Usuário(a):Luis Otávio Whately/Testes

Esta é uma página de testes de Luis Otávio Whately, uma subpágina da principal. Serve como um local de testes e espaço de desenvolvimento, desta feita não é um artigo enciclopédico. Para uma página de testes sua, crie uma aqui. Como editar: Tutorial • Guia de edição • Livro de estilo • Referência rápida Como criar uma página: Guia passo a passo • Como criar • Verificabilidade • Critérios de notoriedade |

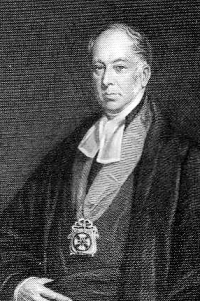

Richard Whately (01 Fevereiro 1787 – 08 Outubro 1863) foi um retórico, lógico, economista, e teólogo inglês que serviu como Arcebispo de Dublin para a Igreja Anglicana.

Biografia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ele nasceu em Londres, filho do Rev. Dr. Joseph Whately (17 de março de 1730 - 13 de março de 1797). Ele foi educado em uma escola particular perto de Bristol, e no Oriel College, Oxford. Richard Whately obteve duas vezes honras de segunda classe e o prêmio para o melhor ensaio em Inglês; em 1811 ele foi eleito Fellow do Oriel College, e em 1814 tomou ordens sacras. Após seu casamento, em 1821, estabeleceu-se em Oxford.

Em agosto de 1823, ele se mudou para Halesworth em Suffolk, mas em 1825, tendo sido nomeado diretor de St. Alban Hall, voltou para Oxford. Ele encontrou muito para reformar por lá, e o deixou um lugar bem diferente. Ele tinha, inicialmente, um relacionamento amigável com John Henry Newman, mas este mudou conforme a divergência em seus pontos de vista tornou-se aparente; Newman, depois, falou de sua Universidade Católica de continuar em Dublin a luta contra Whately que ele havia começado em Oxford.

Em 1829 Whately foi eleito para o cargo de professor de economia política na Universidade de Oxford, em substituição a Nassau William sênior. O seu mandato foi interrompido por sua nomeação para o cargo de arcebispado de Dublin em 1831. Ele publicou apenas um curso de Conferências Introdutórias (1832), mas um de seus primeiros atos em indo para Dublin foi estabelecer uma cadeira de economia política no Trinity College.

Arcebispo de Dublin[editar | editar código-fonte]

A nomeação de Whately por Lord Grey (Charles Grey, segundo Earl Grey) para a Sé de Dublin veio como uma surpresa política. O idoso bispo Henry Bathurst tinha virado o cargo para baixo. A nova administração do partido Whig considerou Whately, bem conhecido no Holland House de Londres, e muito eficaz em um discurso sobre dízimos, proferido diante uma comissão parlamentar, uma opção aceitável. Nos bastidores Thomas Hyde Villiers fez lobby em nome de Whately junto Denis Le Marchant, primeiro secretário do Lord Chanceler Brougham dos Whigs.[1] A nomeação foi contestada na Câmara dos Lordes, mas sem sucesso.

In Ireland, Whately's bluntness and his lack of a conciliatory manner caused opposition from his clergy. He attempted to establish a national and non-sectarian system of education. He enforced strict discipline in his diocese; and he published a statement of his views on Sabbath (Thoughts on the Sabbath, 1832). He lived in Redesdale House in Kilmacud, just outside Dublin, where he could garden. Questions of tithes, reform of the Irish church and of the Irish Poor Laws, and, in particular, the organisation of national education occupied much of his time. He discussed other public questions, for example, the subject of transportation and the general question of secondary punishments.

His scheme of religious instruction for Protestants and Catholics alike was carried out for a number of years, but in 1852 it broke down owing to the opposition of the new Catholic archbishop of Dublin, Paul Cullen (cardinal)|Paul Cullen, and Whately felt himself constrained to withdraw from the Education Board. From the beginning Whately gave offence by supporting state endowment of the Catholic clergy. During the famine years of 1846 and 1847 the archbishop and his family tried to alleviate the miseries of the people. He was the first president of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland between 1847 and 1863.

On 27 March 1848, Whately became a member of the Canterbury Association.[2]

Morte[editar | editar código-fonte]

From 1856 onwards symptoms of decline began to manifest themselves in a paralytic affection of the left side. Still he continued the active discharge of his public duties till the summer of 1863, when he was prostrated by an ulcer in the leg, and after several months of acute suffering he died on 8 October 1863.

Trabalhos[editar | editar código-fonte]

During his residence at Oxford Whately wrote his tract, Historic Doubts relative to Napoleon Bonaparte, a jeu d'ésprit directed against excessive scepticism as applied to the Gospel history. In 1822 he was appointed Bampton lecturer. The lectures, On the Use and Abuse of Party Spirit in Matters of Religion, were published in the same year.

In 1825 he published a series of Essays on Some of the Peculiarities of the Christian Religion, followed in 1828 by a second series On some of the Difficulties in the Writings of St Paul, and in 1830 by a third On the Errors of Romanism traced to their Origin in Human Nature. While he was at St Alban Hall (1826) the work appeared which is perhaps most closely associated with his name—a treatise on logic entitled Elements of Logic. In the preface to the Elements of Logic, Whately wrote that the substance of the treatise was drawn from an article written by himself, entitled Logic, which had already been published in the Encyclopædia Metropolitana.[3] The Elements of Logic gave a great impetus to the study of logic throughout Britain and the United States of America. Indeed, the highly original and influential American logician, Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914), wrote that his lifelong fascination with logic began when he read Whately's Elements of Logic as a 12-year-old boy.[4] Whately also contributed an article to the Encyclopædia Metropolitana entitled Rhetoric. This article was also adapted into a book, called Elements of Rhetoric, which was published in 1828.

In 1837 Whately wrote his handbook of Christian Evidences, which was translated during his lifetime into more than a dozen languages. At a later period he also wrote, in a similar form, Easy Lessons on Reasoning, on Morals, on Mind and on the British Constitution. Among his other works may be mentioned Charges and Tracts (1836), Essays on Some of the Dangers to Christian Faith (1839), The Kingdom of Christ (1841). He also edited Bacon's Essays, Paley's Evidences and Paley's Moral Philosophy.

- 1822 "On the Use and Abuse of Party Spirit in Matters of Religion" (Bampton Lectures)

- 1825 "Essays on Some of the Peculiarities of the Christian Religion"

- 1826 "Elements of Logic"

- 1828 "Elements of Rhetoric"

- 1828 "On some of the Difficulties in the Writings of St Paul"

- 1830 "On the Errors of Romanism traced to their Origin in Human Nature"

- 1832 "Introductory Lectures"

- 1832 A view of the Scripture revelations concerning a future state: lectures advancing belief in Christian mortalism.

- 1832 "Thoughts on the Sabbath"

- 1836 "Charges and Tracts"

- 1837 "Christian Evidences"

- 1839 "Essays on Some of the Dangers to Christian Faith"

- 1841 "The Kingdom of Christ"

- 1845 onwards "Easy Lessons": on Reasoning, On Morals, On Mind, and on the British Constitution

- 1849 "Historic Doubts relative to Napoleon Bonaparte"

Legado[editar | editar código-fonte]

Whately was a great talker, much addicted in early life to argument, in which he used others as instruments on which to hammer out his own views, and as he advanced in life much given to didactic monologue. He had a keen wit, whose sharp edge often inflicted wounds never deliberately intended by the speaker, a healthy appetite and a wholly uncontrollable love of punning. Whately often offended people by the extreme unconventionality of his manners. When at Oxford his white hat, rough white coat, and huge white dog earned for him the sobriquet of the White Bear, and he outraged the conventions of the place by exhibiting the exploits of his climbing dog in Christchurch Meadow.

Whately was a devout Christian, but opposed to mere outward displays of faith. While sharing the Evangelical belief in Scripture as the sole instrument of salvation, and also like the Evangelicals being a Biblical literalist, he disagreed with the Evangelical party on the applicability of the Mosaic laws to Christians and generally favoured a more intellectual approach to religion than most of the Evangelicals of his period. He also disagreed with the Tractarian emphasis on ritual and church authority. Instead, he emphasised careful reading and understanding of the Bible and a sincere attempt to follow the precepts and example of Jesus in one's personal life. He offended Tractarian and Evangelical parties equally in his insistence that imposing civil penalties for religious beliefs led to a mere nominal Christianity. He fully supported complete religious liberty, civil rights, and freedom of speech for dissenters, Roman Catholics, Jews, and even atheists, a position that outraged many of his compatriots.

He took a practical, almost business-like view of Christianity, which seemed to High Churchmen and Evangelicals alike little better than Rationalism. In this they did Whately less than justice, for his religion was very real and genuine. But he may be said to have continued the typical Christianity of the 18th century—that of the theologians who went out to fight the Rationalists with their own weapons. It was to Whately essentially a belief in certain matters of fact, to be accepted or rejected after an examination of "evidences." Hence his endeavour always is to convince the logical faculty, and his Christianity inevitably appears as a thing of the intellect rather than of the heart. Whately's qualities are exhibited at their best in his Logic. He wrote nothing better than the luminous Appendix to this work on Ambiguous Terms.

In 1864 his daughter published Miscellaneous Remains from his commonplace book and in 1866 his Life and Correspondence in two volumes. The Anecdotal Memoirs of Archbishop Whately, by William John Fitzpatrick (1864), enliven the picture.

Whately was perhaps the single most important figure in the revival of Aristotelian logic in the early nineteenth century. He was also important in the history of political economy, founding what is now known as the Whately Chair of political economy at Trinity College, Dublin. His Elements of Rhetoric remains widely read by rhetorical scholars in English and Communication Departments, especially in North America, and he continues to have a significant influence on rhetorical theory, especially in thought about presumption, burden of proof, and testimony.

A programme in the BBC television series Who Do You Think You Are? (British TV series)|Who Do You Think You Are?, broadcast on 2 March 2009, uncovered that Richard Whately was an ancestor of British actor Kevin Whately.

Notas[editar | editar código-fonte]

- ↑ David de Giustino, Finding an Archbishop: The Whigs and Richard Whately in 1831, Church History, Vol. 64, No. 2 (June., 1995), pp. 218–236. Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Society of Church History. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3167906

- ↑ Blain, Michael (2007). «Reverend» (PDF). The Canterbury Association (1848–1852): A Study of Its Members' Connections. 87 páginas. Consultado em 19 January 2010 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Whately, Richard, Elements of Logic, p.vii, Longman, Greens and Co. (9th Edition, London, 1875)

- ↑ Fisch, Max, "Introduction", W 1:xvii, find phrase "One episode".

Referências[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Webb, Alfred (1878). "Wikisource link to Whately, Richard". A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M. H. Gill & son. Wikisource

Leitura Adicional[editar | editar código-fonte]

A modern biography is Richard Whately: A Man for All Seasons by Craig Parton ISBN 1-896363-07-5. See also Donald Harman Akenson A Protestant in Purgatory: Richard Whately, Archbishop of Dublin (South Bend, Indiana 1981)

- Einhorn, Lois J. "Consistency in Richard Whately: The Scope of His Rhetoric." Philosophy & Rhetoric 14 (Spring 1981): 89–99.

- Einhorn, Lois J. "Richard Whately's Public Persuasion: The Relationship between His Rhetorical Theory and His Rhetorical Practice." Rhetorica 4 (Winter 1986): 47–65.

- Einhorn, Lois J. "Did Napoleon Live? Presumption and Burden of Proof in Richard Whately's Historic Doubts Relative to Napoleon Boneparte." Rhetoric Society Quarterly 16 (1986): 285–97.

- Giustino, David de. "Finding an archbishop: the Whigs and Richard Whately in 1831." Church History 64 (1995): 218–36.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Richard Whately: Religious Controversialist of the Nineteenth Century." Prose Studies: 1800–1900 2 (1979): 160–87.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Archbishop Whately: Human Nature and Christian Assistance." Church History 50.2 (1981): 166–189.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Richard Whately on the Nature of Human Knowledge in Relation to the Ideas of his Contemporaries." Journal of the History of Ideas 42.3 (1981): 439–455.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Richard Whately's Theory of Rhetoric." In Explorations in Rhetoric. ed. R. McKerrow. Glenview IL: Scott, Firesman, & Co., 1982.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Richard Whately and the Revival of Logic in Nineteenth-Century England." Rhetorica 5 (Spring 1987): 163–85.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Whately's Philosophy of Language." The Southern Speech Communication Journal 53 (1988): 211–226.

- Poster, Carol. "Richard Whately and the Didactic Sermon." The History of the Sermon: The Nineteenth Century. Ed. Robert Ellison. Leiden: Brill, 2010: 59–113.

- Poster, Carol. "An Organon for Theology: Whately's Rhetoric and Logic in Religious Context". Rhetorica 24:1 (2006): 37–77.

- Sweet, William. "Paley, Whately, and 'enlightenment evidentialism'". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 45 (1999):143-166.

- Attribution

Public Domain This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Ligações externas[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Obras de Richard Whately (em inglês) no Projeto Gutenberg

- Introductory Lectures on Political Economy

For Whately the economist and for further links see: