Usuária:MCarrera (NeuroMat)/Testes/Braille

O Braille /breɪ|/ é um sistema de escrita tátil utilizado por pessoas cegas ou com baixa visão. É tradicionalmente escrito em papel em relevo. Os usuários do sistema Braille podem ler em telas de computadores e em outros suportes eletrônicos graças a displays em braille atualizáveis. Eles podem escrever em braille com reglete e punção, máquina de escrever em braille, notetaker em braille ou computadores que imprimem braille em relevo.

O Braille recebeu este nome devido ao seu criador Louis Braille, que perdeu a visão em um acidente na infância. Em 1884, Braille desenvolveu aos 15 anos um código para o alfabeto francês em uma melhoria para a escrita noturna. Em 1829, ele publicou o sistema, que posteriormente incluiria a notação musical.[1][2] Em 1837, ele publicou uma segunda revisão, que foi a primeira forma binária de escrita desenvolvida na era moderna. Os caracteres Braille eram pequenos blocos retangulares chamados de células, que contêm minúsculas protuberâncias palpáveis chamadas de pontos levantados. O número e a disposição destes pontos distinguem os caractere uns dos outros. Já que os vários alfabetos Braille originados como códigos de transcrição de sistemas de escrita impressa, os mapeamentos (conjuntos de designações de caracteres) variam de língua para língua.

Em inglês, o Braille tem três níveis de codificação:

Grau 1 – transcrição letra por letra para alfabetização básica;

Grau 2 – adição de abreviaturas e contrações;

Grau 3 – várias taquigrafias pessoais não padronizadas.

As células Braille não são os únicos elementos em um texto Braille. Pode haver ilustrações ou gráficos em relevo, com linhas sólidas ou feitas de séries de pontos, setas ou pontos maiores que os pontos Braille, entre outros.

Uma célula Braille completa inclui seis pontos levantados dispostos em duas linhas laterais, cada uma com três pontos.[3] As posições dos pontos são identificadas por números de um a seis.[3] São 64 soluções possíveis para usar um ou mais pontos.[3] Uma única célula pode ser usada para representar uma letra do alfabeto, um número, um sinal de pontuação ou mesmo uma palavra inteira.[3] Em face do software do leitor de tela, o uso do Braille tem diminuido. Entretanto, por ensinar ortografia e pontuação, a educação em Braille continua a ser importante para o desenvolvimento de habilidades de leitura entre crianças cegas ou com baixa visão (a alfabetização em Braille está relacionada com maior taxa de emprego).

História[editar | editar código-fonte]

O Braille foi baseado em um código militar tátil chamado de escrita noturna, desenvolvida por Charles Barbier em resposta ao pedido de Napoleon por um meio para os soldados se comunicarem silenciosamente à noite e sem uma fonte de luz.[4] No sistema de Barbier, conjuntos de 12 pontos em relevo codificavam 36 sons diferentes. Isto provou ser muito difícil para os soldados reconhecerem os códigos pelo toque, e foi rejeitado pelos militares.

Em 1821, Barbier visitou o Royal Institute for the Blind, em Paris, onde conheceu Louis Braille. Braille identificou dois defeitos principais no código. Primeiro, representando apenas sons, o código era incapaz de renderizar a ortografia das palavras. Segundo, o dedo humano não poderia englobar todo o símbolo de 12 pontos sem se mover e, portanto, não poderia se mover rapidamente de um símbolo para outro.

A solução de Braille foi usar células de 6 pontos e atribuir um padrão específico para cada letra do alfabeto.[5] Inicialmente, o Braille era uma transliteração um–para–um da ortografia francesa, mas logo várias abreviaturas, contrações e até mesmo logogramas foram desenvolvidos. Isto criou um sistema muito mais parecido com a taquigrafia.[6] O sistema inglês expandido chamado de Braille de grau 2 estava completo em 1905. Para leitores cegos, o Braille é um sistema de escrita independente, ao invés de um código de ortografia impressa.[7]

Derivação[editar | editar código-fonte]

O Braille é derivado do alfabeto latino, embora indiretamente. No sistema Braille original, os padrões de pontos foram atribuídos às letras de acordo com sua posição dentro da ordem alfabética do alfabeto francês, com letras acentuadas e w ordenada no final.[8] As dez primeiras letras do alfabeto (a – j) usam os quatro pontos superiores (observar os pontos pretos na tabela abaixo). Estes representam os dez dígitos (0 – 9) em um sistema paralelo à guemátria hebraica e à isopsefia grega. As células com menos pontos são atribuídas às três primeiras letras e aos dígitos mais baixos (abc = 123) e às três primeiras vogais nesta parte do alfabeto (aei), enquanto os dígitos par (4, 6, 8, 0) são ângulos retos. As dez letras seguintes (k – t) são idênticas às dez primeiras letras (a – j), respectivamente, com a adição de um ponto na posição três.

| a/1 | b/2 | c/3 | d/4 | e/5 | f/6 | g/7 | h/8 | i/9 | j/0 |

| k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t |

| u | v | x | y | z | w | ||||

As próximas dez letras (a próxima década) são as mesmas novamente, mas com pontos também nas posições 3 e 6 (pontos verdes). A letra w foi deixada de fora, porque não fazia parte do alfabeto francês enquanto Braille estava vivo. A ordem francesa em Braille é u v x y z ç é à è ù.[9]

As próximas dez letras (terminando em w) são as mesmas outra vez, exceto que a posição 6 (ponto roxo) é usada sem a posição 3. Estas são â ê î ô û ë ï ü ö w.[10]

A série a – j reduzida a um espaço de ponto é usada para pontuação. As letras a, b e c, que usam apenas pontos na linha superior, foram abaixadas dois lugares para o apóstrofo e o hífen.

Existem também dez padrões que se baseiam nas duas primeiras letras deslocadas para a direita. Estes foram atribuídos a letras não francesas (ì ä ò) ou tem outras funções como sobrescrito, letra maiúscula, sinal numérico, entre outros.

64 células Braille[a] Década Sequência numérica shift right 1

2

3

4

5 shiftdown

Havia originalmente nove décadas. Da quinta a nona década, eram usados tanto traços quanto pontos. Isto provou ser impraticável e foi abandonado logo. Estes poderiam ser substituídos com o que conhecemos como sinal do número, embora tenha valido apenas para os dígitos (5a década velha → 1a década moderna). O traço ocupando a linha superior da sexta década original foi simplesmente abandonado, produzindo a quinta década moderna.

Tarefa[editar | editar código-fonte]

Historicamente houve três princípios na atribuição dos valores de um script linear (impressão) para o Braille: usando os valores originais da letra francesa de Louis Braille, reatribuir as letras braille de acordo com a ordem de classificação do alfabeto de impressão que está sendo transcrito e reatribuir as letras para melhorar a eficiência da escrita em Braille.

Sob o consenso internacional, a maioria dos alfabetos Braille segue a ordem de classificação francesa para as 26 letras do alfabeto latino básico, e houve tentativas de unificar as letras além destas 26, embora as diferenças permaneçam. Por exemplo, em Braille alemão e as contrações em Braille Inglês. Esta unificação evita o caos de cada país reordenando o código Braile para corresponder à ordem de classificação do seu alfabeto de impressão, como aconteceu em Braille argelino, onde os códigos Braile foram numericamente reatribuídos para combinar com a ordem alfabética árabe e têm pouca relação com os valores usados em outros países (compare Braille moderno árabe, que usa a ordem de classificação francesa), e em uma versão americana recente do Braille inglês, onde as letras w, x, y, z foram reatribuídas para combinar com a ordem alfabética inglesa.

Uma convenção vista às vezes para além das 26 letras básicas é explorar a simetria física de padrões de Braille de forma icônica. Por exemplo, atribuindo um n invertido a ñ ou um s invertido a sh.

Um terceiro princípio era atribuir códigos de Braille de acordo com a freqüência, com os padrões mais simples (mais rápidos para escrever) atribuídos às letras mais frequentes do alfabeto. Estes alfabetos baseados em frequência foram usados na Alemanha e nos Estados Unidos no século XIX, mas nenhum é atestado no uso moderno. Finalmente existem scripts Braille que não ordenam os códigos numericamente como o Braille japonês e o Braille coreano, que se baseiam em princípios mais abstratos da composição da sílaba.

Os textos acadêmicos são às vezes escritos em um script de oito em vez de seis pontos por célula, permitindo-lhes codificar um maior número de símbolos. O Braille luxemburguês adotou células de oito pontos para uso geral. Por exemplo, adiciona um ponto abaixo de cada letra para derivar sua variante com letra maiúscula.

O código Braille[editar | editar código-fonte]

Cada célula braille possui 6 pontos de preenchimento, permitindo 63 combinações. Alguns consideram a célula vazia como um símbolo também, totalizando 64 combinações. Assim, podem-se designar combinações de pontos para todas as letras e para a pontuação da maioria dos alfabetos.

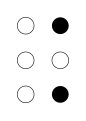

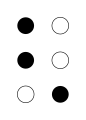

Cada ponto da célula recebe um número de identificação de 1 a 6, iniciando no primeiro ponto superior à esquerda, e terminando no último ponto inferior à direita, no sentido vertical.

O braille é lido da esquerda para a direita, com uma ou ambas as mãos. Vários idiomas usam uma forma abreviada de braille, na qual certas células são usadas no lugar de combinações de letras ou de palavras freqüentemente usadas. Algumas pessoas ganharam tanta prática em ler braille que conseguem ler até 200 palavras por minuto.

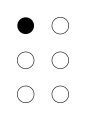

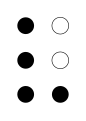

As primeiras dez letras (A a J) só usam os pontos das duas fileiras de cima. Os números de 1 a 9 e o zero são representados por esses mesmos dez sinais, precedidos pelo sinal de número, especial.

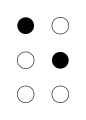

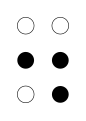

As dez letras seguintes (K a T) acrescentam o ponto no canto inferior esquerdo a cada uma das dez primeiras letras.

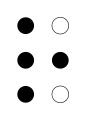

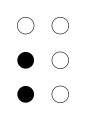

As últimas cinco letras (U a Z) acrescentam ambos os pontos inferiores às cinco primeiras letras, a exceção da letra "w", que foi acrescentada posteriormente ao alfabeto francês.

-

A, 1

-

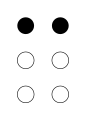

B, 2

-

C, 3

-

D, 4

-

E, 5

-

F, 6

-

G, 7

-

H, 8

-

I, 9

-

J, 0 (zero)

-

K

-

L

-

M

-

N

-

O

-

P

-

Q

-

R

-

S

-

T

-

U

-

V

-

W

-

X

-

Y

-

Z

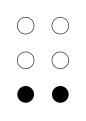

As combinações restantes, ainda possíveis visto que 63 hipóteses de combinação dos pontos, são usadas para pontuação, contrações e abreviaturas especiais.

-

Prefixo numérico

-

Ponto

-

Vírgula

-

Interrogação

-

Ponto e vírgula

-

Exclamação

-

Hífen

De acordo com a Grafia Braille Para a Língua Portuguesa (aprovada pela portaria nº 2.678 de 24 de setembro de 2002 [1]) e publicada pelo Ministério da Educação e Secretaria de Educação Especial (2ª edição, 2006), fazem-se necessárias as seguintes atualizações:

-

Maiúsculas. Se utilizado duas vezes seguidas, significa que a palavra toda é maiúscula. Para uma frase com mais de três palavras em "caixa alta", devemos iniciá-la com dois pontos (25), seguidos de dois sinais de maiúsculas e a última palavra da frase em questão deverá ser antecedida de dois sinais de maiúsculas novamente.

-

Apóstrofe

-

Aspas, tanto iniciais como finais.

Os parênteses foram subdivididos em cinco grupos:

-

Abertura (para números)

-

Fechamento (para números)

-

Abertura (para texto). São usadas 2 células

-

Fechamento (para texto). São usadas 2 células

Algumas contrações e abreviaturas às vezes tornam o braille difícil de aprender. Isto acontece especialmente no caso de pessoas que ficam cegas numa idade mais avançada, visto que a única forma de aprender braile é memorizar todos os sinais. Por esse motivo, há vários "graus" de braille.

O braille por extenso, ou grau um, só utiliza os sinais que representam o alfabeto e a pontuação, os números e alguns poucos sinais especiais de composição que são especifíos do sistema. Corresponde letra por letra, à impressão visual que é observável num texto comum. Este grau é o mais fácil de se aprender, visto que há menos sinais para memorizar. Por outro lado, o braille grau um é o mais lento para ser transcrito e lido, e o produto final, impresso, é mais volumoso. Visto que a maioria do braille produzido hoje é transcrito e produzido por voluntários, em organizações não lucrativas, o grau um é usado raramente.

O braille grau dois é uma forma mais abreviada do braille. Por exemplo, em inglês, cada um dos 26 sinais que representam o alfabeto têm um significado duplo. Se o sinal é usado em combinação com outros padrões dentro de uma palavra, representa apenas uma letra, mas se estiver isolado representa uma palavra comum. Isto ocorre similarmente no braille português. Assim, por exemplo, o sinal para n isolado representa não, abx representa abaixo, abt, absoluto, ag, alguém, e assim por diante. Outros sinais são empregues para representar prefixos e sufixos comuns. O uso de contracções e abreviaturas reduz bastante o tempo envolvido em transcrever e ler a matéria, bem como o tamanho do volume acabado. Actualmente, portanto, este é o grau mais comum do braille. Em contrapartida, é mais difícil aprender o braille abreviado grau dois. É necessário memorizar todos os 63 sinais diferentes (a maioria dos quais tem mais de um significado, dependendo de como são usados), mas também é preciso aprender o conjunto de regras necessárias que governam quando cada sinal pode ou não ser usado.

O grau três é uma forma de braille altamente abreviada, especialmente usada em inglês. No grau três há várias contracções e abreviaturas a memorizar, e as regras que governam o seu uso são correspondentemente difíceis. O braille grau três é usualmente utilizado em anotações científicas ou em outras matérias muito técnicas. Visto que bem poucos cegos conseguem ler este grau de braille, não é usado com frequência.

Alfabeto Braille com codificação Unicode[editar | editar código-fonte]

| Padrões básicos | ⠁ | ⠃ | ⠉ | ⠙ | ⠑ | ⠋ | ⠛ | ⠓ | ⠊ | ⠚ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letra | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J |

| Número | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 |

| Com o ponto 3 | ⠅ | ⠇ | ⠍ | ⠝ | ⠕ | ⠏ | ⠟ | ⠗ | ⠎ | ⠞ |

| Letra | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T |

| Com os pontos 3 e 6 | ⠥ | ⠧ | ⠭ | ⠽ | ⠵ | ⠯ | ⠿ | ⠷ | ⠮ | ⠾ |

| Letra | U | V | X | Y | Z | Ç | É | Á | È | Ú |

| Com o ponto 6 | ⠡ | ⠣ | ⠩ | ⠹ | ⠱ | ⠫ | ⠻ | ⠳ | ⠪ | ⠺ |

| Letra | Â | Ê | Ì | Ô | Ù | À | Ï | Ü | Õ | Ò/W |

Outros padrões e combinações:

| Braille | Letra/Símbolo |

|---|---|

| ⠌ | Í |

| ⠜ | Ã |

| ⠬ | Ó |

| ⠂ | vírgula (,) |

| ⠄ | ponto (.) / apóstrofo (') |

| ⠄⠄⠄ | reticências (…) |

| ⠆ | ponto-e-vírgula (;) |

| ⠒ | dois-pontos (:) |

| ⠖ | ponto de exclamação (!) |

| ⠢ | ponto de interrogação (?) |

| ⠤ | hífen (–) |

| ⠤⠤ | travessão (—) |

| ⠦ | aspas (") |

| ⠣⠄ | abre parêntese [(] (para texto) |

| ⠠⠜ | fecha parêntese [)] (para texto) |

| ⠣ | abre parêntese [(] (para números) |

| ⠜ | fecha parêntese [)] (para números) |

| ⠔ | asterisco (*) |

| ⠰ | cifrão ($) |

| ⠈⠑ | euro (€) |

| ⠔ | grifo (exemplo) |

| ⠨ | inicial maiúscula (Exemplo) |

| ⠨⠨ | caixa alta (EXEMPLO) |

| ⠼ | número |

Mídia Braille[editar | editar código-fonte]

A impressão em Braille não é utilizada somente em livros e folhetos. Ultimamente ela vem sendo utilizada em cds, dvds e blue ray como uma nova forma de leitura. São fabricados com impressões em braile no rótulo da mídia para que haja facilidade na identificação do conteúdo.[11]

Form[editar | editar código-fonte]

Braille was the first writing system with binary encoding.[6] The system as devised by Braille consists of two parts:[7]

- Character encoding that mapped characters of the French alphabet to tuples of six bits (the dots),

- The physical representation of those six-bit characters with raised dots in a braille cell.

Within an individual cell, the dot positions are arranged as two columns of three positions. A raised dot can appear in any of the six positions, producing sixty-four (26) possible patterns, including one in which there are no raised dots. For reference purposes, a pattern is commonly described by listing the positions where dots are raised, the positions being universally numbered, from top to bottom, as 1 to 3 on the left and 4 to 6 on the right. For example, dot pattern 1-3-4 describe a cell with three dots raised, at the top and bottom in the left column and at the top of the right column: that is, the letter Predefinição:Braille cell m. The lines of horizontal braille text are separated by a space, much like visible printed text, so that the dots of one line can be differentiated from the braille text above and below. Different assignments of braille codes (or code pages) are used to map the character sets of different printed scripts to the six-bit cells. Braille assignments have also been created for mathematical and musical notation. However, because the six-dot braille cell allows only 64 (26) patterns, including the space, the characters of a braille script commonly have multiple values, depending on their context. That is, character mapping between print and braille is not one-to-one. For example, the character Predefinição:Bc corresponds in print to both the letter d and the digit 4.

In addition to simple encoding, many braille alphabets use contractions to reduce the size of braille texts and to increase reading speed. (See Contracted braille)

Writing braille[editar | editar código-fonte]

Braille may be produced by hand using a slate and stylus in which each dot is created from the back of the page, writing in mirror image, or it may be produced on a braille typewriter or Perkins Brailler, or an electronic Brailler or eBrailler. Because braille letters cannot be effectively erased and written over if an error is made, an error is overwritten with all six dots (Predefinição:Bc). Interpoint refers to braille printing that is offset, so that the paper can be embossed on both sides, with the dots on one side appearing between the divots that form the dots on the other (see the photo in the box at the top of this article for an example). Using a computer or other electronic device, braille may be produced with a braille embosser (printer) or a refreshable braille display (screen).

Braille has been extended to an 8-dot code, particularly for use with braille embossers and refreshable braille displays. In 8-dot braille the additional dots are added at the bottom of the cell, giving a matrix 4 dots high by 2 dots wide. The additional dots are given the numbers 7 (for the lower-left dot) and 8 (for the lower-right dot). Eight-dot braille has the advantages that the case of an individual letter is directly coded in the cell containing the letter and that all the printable ASCII characters can be represented in a single cell. All 256 (28) possible combinations of 8 dots are encoded by the Unicode standard. Braille with six dots is frequently stored as Braille ASCII.

Letters[editar | editar código-fonte]

The first 25 braille letters, up through the first half of the 3rd decade, transcribe a–z (skipping w). In English Braille, the rest of that decade is rounded out with the ligatures and, for, of, the, and with. Omitting dot 3 from these forms the 4th decade, the ligatures ch, gh, sh, th, wh, ed, er, ou, ow and the letter w.

| Predefinição:Braille cell | Predefinição:Braille cell | Predefinição:Braille cell |

| ch | sh | th |

(See English Braille.)

Formatting[editar | editar código-fonte]

Various formatting marks affect the values of the letters that follow them. They have no direct equivalent in print. The most important in English Braille are:

| Predefinição:Braille cell | Predefinição:Braille cell |

| Capital follows |

Number follows |

That is, Predefinição:Braille cell is read as capital 'A', and Predefinição:Braille cell as the digit '1'.

Punctuation[editar | editar código-fonte]

Basic punctuation marks in English Braille include:

Predefinição:Braille cell is both the question mark and the opening quotation mark. Its reading depends on whether it occurs before a word or after.

Predefinição:Braille cell is used for both opening and closing parentheses. Its placement relative to spaces and other characters determines its interpretation.

Punctuation varies from language to language. For example, French Braille uses Predefinição:Braille cell for its question mark and swaps the quotation marks and parentheses (to Predefinição:Braille cell and Predefinição:Braille cell); it uses the period (Predefinição:Braille cell) for the decimal point, as in print, and the decimal point (Predefinição:Braille cell) to mark capitalization.

Contractions[editar | editar código-fonte]

Braille contractions are words and affixes that are shortened so that they take up fewer cells. In English Braille, for example, the word afternoon is written with just three letters, Predefinição:Bc ⟨afn⟩, much like stenoscript. There are also several abbreviation marks that create what are effectively logograms.[7] The most common of these is dot 5, which combines with the first letter of words. With the letter Predefinição:Bc m, the resulting word is Predefinição:Bc mother. There are also ligatures ("contracted" letters), which are single letters in braille but correspond to more than one letter in print. The letter Predefinição:Bc and, for example, is used to write words with the sequence a-n-d in them, such as Predefinição:Bc hand.

| Predefinição:Braille cell | Predefinição:Braille cell | Predefinição:Braille cell |

| afternoon (a-f-n) |

mother (dot 5-m) |

hand (h-and) |

Page dimensions[editar | editar código-fonte]

Most braille embossers support between 34 and 40 cells per line, and 25 lines per page.

A manually operated Perkins braille typewriter supports a maximum of 42 cells per line (its margins are adjustable), and typical paper allows 25 lines per page.

A large interlining Stainsby has 36 cells per line and 18 lines per page.

An A4-sized Marburg braille frame, which allows interpoint braille (dots on both sides of the page, offset so they do not interfere with each other) has 30 cells per line and 27 lines per page.

Literacy[editar | editar código-fonte]

A sighted child who is reading at a basic level should be able to understand common words and answer simple questions about the information presented.[12] The child should also have enough fluency to get through the material in a timely manner. Over the course of a child's education, these foundations are built upon to teach higher levels of math, science, and comprehension skills.[12]

Children who are blind not only have the education disadvantage of not being able to see — they also miss out on fundamental parts of early and advanced education if not provided with the necessary tools. Children who are blind or visually impaired can begin learning pre-braille skills from a very young age to become fluent braille readers as they get older.

U.S. braille literacy statistics[editar | editar código-fonte]

In 1960, 50% of legally blind, school-age children were able to read braille in the U.S.[13][14] According to the 2015 Annual Report from the American Printing House for the Blind, there were 61,739 legally blind students registered in the U.S. Of these, 8.6% (5,333) were registered as braille readers, 31% (19,109) as visual readers, 9.4% (5,795) as auditory readers, 17% (10,470) as pre-readers, and 34% (21,032) as non-readers.[15]

There are numerous causes for the decline in braille usage, including school budget constraints, technology advancement, and different philosophical views over how blind children should be educated.[16]

A key turning point for braille literacy was the passage of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, an act of Congress that moved thousands of children from specialized schools for the blind into mainstream public schools.[14] Because only a small percentage of public schools could afford to train and hire braille-qualified teachers, braille literacy has declined since the law took effect.[necessário esclarecer][14] Braille literacy rates have improved slightly since the bill was passed,[necessário esclarecer] in part because of pressure from consumers and advocacy groups that has led 27 states to pass legislation mandating that children who are legally blind be given the opportunity to learn braille.[16]

In 1998 there were 57,425 legally blind students registered in the United States, but only 10% (5,461) of them used braille as their primary reading medium.[17][18]

Early braille education is crucial to literacy for a blind or low-vision child. A study conducted in the state of Washington found that people who learned braille at an early age did just as well, if not better, than their sighted peers in several areas, including vocabulary and comprehension. In the preliminary adult study, while evaluating the correlation between adult literacy skills and employment, it was found that 44% of the participants who had learned to read in braille were unemployed, compared to the 77% unemployment rate of those who had learned to read using print.[19] Currently, among the estimated 85,000 blind adults in the United States, 90% of those who are braille-literate are employed. Among adults who do not know braille, only 33% are employed.[14] Statistically, history has proven that braille reading proficiency provides an essential skill set that allows blind or low-vision children to compete with their sighted peers in a school environment and later in life as they enter the workforce.[16]

United Kingdom[editar | editar código-fonte]

Though braille is thought to be the main way blind people read and write, in Britain (for example) out of the reported 2 million blind and low vision population, it is estimated that only around 15–20 thousand people use braille.[20] Younger people are turning to electronic text on computers with screen reader software instead, a more portable communication method that they can use with their friends. A debate has started on how to make braille more attractive and for more teachers to be available to teach it.

Braille transcription[editar | editar código-fonte]

Although it is possible to transcribe print by simply substituting the equivalent braille character for its printed equivalent, in English such a character-by-character transcription (known as uncontracted braille) is only used by beginners.

Braille characters are much larger than their printed equivalents, and the standard 11" by 11.5" (28 cm × 30 cm) page has room for only 25 lines of 43 characters. To reduce space and increase reading speed, most braille alphabets and orthographies use ligatures, abbreviations, and contractions. Virtually all English Braille books are transcribed in this contracted braille, which adds an additional layer of complexity to English orthography: The Library of Congress's Instruction Manual for Braille Transcribing[21] runs to over 300 pages and braille transcribers must pass certification tests.

Fully contracted braille is known as Grade 2 Braille. There is an intermediate form between Computer Braille—one-for-one identity with print—and Grade 2, which is called Grade 1 Braille. In Grade 1 the capital-sign and Number sign are used, and most punctuation marks are shown using their Grade 2 values.

The system of contractions in English Braille begins with a set of 23 words which are contracted to single characters. Thus the word but is contracted to the single letter b, can to c, do to d, and so on. Even this simple rule creates issues requiring special cases; for example, d is, specifically, an abbreviation of the verb do; the noun do representing the note of the musical scale is a different word, and must be spelled out.

Portions of words may be contracted, and many rules govern this process. For example, the character with dots 2-3-5 (the letter "f" lowered in the braille cell) stands for "ff" when used in the middle of a word. At the beginning of a word, this same character stands for the word "to"; the character is written in braille with no space following it. (This contraction was removed in the Unified English Braille Code.) At the end of a word, the same character represents an exclamation point.

Some contractions are more similar than their print equivalents. For example, the contraction ⟨lr⟩, meaning 'letter', differs from ⟨ll⟩, meaning 'little', only in adding one dot to the second ⟨l⟩: Predefinição:Bc little, Predefinição:Bc letter. This causes greater confusion between the braille spellings of these words and can hinder the learning process of contracted braille.[22]

The contraction rules take into account the linguistic structure of the word; thus, contractions are generally not to be used when their use would alter the usual braille form of a base word to which a prefix or suffix has been added. Some portions of the transcription rules are not fully codified and rely on the judgment of the transcriber. Thus, when the contraction rules permit the same word in more than one way, preference is given to "the contraction that more nearly approximates correct pronunciation."

Grade 3 Braille[23] is a variety of non-standardized systems that include many additional shorthand-like contraction. They are not used for publication, but by individuals for their personal convenience.

Braille translation software[editar | editar código-fonte]

When people produce braille, this is called braille transcription. When computer software produces braille, this is called braille translation. Braille translation software exists to handle most of the common languages of the world, and many technical areas, such as mathematics (mathematical notation), for example WIMATS, music (musical notation), and tactile graphics.

Braille-reading techniques[editar | editar código-fonte]

Since braille is one of the few writing systems where tactile perception is used, as opposed to visual perception, a braille reader must develop new skills. One skill important for braille readers is the ability to create smooth and even pressures when running one's fingers along the words. There are many different styles and techniques used for the understanding and development of braille, even though a study by B. F. Holland[24] suggests that there is no specific technique that is superior to any other.

Another study by Lowenfield & Abel[25] shows that braille could be read "the fastest and best... by students who read using the index fingers of both hands." Another important reading skill emphasized in this study is to finish reading the end of a line with the right hand and to find the beginning of the next line with the left hand simultaneously. One final conclusion drawn by both Lowenfield and Abel is that children have difficulty using both hands independently where the right hand is the dominant hand. But this hand preference does not correlate to other activities.

International uniformity[editar | editar código-fonte]

When braille was first adapted to languages other than French, many schemes were adopted, including mapping the native alphabet to the alphabetical order of French – e.g. in English W, which was not in the French alphabet at the time, is mapped to braille X, X to Y, Y to Z, and Z to the first French accented letter – or completely rearranging the alphabet such that common letters are represented by the simplest braille patterns. Consequently, mutual intelligibility was greatly hindered by this state of affairs. In 1878, the International Congress on Work for the Blind, held in Paris, proposed an international braille standard, where braille codes for different languages and scripts would be based, not on the order of a particular alphabet, but on phonetic correspondence and transliteration to Latin.[26]

This unified braille has been applied to the languages of India and Africa, Arabic, Vietnamese, Hebrew, Russian, and Armenian, as well as nearly all Latin-script languages. Greek, for example, gamma is written as Latin g, despite the fact that it has the alphabetic position of c; Hebrew bet, the second letter of the alphabet and cognate with the Latin letter b, is sometimes pronounced /b/ and sometimes /v/, and is written b or v accordingly; Russian ts is written as c, which is the usual letter for /ts/ in those Slavic languages that use the Latin alphabet; and Arabic f is written as f, despite being historically p, and occurring in that part of the Arabic alphabet (between historic o and q).

Other braille conventions[editar | editar código-fonte]

Other systems for assigning values to braille patterns are also followed, beside the simple mapping of the alphabetical order onto the original French order. Some braille alphabets start with unified braille, and then diverge significantly based on the phonology of the target languages, while others diverge even further.

In the various Chinese systems, traditional braille values are used for initial consonants and the simple vowels. In both Mandarin and Cantonese Braille, however, characters have different readings depending on whether they are placed in syllable-initial (onset) or syllable-final (rime) position. For instance, the cell for Latin k, Predefinição:Braille cell, represents Cantonese k (g in Yale and other modern romanizations) when initial, but aak when final, while Latin j, Predefinição:Braille cell, represents Cantonese initial j but final oei.

Novel systems of braille mapping include Korean, which adopts separate syllable-initial and syllable-final forms for its consonants, explicitly grouping braille cells into syllabic groups in the same way as hangul. Japanese, meanwhile, combines independent vowel dot patterns and modifier consonant dot patterns into a single braille cell – an abugida representation of each Japanese mora.

Uses[editar | editar código-fonte]

The current series of Canadian banknotes has a tactile feature consisting of raised dots that indicate the denomination, allowing bills to be easily identified by blind or low vision people. It does not use standard braille; rather, the feature uses a system developed in consultation with blind and low vision Canadians after research indicated that braille was not sufficiently robust and that not all potential users read braille. Mexican bank notes, Indian rupee notes, Israeli New Shekel notes,[27] Russian Ruble and Swiss Franc notes also have special raised symbols to make them identifiable by persons who are blind or low vision. {{carece de fontes}}

In India there are instances where the parliament acts have been published in braille, such as The Right to Information Act.[28]

In the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990[29] requires various building signage to be in braille.

In the United Kingdom, it is required that medicines have the name of the medicine in Braille on the labelling.[30]

Australia also recently introduced the tactile feature onto their five dollar banknote[31]

Unicode[editar | editar código-fonte]

Braille was added to the Unicode Standard in September, 1999 with the release of version 3.0.

Most braille embossers and refreshable braille displays do not support Unicode, using instead 6-dot braille ASCII. Some embossers have proprietary control codes for 8-dot braille or for full graphics mode, where dots may be placed anywhere on the page without leaving any space between braille cells, so that continuous lines can be drawn in diagrams, but these are rarely used and are not standard.

The Unicode standard encodes 8-dot braille glyphs according to their binary appearance, rather than following their assigned numeric order. Dot 1 corresponds to the least significant bit of the low byte of the Unicode scalar value, and dot 8 to the high bit of that byte.

The Unicode block for braille is U+2800 ... U+28FF:

Predefinição:Unicode chart Braille Patterns

Observation[editar | editar código-fonte]

Every year on the 4th of January, World Braille Day is observed internationally to commemorate the birth of Louis Braille and to recognize his efforts. However, the event is not considered a public holiday.[32]

Ver também[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Accessible publishing

- Braille literacy

- Braille music

- Braille technology

- Braille translator

- Braille watch

- English Braille

- List of binary codes

- List of international common standards

- Moon type

- Needle punch

- Nemeth Braille (for math)

- Refreshable Braille display

- Tactile alphabets for the blind

- Tactile graphic

- Tangible symbol systems

- Unified English Braille

Notas[editar | editar código-fonte]

Referências

- ↑ Louis Braille, 1829, Method of Writing Words, Music, and Plain Songs by Means of Dots, for Use by the Blind and Arranged for Them

- ↑ «How Braille began». http://www.brailler.com

- ↑ a b c d «The dot positions are identified by numbers from one through six». AFB.org. Consultado em June 19, 2016 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ «What is Braille». http://www.afb.org

- ↑ Roy, Noëlle, «Louis Braille 1809–1852, a French genius» (PDF), Valentin Haüy Association website, consultado em 5 de fevereiro de 2011

- ↑ a b Peter Daniels, 1996, "Analog and Digital Writing", in The World's Writing Systems, p 886

- ↑ a b c Daniels & Bright, 1996, The World's Writing Systems, p 817–818

- ↑ Madeleine Loomis, 1942, The Braille Reference Book [for Grades I, I½, and II].

- ↑ The values of the letters after z differ from language to language; these are Braille's assignments for French.

- ↑ W had been tacked onto the 39 letters of the French alphabet to accommodate English.

- ↑ CD Agora. «Mídia Braille». Sayuri Matsuo. Consultado em 18 de novembro de 2014

- ↑ a b Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Research: Evidence Based Education Science and the Challenge of Learning to Read, consultado em 20 de abril de 2009

- ↑ American Foundation for the Blind: Programs and Policy Research, «Estimated Number of Adult Braille Readers in the United States», International Braille Research Center (IBRC), consultado em 15 de abril de 2009

- ↑ a b c d Ranalli, Ralph (5 de janeiro de 2008), «A Boost for Braille», The Boston Globe, consultado em 17 de abril de 2009

- ↑ American Printing House for the Blind (2016), Annual Report 2015 (PDF), consultado em 27 de outubro de 2016

- ↑ a b c Riles, Ruby, «The Impact of Braille Reading Skills on Employment, Income, Education, and Reading Habits», Braille Research Center, consultado em 15 de abril de 2009

- ↑ American Printing House for the Blind (APH) (1999), APH maintains an annual register of legally blind students below the college level, consultado em 27 de outubro de 2016, Arquivado do original em 31 January 2002 Verifique data em:

|arquivodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Ebnet, Matthew (30 de junho de 2001), «Braille Challenge Gives Young Blind Students a Chance to Shine», The Los Angeles Times, consultado em 15 de abril de 2009

- ↑ Riles Ph.D., Ruby (2004), «Research Study: Early Braille Education Vital», Future Reflections, consultado em 15 de abril de 2009

- ↑ Damon Rose (2012). «Braille is spreading but who's using it?». bbc.co.uk. Consultado em 14 October 2013 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Risjord, Constance (2009). Instruction Manual for Braille Transcribing, Library of Congress, 5th ed. ISBN 0-8444-1227-9

- ↑ Hampshire, Barry. Working with Braille. Paris: Unesco, 1981.

- ↑ Grade 3 Braille. geocities.com (June 2000). Retrieved on 2012-12-21.

- ↑ B.F. Holland, 'Speed and Pressure Factors in Braille Reading', Teachers Forum, Vol. 7, September 1934 pp. 13–17

- ↑ B. Lowenfield and G. L. Abel, Methods of Teaching Braille Reading Efficiency of Children in Lower Senior Classes. Birmingham, Research Centre for the Education of the Visually Handicapped, 1977

- ↑ «International Meeting on Braille Uniformity» (PDF). UNESCO. Consultado em 24 de abril de 2012

- ↑ Bank of Israel – Banknote Security Features – Raised print (intaglio). boi.org.il. Retrieved on 2013-01-11.

- ↑ National : Right to Information Act in Braille. The Hindu (2006-07-04). Retrieved on 2012-12-21.

- ↑ ada.gov. ada.gov. Retrieved on 2012-12-21.

- ↑ Medicines: packaging, labelling and patient information leaflets. gov.uk. Retrieved on 2015-05-05.

- ↑ «Finally, Australian currency will be accessible to the blind». 31 August 2016 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ «World Braille Day : 4th January». www.calendarlabs.com. Consultado em 2 January 2017 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda)

Ligações externas[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Curso Virtual gratuito de Braille - Universidade de São Paulo

- Associação Sorocabana de Atividades para Deficientes Visuais

- Delius - Conversor gratuito de partituras musicais para Braille, descrito na tese Uma ferramenta para notação musical em Braille, de Arthur Tofani

- Grafia Braille para a Língua Portuguesa - Ministério da Educação - Secretaria de Educação Especial

- Sinalização Tátil - Placas em Braille - Total Acessibilidade

- en:Portuguese Braille

Categoria:Louis Braille

Categoria:Sistemas de escrita

Categoria:Cegueira

Categoria:Codificação

Categoria:1825 na ciência

Categoria:Tipografia digital

Categoria:Epônimos

Categoria:Invenções da França

Categoria:Invenções do século XIX

Erro de citação: Existem etiquetas <ref> para um grupo chamado "lower-alpha", mas não foi encontrada nenhuma etiqueta <references group="lower-alpha"/> correspondente