Usuário:Burmeister/Sandbox

Protists (![]() /ˈproʊt

/ˈproʊtɪst/) are a diverse group of eukaryotic microorganisms. Historically, protists were treated as the kingdom Protista, which includes mostly unicellular organisms that do not fit into the other kingdoms, but this group is contested in modern taxonomy.[1] Instead, it is "better regarded as a loose grouping of 30 or 40 disparate phyla with diverse combinations of trophic modes, mechanisms of motility, cell coverings and life cycles."[2]

The protists do not have much in common besides a relatively simple organization[3]—either they are unicellular, or they are multicellular without specialized tissues. This simple cellular organization distinguishes the protists from other eukaryotes, such as fungi, animals and plants.

The term protista was first used by Ernst Haeckel in 1866. Protists were traditionally subdivided into several groups based on similarities to the "higher" kingdoms: the unicellular "animal-like" protozoa, the "plant-like" protophyta (mostly unicellular algae), and the "fungus-like" slime molds and water molds. These traditional subdivisions, largely based on superficial commonalities, have been replaced by classifications based on phylogenetics (evolutionary relatedness among organisms). However, the older terms are still used as informal names to describe the morphology and ecology of various protists.

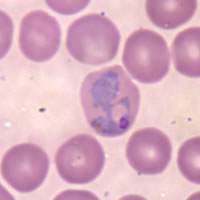

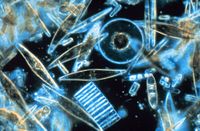

Protists live in almost any environment that contains liquid water. Many protists, such as the algae, are photosynthetic and are vital primary producers in ecosystems, particularly in the ocean as part of the plankton. Other protists, such as the Kinetoplastids and Apicomplexa, are responsible for a range of serious human diseases, such as malaria and sleeping sickness.

Classification[editar | editar código-fonte]

Historical classifications[editar | editar código-fonte]

The first division of the protists from other organisms came in the 1830s, when the German biologist Georg August Goldfuss introduced the word protozoa to refer to organisms such as ciliates and corals.[4] This group was expanded in 1845 to include all "unicellular animals", such as Foraminifera and amoebae. The formal taxonomic category Protoctista was first proposed in the early 1860s by John Hogg, who argued that the protists should include what he saw as primitive unicellular forms of both plants and animals. He defined the Protoctista as a "fourth kingdom of nature", in addition to the then-traditional kingdoms of plants, animals and minerals.[4] The kingdom of minerals was later removed from taxonomy by Ernst Haeckel, leaving plants, animals, and the protists as a “kingdom of primitive forms”.[5]

Herbert Copeland resurrected Hogg's label almost a century later, arguing that "Protoctista" literally meant "first established beings", Copeland complained that Haeckel's term protista included anucleated microbes such as bacteria. Copeland's use of the term protoctista did not. In contrast, Copeland's term included nucleated eukaryotes such as diatoms, green algae and fungi.[6] This classification was the basis for Whittaker's later definition of Fungi, Animalia, Plantae and Protista as the four kingdoms of life.[7] The kingdom Protista was later modified to separate prokaryotes into the separate kingdom of Monera, leaving the protists as a group of eukaryotic microorganisms.[8] These five kingdoms remained the accepted classification until the development of molecular phylogenetics in the late 20th century, when it became apparent that neither protists nor monera were single groups of related organisms (they were not monophyletic groups).[9]

Modern classifications[editar | editar código-fonte]

Currently, the term protist is used to refer to unicellular eukaryotes that either exist as independent cells, or if they occur in colonies, do not show differentiation into tissues.[10] The term protozoa is used to refer to heterotrophic species of protists that do not form filaments. These terms are not used in current taxonomy, and are retained only as convenient ways to refer to these organisms.

The taxonomy of protists is still changing. Newer classifications attempt to present monophyletic groups based on ultrastructure, biochemistry, and genetics. Because the protists as a whole are paraphyletic, such systems often split up or abandon the kingdom, instead treating the protist groups as separate lines of eukaryotes. The recent scheme by Adl et al. (2005)[10] is an example that does not bother with formal ranks (phylum, class, etc.) and instead lists organisms in hierarchical lists. This is intended to make the classification more stable in the long term and easier to update. Some of the main groups of protists, which may be treated as phyla, are listed in the taxobox at right.[11] Many are thought to be monophyletic, though there is still uncertainty. For instance, the excavates are probably not monophyletic and the chromalveolates are probably only monophyletic if the haptophytes and cryptomonads are excluded.[12]

Metabolism[editar | editar código-fonte]

Nutrition in some different types of protists is variable. In flagellates, for example, filter feeding may sometimes occur where the flagella find the prey. Other protists can engulf bacteria and digest them internally, by extending their cell membrane around the food material to form a food vacuole. This is then taken into the cell via endocytosis (usually phagocytosis; sometimes pinocytosis).

| Nutritional type | Source of energy | Source of carbon | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phototrophs | Sunlight | Organic compounds or carbon fixation | Algae, Dinoflagellates or Euglena |

| Organotrophs | Organic compounds | Organic compounds | Apicomplexa, Trypanosomes or Amoebae |

Reproduction[editar | editar código-fonte]

Some protists reproduce sexually (gametes), while others reproduce asexually (binary fission).

Some species, for example Plasmodium falciparum, have extremely complex life cycles that involve multiple forms of the organism, some of which reproduce sexually and others asexually.[13] However, it is unclear how frequently sexual reproduction causes genetic exchange between different strains of Plasmodium in nature and most populations of parasitic protists may be clonal lines that rarely exchange genes with other members of their species.[14]

Role as pathogens[editar | editar código-fonte]

Some protists are significant pathogens of both animals and plants; for example Plasmodium falciparum, which causes malaria in humans, and Phytophthora infestans, which causes late blight in potatoes.[15] A more thorough understanding of protist biology may allow these diseases to be treated more efficiently.

Researchers from the Agricultural Research Service are taking advantage of protists as pathogens in an effort to control red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) populations in Argentina. With the help of spore-producing protists such as Kneallhazia solenopsae the red fire ant populations can be reduced by 53-100%.[16] Researchers have also found a way to infect phorid flies with the protist without harming the flies. This is important because the flies act as a vector to infect the red fire ant population with the pathogenic protist.[17]

References[editar | editar código-fonte]

- ↑ Simonite T (2005). «Protists push animals aside in rule revamp». Nature. 438 (7064): 8–9. PMID 16267517. doi:10.1038/438008b

- ↑ Harper, David; Benton, Michael (2009). Introduction to Paleobiology and the Fossil Record. [S.l.]: Wiley-Blackwell. 207 páginas. ISBN 1-4051-4157-3

- ↑ «Systematics of the Eukaryota». Consultado em 31 de maio de 2009

- ↑ a b Scamardella, J. M. (1999). «Not plants or animals: a brief history of the origin of Kingdoms Protozoa, Protista and Protoctista» (PDF). International Microbiology. 2: 207–221

- ↑ Rothschild LJ (1989). «Protozoa, Protista, Protoctista: what's in a name?» (PDF). J Hist Biol. 22 (2): 277–305. PMID 11542176. doi:10.1007/BF00139515

- ↑ Copeland, H. F. (1938). «The Kingdoms of Organisms». Quarterly Review of Biology. 13 (4). 383 páginas. JSTOR 2808554. doi:10.1086/394568

- ↑ Whittaker, R. H. (1959). «On the Broad Classification of Organisms». Quarterly Review of Biology. 34 (3). 210 páginas. JSTOR 2816520. doi:10.1086/402733

- ↑ Whittaker RH (1969). «New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms». Science. 163 (3863): 150–60. PMID 5762760. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150

- ↑ Stechmann, Alexandra; Thomas Cavalier-Smith (2003). «The root of the eukaryote tree pinpointed» (PDF). Current Biology. 13: R665-R666. PMID 12956967. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00602-X. Consultado em 15 May 2011 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ a b Adl SM, Simpson AG, Farmer MA; et al. (2005). «The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists». J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 52 (5): 399–451. PMID 16248873. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x

- ↑ Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE (2003). «Phylogeny and classification of phylum Cercozoa (Protozoa)». Protist. 154 (3-4): 341–58. PMID 14658494. doi:10.1078/143446103322454112

- ↑ Laura Wegener Parfrey, Erika Barbero, Elyse Lasser, Micah Dunthorn, Debashish Bhattacharya, David J Patterson, and Laura A Katz (2006 December). «Evaluating Support for the Current Classification of Eukaryotic Diversity». PLoS Genet. 2 (12): e220. PMC 1713255

. PMID 17194223. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020220 Verifique data em:

. PMID 17194223. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020220 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Talman AM, Domarle O, McKenzie FE, Ariey F, Robert V (2004). «Gametocytogenesis: the puberty of Plasmodium falciparum». Malar. J. 3. 24 páginas. PMC 497046

. PMID 15253774. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-3-24

. PMID 15253774. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-3-24

- ↑ Tibayrenc M, Kjellberg F, Arnaud J; et al. (1991). «Are eukaryotic microorganisms clonal or sexual? A population genetics vantage». Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 (12): 5129–33. PMC 51825

. PMID 1675793. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.12.5129

. PMID 1675793. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.12.5129

- ↑ N. Campbell, J. Reese. Biology. 2008. pp. 583, 588

- ↑ «ARS Parasite Collections Assist Research and Diagnoses». USDA Agricultural Research Service. January 28, 2010 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ [1]

External links[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Tree of Life: Eukaryotes

- A java applet for exploring the new higher level classification of eukaryotes

- Plankton Chronicles - Protists - Cells in the Sea - video

Filo Plasmodroma[editar | editar código-fonte]

Classe 1. Mastigophora[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 1. Phytomastigina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1: Chrisomonadina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 2: Cryptomonadina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Da uma olhada aqui Elyvelton libero

Ordem 3: Phytomonadina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 4: Euglenoidina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 5: Chloromonadina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 6: Dinoflagellata[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 2. Zoomastigina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1: Choanoflagellina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 2: Rhizomastigina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 3: Protomonadina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 4: Retortamonadina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 5: Diplomonadina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 6: Oxymonadina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 7: Trichomonadina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 8: Hypermastigina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Classe 2. Opalinata[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1. Opalinida[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Principais representantes: Opalina, Cepedia.

Classe 3. Sarcodina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 1 Rhizopoda[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1. Amoebina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 2. Testacea[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 3. Gromiina[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 4. Foraminífera[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 5. Mycetozoa[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 6. Labyrinthulina Igor Cardoso[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 2. Piroplasmea[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1. Piroplasmida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 3. Actinopoda[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1. Radiolaria[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 2. Acantharia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 3. Heliozoa[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 4. Proteomyxa[editar | editar código-fonte]

Classe 4. Sporozoa[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 1. Telosporidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1. Gregarinida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 2. Coccidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 3. Haemosporidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 2. Acnidosporidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1. Haplosporidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 2. Sarcosporidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 3. Cnidosporidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1. Myxosporidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 2. Actinomyxidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 3. Microsporidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 4. Helicosporidia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Filo B. Ciliophora[editar | editar código-fonte]

- O Filo Ciliophora contém apenas a Classe Ciliata mas esta se divide em duas Subclasses: Holotricha e Spirotricha.

Classe Ciliata[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 1 Holotricha[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1: Gymnostomatida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 2: Trichostomatida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 3: Chonotrichida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 4: Suctorida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 5: Apostomatida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 6: Astomatida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 7: Hymenostomatida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 8: Thigmotrichida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 9: Peritrichida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 2: Spirotricha[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 1: Heterotrichida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 2: Oligotrichida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 3: Tintinnida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 4: Entodinomorphida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 5: Odontosstomatida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem 6: Hypotrichida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Filo Chrysophyta[editar | editar código-fonte]

- No Filo Chrysophyta existem três classes: Heterokontae (Xantophyceae), Chrysophyceae e Bacillariophyceae (Diatomeae). No total são cerca de 300 gêneros com aproximadamente 10.000 espécies

Classe Heterokontae (Xanthophyceae)[editar | editar código-fonte]

Classe Chrysophyceae[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ordem Heterotrichales[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Família Tribonemataceae

Ordem Heterosiphonales[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Família Botrydiaceae

- Família Vaucheriaceae

Ordem Chrysomonadales[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Família Coccolithophoridaceae

Classe Bacillariophyceae[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 1. Centricae[editar | editar código-fonte]

Subclasse 2. Pennatae[editar | editar código-fonte]

Filo Euglenophyta[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Compreende a este filo uma única classe com uma só ordem Euglenades.

Ordem 1: Euglenades[editar | editar código-fonte]

Filo Pyrrophyta[editar | editar código-fonte]

- O Filo Pyrrophyta possui 4 classes: Cryptophyceae, Chloromonadophyceae, Desmokontae e Dinophyceae.

Classe 1. Cryptophyceae[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Compreende a esta classe 4 ordens com 9 pequenas famílias.

Classe 2. Chloromonadophyceae[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Compreende a uma só ordem com uma só família.

Classe 3. Desmokontae[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Compreende a esta classe 4 ordens com 8 famílias.

Classe 4. Dinophyceae (Peridineae)[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Compreende a esta classe 7 ordens com 30 famílias.

- Principais gêneros: Dinophysis', Amphisolenia e o Ornithocercus, Dinophycea.