippage in state-managed public works and inflated top management and head officer bonuses and wages in the period between the Carnation Revolution in 1974 and 2010. Persistent and lasting recruitment policies boosted the number of redundant public servants. Risky credit, public debt creation, and European structural and cohesion funds were mismanaged across almost four decades.[94] When the global crisis disrupted the markets and the world economy, together with the US credit crunch and the European sovereign debt crisis, Portugal was one of the first and most affected economies to succumb.

In the summer of 2010, Moody's Investors Service cut Portugal's sovereign bond rating,[95] which led to increased pressure on Portuguese government bonds.[96]

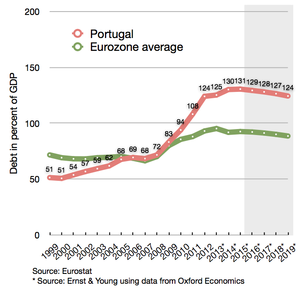

In the first half of 2011, Portugal requested a €78 billion IMF-EU bailout package in a bid to stabilise its public finances.[97] These measures were put in place as a direct result of decades-long governmental overspending and an over bureaucratised civil service. After the bailout was announced, the Portuguese government headed by Pedro Passos Coelho managed to implement measures to improve the State's financial situation and the country started to be seen as moving on the right track. However, this also lead to a strong increase of the unemployment rate to over 15 percent in the second quarter 2012 and it is expected to rise even further in the near future.[98]

Portugal’s debt was in September 2012 forecast by the Troika to peak at around 124% of GDP in 2014, followed by a firm downward trajectory after 2014. Previously the Troika had predicted it would peak at 118.5% of GDP in 2013, so the developments proved to be a bit worse than first anticipated, but the situation was described as fully sustainable and progressing well. As a result from the slightly worse economic circumstances, the country has been given one more year to reduce the budget deficit to a level below 3% of GDP, moving the target year from 2013 to 2014. The budget deficit for 2012 has been forecast to end at 5%. The recession in the economy is now also projected to last until 2013, with GDP declining 3% in 2012 and 1% in 2013; followed by a return to positive real growth in 2014.[99]

As part of the bailout programme, Portugal is required to regain complete access to financial markets starting from September 2013. The first step has been successfully completed on 3 October 2012, when the country managed to regain partly market access. Once Portugal regains complete access it is expected to benefit from interventions by the ECB, which announced support in the form of some yield-lowering bond purchases (OMTs),[99] to bring governmental interest rates down to sustainable levels. A peak for the Portuguese 10-year governmental interest rates happened on 30 January 2012, where it reached 17.3% after the rating agencies had cut the governments credit rating to "non-investment grade" (also referred to as "junk").[100] As of December 2012, it has been more than halved to only 7%.[101]

Spain[editar código-fonte]

Spain had a comparatively low debt level among advanced economies prior to the crisis.[102] Its public debt relative to GDP in 2010 was only 60%, more than 20 points less than Germany, France or the US, and more than 60 points less than Italy, Ireland or Greece.[103][104] Debt was largely avoided by the ballooning tax revenue from the housing bubble, which helped accommodate a decade of increased government spending without debt accumulation.[105] When the bubble burst, Spain spent large amounts of money on bank bailouts. In May 2012, Bankia received a 19 billion euro bailout,[106] on top of the previous 4.5 billion euros to prop up Bankia.[107] Questionable accounting methods disguised bank losses.[108] During September 2012, regulators indicated that Spanish banks required €59 billion (USD $77 billion) in additional capital to offset losses from real estate investments.[109]

The bank bailouts and the economic downturn increased the country's deficit and debt levels and led to a substantial downgrading of its credit rating. To build up trust in the financial markets, the government began to introduce austerity measures and it amended the Spanish Constitution in 2011 to require a balanced budget at both the national and regional level by 2020. The amendment states that public debt can not exceed 60% of GDP, though exceptions would be made in case of a natural catastrophe, economic recession or other emergencies.[110][111] As one of the largest eurozone economies (larger than Greece, Portugal and Ireland combined[112]) the condition of Spain's economy is of particular concern to international observers. Under pressure from the United States, the IMF, other European countries and the European Commission[113][114] the Spanish governments eventually succeeded in trimming the deficit from 11.2% of GDP in 2009 to an expected 5.4% in 2012.[112]

Nevertheless, in June 2012, Spain became a prime concern for the Euro-zone[115] when interest on Spain’s 10-year bonds reached the 7% level and it faced difficulty in accessing bond markets. This led the Eurogroup on 9 June 2012 to grant Spain a financial support package of up to €100 billion.[116] The funds will not go directly to Spanish banks, but be transferred to a governmently owned Spanish fund responsible to conduct the needed bank recapitalisations (FROB), and thus it will be counted for as additional sovereign debt in Spain's national account.[117][118][119] An economic forecast in June 2012highlighted the need for the arranged bank recapitalisation support package, as the outlook promised a negative growth rate of 1.7%, unemployment rising to 25%, and a continued declining trend for housing prices.[112] In September 2012 the ECB removed some of the pressure from Spain on financial markets, when it announced its "unlimited bond-buying plan", to be initiated if Spain would sign a new sovereign bailout package with EFSF/ESM.[120][121]

As of October 2012, the Troika (EC, ECB and IMF) is indeed in negotiations with Spain to establish an economic recovery program, which is required if the country should request a bailout package for the sovereign state from ESM. Reportedly Spain, in addition to the €100bn "bank recapitalisation" package arranged for in June 2012,[122] now also seeks sovereign financial support from a "Precautionary Conditioned Credit Line" (PCCL) package.[123] If Spain receives a PCCL package, irrespective to what extent it subsequently decides to draw on this established credit line, Spain would immediately qualify to receive "free" additional financial support from ECB, in the form of some unlimited yield-lowering bond purchases (OMT).[124][125] According to recent statements by the Prime Minister, the country as of December 2012 still consider perhaps to request a PCCL sovereign bailout package in 2013, but only if developments at financial markets will promise Spain a significant financial advantage of doing so. As of 7 December 2012, the yield of 10-year government bonds had declined to 5.4%.[126]

According to the latest debt sustainability analysis published by the European Commission in October 2012, the fiscal outlook for Spain, if assuming the country will stick to the fiscal consolidation path and targets outlined by the country's current EDP programme, will result in a debt-to-GDP ratio reaching its maximum at 110% in 2018 - followed by a declining trend in subsequent years. In regards of the structural deficit the same outlook has promised, that it will gradually decline to comply with the maximum 0.5% level required by the Fiscal Compact in 2022/2027.[127]

Cyprus[editar código-fonte]

Referências

- ↑ a b "How Europe’s Governments have Enronized their debts," Mark Brown and Alex Chambers, Euromoney, September 2005

- ↑ "Securitization: Sovereigns window-dress national finances," Euromoney, July 2005

- ↑ a b Lewis, Michael (2011). Boomerang – Travels in the New Third World. [S.l.]: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-08181-7]

- ↑ Heard on Fresh Air from WHYY (4 de outubro de 2011). «NPR-Michael Lewis-How the Financial Crisis Created a New Third World-October 2011». Npr.org. Consultado em 7 de julho de 2012

- ↑ Koba, Mark (13 de junho de 2012). «CNBC-Europe's Economic Crisis-What You Need to Know-Mark Thoma-June 13, 2012». Finance.yahoo.com. Consultado em 7 de julho de 2012

- ↑ Seth W. Feaster; Nelson D. Schwartz; Tom Kuntz (22 de outubro de 2011). «NYT-It's All Connected-A Spectators Guide to the Euro Crisis». New York Times. Nytimes.com. Consultado em 14 de maio de 2012 Texto "location?New York" ignorado (ajuda)

- ↑ George Matlock (16 de fevereiro de 2010). «Peripheral euro zone government bond spreads widen». Reuters. Consultado em 28 de abril de 2010

- ↑ «Acropolis now». The Economist. 29 de abril de 2010. Consultado em 22 de junho de 2011

- ↑ "Technical features of Outright Monetary Transactions", ECB Press Release, 6 September 2012

- ↑ Ventura, Luca; Aridas, Tina (dezembro de 2011). «Public Debt by Country | Global Finance». Gfmag.com. Consultado em 19 de maio de 2011

- ↑ Oakley, David; Hope, Kevin (18 de fevereiro de 2010). «Gilt yields rise amid UK debt concerns». Financial Times. Consultado em 15 de abril de 2011

- ↑ Valentina Pop (9 de novembro de 2011). «Germany estimated to have made €9 billion profit out of crisis». EUobserver. Consultado em 8 de dezembro de 2011

- ↑ a b «Immer mehr Länder bekommen Geld fürs Schuldenmachen». Der Standard Online. 17 de julho de 2012. Consultado em 30 de julho de 2012

- ↑ Swiss Pledge Unlimited Currency Purchases Bloomberg, 6 September 2011, Retrieved 6 September 2011

- ↑ «The Euro's PIG-Headed Masters». Project Syndicate. 3 de junho de 2011

- ↑ «How the Euro Became Europe's Greatest Threat». Der Spiegel. 20 de junho de 2011

- ↑ «Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States». ECB. 13 de novembro de 2012. Consultado em 13 de novembro de 2012

- ↑ Richard Barley (24 de janeiro de 2013). «Euro-Zone Bonds Find Favor». Wall Street Journal

- ↑ «Crisis in Euro-zone—Next Phase of Global Economic Turmoil». Competition master date =. Consultado em 24 de fevereiro de 2012

- ↑ Ziotis, Christos; Weeks, Natalie (20 de abril de 2010). «Greek Bailout Talks Could Take Three Weeks as Bond Repayment Looms in May». Bloomberg L.P.

- ↑ «Greece Seeks Activation of €45bn EU/IMF Aid Package». The Irish Times. 4 de abril de 2010

- ↑ a b Ewing, Jack; Healy, Jack (27 de abril de 2010). «Cuts to Debt Rating Stir Anxiety in Europe». The New York Times. Consultado em 6 de maio de 2010

- ↑ «Greek bonds rated 'junk' by Standard & Poor's». BBC. 27 de abril de 2010. Consultado em 6 de maio de 2010

- ↑ Predefinição:Gr icon«Fourth raft of new measures». In.gr. 2 de maio de 2010. Consultado em 6 de maio de 2010

- ↑ «Revisiting Greece». The Observer at Boston College. 2 de novembro de 2011

- ↑ Judy Dempsey (5 de maio de 2010). «Three Reported Killed in Greek Protests». The New York Times. Consultado em 5 de maio de 2010

- ↑ a b Rachel Donadio; Niki Kitsantonis (3 de novembro de 2011). «Greek Leader Calls Off Referendum on Bailout Plan». The New York Times. Consultado em 29 de dezembro de 2011

- ↑ «Greek cabinet backs George Papandreou's referendum plan». BBC News. 2 de novembro de 2011. Consultado em 29 de dezembro de 2011

- ↑ «Papandreou calls off Greek referendum». UPI. 3 de novembro de 2011. Consultado em 29 de dezembro de 2011

- ↑ Helena Smith (10 de novembro de 2011). «Lucas Papademos to lead Greece's interim coalition government». The Guardian. Consultado em 29 de dezembro de 2011

- ↑ Leigh Phillips (11 de novembro de 2011). «ECB man to rule Greece for 15 weeks». EUobserver. Consultado em 29 de dezembro de 2011

- ↑ a b Smith, Helena (1 de fevereiro de 2012). «IMF official admits: austerity is harming Greece». The Guardian. Athens. Consultado em 1 de fevereiro de 2012

- ↑ a b c «Der ganze Staat soll neu gegründet werden». Sueddeutsche. 13 de fevereiro de 2012. Consultado em 13 de fevereiro de 2012 Erro de citação: Código

<ref>inválido; o nome "SZ-staat-neu" é definido mais de uma vez com conteúdos diferentes - ↑ «QUARTERLY NATIONAL ACCOUNTS: 4th quarter 2011 (Provisional)» (PDF). Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 9 de março de 2012. Consultado em 9 de março de 2012

- ↑ «EU interim economic forecast -February 2012» (PDF). European Commission. 23 de fevereiro de 2012. Consultado em 2 de março de 2012

- ↑ «Eurostat Newsrelease 24/2012: Industrial production down by 1.1% in euro area in December 2011 compared with November 2011» (PDF). Eurostat. 14 de fevereiro de 2012. Consultado em 5 de março de 2012

- ↑ «Eurozone debt crisis live: UK credit rating under threat amid Moody's downgrade blitz». The Guardian. 14 de fevereiro de 2012. Consultado em 14 de fevereiro de 2012

- ↑ «Pleitewelle rollt durch Südeuropa». Sueddeutsche Zeitung. 7 de fevereiro de 2012. Consultado em 9 de fevereiro de 2012

- ↑ Hatzinikolaou, Prokopis (7 de fevereiro de 2012). «Dramatic drop in budget revenues». Ekathimerini. Consultado em 16 de fevereiro de 2012

- ↑ «Eurostat Newsrelease 31/2012: Euro area unemployment rate at 10.7% in January 2012» (PDF). Eurostat. 1 de março de 2012. Consultado em 5 de março de 2012

- ↑ «Seasonally adjusted unemployment rate». Google/Eurostat. 10 de novembro de 2011. Consultado em 7 de fevereiro de 2012

- ↑ «Youth employment is bad - but not as bad as we're told». The New York Times. 26 de junho de 2012

- ↑ «Unemployment statistics». Eurostat. Abril de 2012. Consultado em 27 de junho de 2012

- ↑ «Eurostat Newsrelease 21/2012: In 2010, 23% of the population were at risk of poverty or social exclusion» (PDF). Eurostat. 8 de fevereiro de 2012. Consultado em 5 de março de 2012

- ↑ M. Nicolas J. Firzli, "Greece and the Roots the EU Debt Crisis" The Vienna Review, March 2010

- ↑ Nouriel Roubini (28 de junho de 2010). «Greece's best option is an orderly default». Financial Times. Consultado em 24 de setembro de 2011

- ↑ Kollewe, Julia (13 de maio de 2012). «How Greece could leave the eurozone – in five difficult steps». The Guardian. UK. Consultado em 16 de maio de 2012

- ↑ «Greece». New York Times. 22 de janeiro de 2012. Consultado em 23 de janeiro de 2012

- ↑ «Pondering a Dire Day: Leaving the Euro». New York Times. 12 de dezembro de 2011. Consultado em 23 de janeiro de 2012

- ↑ «Ein Risiko von 730 Milliarden Euro». Sueddeutsche. 2 de agosto de 2012. Consultado em 3 de agosto de 2012

- ↑ «"A common response to the crisis situation" - European Council webpage». European-council.europa.eu. 21 de julho de 2011. Consultado em 16 de maio de 2012

- ↑ Willem Sels (27 de fevereiro de 2012). «Greek rescue package is no long term solution, says HSBC's Willem Sels». Investment Europe. Consultado em 3 de março de 2012

- ↑ «Insight: How the Greek debt puzzle was solved». Reuters. 29 de fevereiro de 2012. Consultado em 29 de fevereiro de 2012

- ↑ «Griechenland spart sich auf Schwellenland-Niveau herunter». Sueddeutsche. 13 de março de 2012. Consultado em 13 de março de 2012

- ↑ «Eurogroup statement» (PDF). Eurogroup. 21 de fevereiro de 2012. Consultado em 21 de fevereiro de 2012

- ↑ «Greece bailout: six key elements of the deal». The Guardian. 21 de fevereiro de 2012. Consultado em 21 de fevereiro de 2012

- ↑ Kevin Featherstone (23 de março de 2012). «Are the European banks saving Greece or saving themselves?». Greece@LSE. LSE. Consultado em 27 de março de 2012

- ↑ «Greek aid will go to the banks». Presseurop. 9 de março de 2012. Consultado em 12 de março de 2012

- ↑ Whittaker, John (2011). «Eurosystem debts, Greece, and the role of banknotes» (PDF). Lancaster University Management School. Consultado em 2 April 2012 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Stephanie Flanders (16 de fevereiro de 2012). «Greece: Costing the exit». BBC News. Consultado em 5 de abril de 2012

- ↑ «A Greek Reprieve: The Germans might have preferred a victory by the left in Athens». Wall Street Journal. 18 de junho de 2012

- ↑ «Huge Sense of Doom Among 'Grexit' Predictions». Cnbc.com. Consultado em 17 de maio de 2012

- ↑ Ross, Alice. «Grexit and the euro: an exercise in guesswork». Financial Times. Consultado em 16 de maio de 2012

- ↑ Alexander Boot. «From 'Grexit' to 'Spain in the neck': It's time for puns, neologisms and break-ups». Mail Online - Dailymail.co.uk. Consultado em 16 de maio de 2012

- ↑ «Grexit Greek Exit From The Euro». Maxfarquar.com. Consultado em 16 de maio de 2012

- ↑ «Grexit - What does Grexit mean?». Gogreece.about.com. 10 de abril de 2012. Consultado em 16 de maio de 2012

- ↑ Buiter, Willem. «Rising Risks of Greek Euro Area Exit» (PDF). Willem Buiter. Consultado em 17 de maio de 2012. Cópia arquivada em 30 de maio de 2012

- ↑ Anthee Carassava and Henry Chu (18 de junho de 2012). «Pro-Eurozone conservatives take first place in Greece election». Los Angles Times

- ↑ «Troika report (Draft version 11 November 2012)» (PDF). European Commission. 11 de novembro de 2012. Consultado em 12 de novembro de 2012

- ↑ «Greece seeks 2-year austerity extension». Financial Times. 14 de agosto de 2012. Consultado em 1 de setembro de 2012

- ↑ «Samaras raises alarm about lack of liquidity, threat to democracy». Ekathimerini. 5 de outubro de 2012. Consultado em 7 de outubro de 2012

- ↑ «Unsustainable debt, restructuring or new stimulus package» (em Greek). Kathimerini. 4 de outubro de 2012. Consultado em 4 de outubro de 2012

- ↑ «One step forward, two back for Greece on debt». eKathimerini. 3 de outubro de 2012. Consultado em 4 de outubro de 2012

- ↑ «Greece's Buyback Effort Advances». Wall Street Journal. 11 de dezembro de 2012

- ↑ «European economic forecast - autumn 2012» (PDF). European Commission. 7 de novembro de 2012. Consultado em 7 de novembro de 2012

- ↑ «General government surplus/deficit as percentage of GDP». Google/Eurostat. 27 de outubro de 2012. Consultado em 10 de novembro de 2012

- ↑ McConnell, Daniel (13 de fevereiro de 2011). «Remember how Ireland was ruined by bankers». Independent News & Media PLC. Consultado em 6 de junho de 2012

- ↑ «Brian Lenihan, Jr, Obituary and Info». The Journal.ie. Consultado em 30 de junho de 2012

- ↑ «CIA World Factbook-Ireland-Retrieved 2 December 2011». Cia.gov. Consultado em 14 de maio de 2012

- ↑ «The money pit». The Economist

- ↑ «"Irish Times" timeline on financial events 2008–2010». Irishtimes.com. 11 de novembro de 2010. Consultado em 14 de maio de 2012

- ↑ EU unveils Irish bailout, CNN.com, 2 December 2010

- ↑ a b Gammelin, Cerstin; Oldag, Andreas (21 de novembro de 2011). «Ihr Krisenländer, schaut auf Irland!». Süddeutsche Zeitung. Consultado em 21 de novembro de 2011

- ↑ «Moody's cuts all Irish banks to junk status». RTE. 18 de abril de 2011. Consultado em 6 de junho de 2012

- ↑ Hayes, Cathy (21 de julho de 2011). «Ireland gets more time for bailout repayment and interest rate cut». Irish Central. Consultado em 6 de junho de 2012

- ↑ Reilly, Gavan. «European Commission reduces margin on Irish bailout to zero». The Journal

- ↑ «Euro Plus Monitor 2011 (p. 55)». The Lisbon Council. 15 de novembro de 2011. Consultado em 17 de novembro de 2011

- ↑ «Bonds - Ten year Government spreads». Financial Times. 24 de julho de 2012. Consultado em 24 de julho de 2012

- ↑ Mason, Daniel (2 de setembro de 2011). «Ireland set for strong recovery after bail-out». Consultado em 17 de novembro de 2011

- ↑ O'Donovan, Donal (27 de julho de 2012). «Ireland borrows over €5bn on first day back in bond markets». Consultado em 30 de julho de 2012

- ↑ Taft, Michael (15 de janeiro de 2013). «Column: How much has Ireland paid for the EU banking crisis?». Consultado em 28 de fevereiro de 2013

- ↑ (português) "O estado a que o Estado chegou" no 2.º lugar do top, Diário de Notícias (2 March 2011)

- ↑ (português) "O estado a que o Estado chegou" no 2.º lugar do top, Diário de Notícias (2 March 2012)

- ↑ Bond credit ratings

- ↑ BBC News -Moody's downgrades Portugal debt

- ↑ «Portugal requests bailout». Christian Science Monitor. Consultado em 30 de junho de 2012

- ↑ Portugal Q2 Unemployment Rate Rises To Record High, RTTNews (August 14, 2012)

- ↑ a b «Portugal seeks market access with $5 bln bond exchange». Kathimerini (English Edition). 3 de outubro de 2012. Consultado em 17 de outubro de 2012

- ↑ «Data archive for bonds and rates (Ten-year government bond spreads on 30 January 2012)» (PDF). Financial Times. 30 de janeiro de 2012. Consultado em 24 de novembro de 2012

- ↑ «Portugal 10-Year Futures Historical Data». ForexPros.com. 24 de novembro de 2012. Consultado em 24 de novembro de 2012

- ↑ Murado, Miguel-Anxo (1 de maio de 2010). «Repeat with us: Spain is not Greece». The Guardian. London

- ↑ «"General government gross debt", Eurostat table, 2003–2010». Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Consultado em 16 de maio de 2012

- ↑ «Strong core, pain on the periphery». The Economist

- ↑ Juan Carlos Hidalgo (31 de maio de 2012). «Looking at Austerity in Spain». Cato Institute

- ↑ Christopher Bjork, Jonathan House, and Sara Schaefer Muñoz (25 de maio de 2012). «Spain Pours Billions Into Bank». Wall Street Journal. Consultado em 26 de maio de 2012

- ↑ «Spain's Bankia Seeking $19B in Government Aid». Fox Business. Reuters. 25 de maio de 2012. Consultado em 25 de maio de 2012

- ↑ Jonathan Weil (14 de junho de 2012). «The EU Smiled While Spain's Banks Cooked the Books». Bloomberg

- ↑ Bloomberg-Ben Sills-Spain to Borrow $267B of Debt Amidst Rescue Pressure-September 2012

- ↑ Mamta Badkar (26 de agosto de 2011). «Here Are The Details From Spain's New Balanced Budget Amendment - Business Insider». Articles.businessinsider.com. Consultado em 14 de maio de 2012

- ↑ Giles, Tremlett, "Spain changes constitution to cap budget deficit", Guardian , 26 August 2011

- ↑ a b c Charles Forell and Gabriele Steinhauser (11 de junho de 2012). «Latest Europe Rescue Aims to Prop Up Spain». Wall Street Journal

- ↑ «Obama calls for 'resolute' spending cuts in Spain». EUObserver. 12 de maio de 2010. Consultado em 12 de maio de 2010

- ↑ «Spain Lowers Public Wages After EU Seeks Deeper Cuts». Bloomberg Business Week. 12 de maio de 2010. Consultado em 12 de maio de 2010

- ↑ Ian Traynor and Nicholas Watt (6 de junho de 2012). «Spain calls for new tax pact to save euro: Madrid calls for Europe-wide plan but resists 'humiliation' of national bailout». The Guardian

- ↑ http://www.diariodeavisos.com/comunicado-integro-del-eurogrupo-sobre-el-rescate-a-la-banca-espanola/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter

- ↑ «The Spanish bail-out: Going to extra time». The Economist. 16 de junho de 2012

- ↑ Matina Stevis (6 de julho de 2012). «Doubts Emerge in Bloc's Rescue Deal». Wall Street Journal

- ↑ Bruno Waterfield (29 de junho de 2012). «Debt crisis: Germany caves in over bond buying, bank aid after Italy and Spain threaten to block 'everything'». Telegraph

- ↑ Stephen Castle and Melissa Eddy (7 Sept 2012). «Bond Plan Lowers Debt Costs, but Germany Grumbles». New York Times Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Emese Bartha; Jonathan House (Sept 18, 2012). «Spain Debt Sells Despite Bailout Pressure». Wall Street Journal Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ «FAQ about European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the new ESM» (PDF). EFSF. 3 de agosto de 2012. Consultado em 19 de agosto de 2012

- ↑ «Spain to ask for bailout next month». The Telegraph. 15 de outubro de 2012. Consultado em 15 de outubro de 2012

- ↑ «Opposition wanes to Spanish aid request». Financial Times. 16 de outubro de 2012. Consultado em 16 de outubro de 2012

- ↑ «Spain prepares to make rescue request». Financial Times. 24 de outubro de 2012. Consultado em 27 de outubro de 2012

- ↑ «Spain 10-Year Bond Yield or Futures - Historical Data». Investing.com. 8 de dezembro de 2012. Consultado em 9 de dezembro de 2012

- ↑ «European Economy Occasional Papers 118: The Financial Sector Adjustment Programme for Spain» (PDF). European Commission. 16 de outubro de 2012. Consultado em 28 de outubro de 2012