Usuário(a):JohnGotten/Testes

O Genocídio dos Sérvios (em servo-croata: Genocid nad Srbima, Геноцид над Србима) foi a perseguição sistemática aos sérvios que foi cometida durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial pelo regime fascista Ustaše no estado fantoche alemão nazista conhecido como o Estado Independente da Croácia (em servo-croata: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH) entre 1941 e 1945. Foi realizado por meio de execuções em campos de extermínio, bem como por meio de assassinatos em massa, limpeza étnica, deportações, conversões forçadas e estupro de guerra. Este genocídio foi realizado simultaneamente com o Holocausto no NDH, bem como o genocídio de Roma, combinando as políticas raciais nazistas com o objetivo final de criar uma Grande Croácia etnicamente pura.

A base ideológica do movimento Ustaše remonta ao século XIX. Vários nacionalistas e intelectuais croatas estabeleceram teorias sobre os sérvios como uma raça inferior. O legado da Primeira Guerra Mundial, bem como a oposição de um grupo de nacionalistas à unificação em um estado comum dos eslavos do sul, influenciou as tensões étnicas no recém-formado Reino dos Sérvios, Croatas e Eslovenos (desde 1929 Reino da Iugoslávia). A Ditadura real de 6 de janeiro e as posteriores políticas nas décadas de 1920 e 1930 alimentaram o surgimento de movimentos externos nazistas. Isso culminou com a ascensão da Ustaše, uma organização nazista e terrorista, fundada por Pavelić. O movimento foi apoiado financeira e ideologicamente por Benito Mussolini e Adolf Hitler, e também esteve envolvido no assassinato do rei Alexandre I.

Após a invasão do Eixo da Iugoslávia em abril de 1941, um estado fantoche alemão conhecido como o Estado Independente da Croácia (NDH) foi estabelecido, compreendendo a maior parte da atual Croácia e Bósnia e Herzegovina, bem como partes da atual Sérvia e Eslovênia. governado pelo Ustaše. O objetivo do Ustaše era criar uma Grande Croácia etnicamente pura, eliminando todos os não-croatas, com os sérvios sendo o alvo principal, judeus, ciganos e dissidentes políticos também foram alvos de eliminação. Massacres em grande escala foram cometidos e campos de concentração foram construídos, o maior deles foi em Jasenovac, que era conhecido por sua alta taxa de mortalidade e as práticas bárbaras que ocorriam nele. Além disso, o NDH foi o único estado fantoche do Eixo a estabelecer campos de concentração especificamente para crianças. O regime assassinou sistematicamente cerca de 200.000 a 500.000 sérvios. 300.000 sérvios foram expulsos e pelo menos 200.000 mais sérvios foram convertidos à força, a maioria dos quais se converteu após a guerra. Proporcional à população, o NDH foi um dos regimes mais letais do Europa.

Mile Budak e outros altos funcionários do NDH foram julgados e condenados por crimes de guerra pelas autoridades comunistas. Comandantes de campos de concentração como Ljubo Miloš e Miroslav Filipović foram capturados e executados, enquanto Aloisio Stepinac foi considerado culpado por conversão forçada. Muitos outros escaparam, incluindo o líder supremo nazista Ante Pavelić, a maioria para a América Latina, atraves do caminho dos ratos.

O genocídio não foi devidamente examinado no rescaldo da guerra, porque o governo comunista não encorajou acadêmicos independentes por temer que as tensões étnicas pudessem desestabilizar o novo regime com o dilema "Fraternidade e Irmandade. Hoje em dia, em 22 de abril, a Sérvia marca o feriado dedicado às vítimas de genocídio e do nazismo, enquanto a Croácia realiza uma comemoração oficial no Memorial Jasenovac.

Antecedentes[editar | editar código-fonte]

Muitos autores afirmam que o movimento Ustaše remonta ao século 19, quando Ante Starčević estabeleceu o Partido dos Direitos,[1] bem como quando Josip Frank separou sua fração extremista dele e formou seu próprio Puro Partido dos Direitos.[2] Starčević foi uma grande influência ideológica no nazismo croata da Ustaše.[3][4] Ele era um defensor da unidade e independência croata e era anti-Habsburgo,como Starčević viu o principal inimigo croata na Monarquia dos Habsburgos, e anti-sérvio.[3] Ele imaginou a criação de uma Grande Croácia Pura que incluiria territórios habitados por bósnios, sérvios e eslovenos, considerando os bósnios e sérvios como croatas convertidos ao islamismo e ao cristianismo ortodoxo oriental.[3]Em sua demonização doentia dos sérvios, ele afirmou "como os sérvios hoje são perigosos por suas idéias e composição racial, como há no sangue uma tendência para conspirações, revoluções e golpes".[5] Starčević chamou os sérvios de "raça impura", um "povo nômade" e "uma raça de escravos, as bestas mais repugnantes", enquanto o cofundador de seu partido, Eugen Kvaternik, negava a existência de sérvios na Croácia, vendo sua consciência política como uma ameaça.[6][7][8][9] O escritor Milovan Đilas cita Starčević como o "pai do racismo" e "pai ideológico" da Ustaše, enquanto mutios ideólogos Ustaše ligaram e apoiavam as idéias raciais de Starčević à ideologia racial de Adolf Hitler.[10][11] Predefinição:Genocide

O partido de Frank abraçou a posição de Starčević de que os sérvios são um obstáculo para as ambições políticas e territorialistas croatas, e as atitudes agressivas anti-sérvias se tornaram uma das principais características do partido[12][13][9][14] Os seguidores do ultranacionalista Partido de Direita Puro eram conhecidos como Frankista e se tornariam o principal grupo de membros do movimento Ustaše subsequente.[15][7][9][14] Após a derrota das Potências Centrais na Primeira Guerra Mundial e o colapso do Império Austro-Húngaro, o estado provisório foi formado nos territórios do sul do Império, que se juntou ao Reino da Sérvia, a do Aliados, para formar o Reino dos Sérvios, Croatas e Eslovenos (mais tarde conhecido como Iugoslávia), governados pela dinastia sérvia Karađorđević.O historiador John Paul Newman explicou que a influência dos frankistas, bem como o legado da Primeira Guerra Mundial, teve um impacto sobre a ideologia ustaše e seus futuros meios genocidas.[14][16]Muitos veteranos de guerra lutaram em várias fileiras e em várias frentes, tanto no lado "vitorioso" quanto no lado "derrotado" da guerra.[14] A Sérvia sofreu a maior taxa de baixas do mundo, enquanto os croatas lutaram no exército austro-húngaro e dois deles serviram como governadores militares da Bósnia e Sérvia ocupada.[17][16]Ambos endossaram os planos de desnacionalização da Áustria-Hungria em terras povoadas por sérvios e apoiaram a ideia de incorporar uma Sérvia escrava ao Império. Newman afirmou que a “oposição inabalável dos oficiais austro-húngaros à Iugoslávia forneceu um projeto para a direita radical croata, a Ustaše”.[16] Os frankistas culparam os sérvios pela derrota da Áustria-Hungria e se opuseram à criação da Iugoslávia.[14]

Os pseudo-intelectuais croatas do início do século 20 Ivo Pilar, Ćiro Truhelka e Milan Šufflay influenciaram o conceito da ustaše de nação e identidade racial, bem como a teoria racista dos sérvios.[18][19][20] Pilar, deu grande ênfase ao determinismo racista, argumentando que os croatas foram definidos pela herança racial e cultural “Nórdico-Ariana” (negando o fato inegavel de serem racialmente eslavos), enquanto os sérvios de com os Eslavônica Românica”.[21] Truhelka, afirmou que os "muçulmanos bósnios eram croatas étnicos" (negando o fato da bósnia ser historicamente dentro do estado sérvio), que, segundo ele, pertenciam à "raça nórdica racialmente superior". Por outro lado, os sérvios pertenciam à “raça corrompida”.[22][19] Os Ustaše promoveram as pseudos-teorias do político Šufflay, que se acredita ter afirmado que a Croácia foi "uma das mais fortes muralhas da civilização ocidental por muitos séculos"(da qual não é verdade, pois perdeu mais de 50% do territorio para o Imperio otomano, e que sem a vassalagem do Império Hungaro, a croacia seria anexada), que ele "afirmou ter sido perdida por meio de sua união com a Sérvia, quando a nação de Iugoslávia foi formada em 1918.[23]

A explosão do nazismo croata após 1918 foi uma das principais ameaças à estabilidade da Iugoslávia.[24] Durante a década de 1920, Ante Pavelić, político e um dos frankistas, emergiu como o principal porta-voz da independência croata.[9] Em 1927, ele secretamente contatou Benito Mussolini, ditador da Itália e fundador do fascismo, e apresentou suas idéias separatistas a ele.[25] Pavelić propôs uma Grande Croácia independente que deveria cobrir toda a área supostamente "histórica e étnica croata".[25] Nesse período, Mussolini se interessou pelos Bálcãs com o objetivo de expurgar a Iugoslávia, fortalecendo a influência fascista na costa leste do mar Adriático.[26] O historiador britânico Rory Yeomans afirma que há indícios de que Pavelić estava considerando a formação de algum tipo de grupo de insurgência nazista já em 1928.[27]

Em junho de 1928, Stjepan Radić, líder do maior e mais popular partido croata Partido Camponês Croata foi mortalmente ferido na câmara parlamentar por Puniša Račić, um líder montenegrino, ex-membro do Chetnik e deputado do governante do Partido Radical do Povo Sérvio. Račić também matou dois outros deputados do HSS e feriu mais dois.[28][14][29][30] As mortes provocaram violentos protestos em Zagreb.[28] Tentando suprimir o conflito entre os partidos políticos croatas e sérvios, o rei Alexandre I proclamou uma ditadura com o objetivo de estabelecer o “iugoslavismo integral” e uma única nação iugoslava.[31][15][32][33] A introdução da ditadura real colocou as forças separatistas em primeiro plano, especialmente entre croatas e macedônios.[34][24] A Ustaše emergiu como o movimento mais extremo deles.[35] O Ustaše foi criado no final de 1929 ou início de 1930 entre grupos radicais e militantes de estudantes e jovens, que existiam desde o final dos anos 1920.[28] Precisamente, o movimento foi fundado pelo jornalista Gustav Perčec e Ante Pavelić.[28] Eles foram movidos por um ódio doentio profundo e infundado contra sérvios e alegaram que, "croatas e sérvios estavam separados por um abismo cultural intransponível" que os impedia de viverem lado a lado.[23] Pavelić acusou o governo de Belgrado de propagar “uma "cultura bárbara" e "civilização cigana”, alegando que eles estavam propagando “ "a ortodoxia" na divina Croácia”.[36] Apoiadores do genocídio planejado de Ustaše anos antes da Segunda Guerra Mundial, por exemplo, um dos principais ideólogos de Pavelić, Mijo Babić, escreveu em 1932 que os Ustaše "limparão e cortarão tudo que difere do povo croata".[37] Em 1933, o Ustaše apresentou "Os Dezessete Princípios" que formaram a ideologia oficial do movimento. Os Princípios afirmavam a singularidade da nação croata, promoviam direitos coletivos sobre os direitos individuais e declaravam que as pessoas que não fossem croatas de "sangue" seriam expurgados.[38][39]

Para explicar o que viam como uma "máquina de terror", e regularmente referido como "alguns excessos" por indivíduos, os Ustaše citaram, entre outras coisas, as políticas do governo iugoslavo do entreguerras que descreveram como hegemonia sérvia "que custou a vida de mil croatas ”.[40] O historiador Jozo Tomasevich explica que esse argumento não é verdadeiro, alegando que entre dezembro de 1918 e abril de 1941 cerca de 280 croatas foram mortos por motivos políticos, e que nenhum motivo específico para os assassinatos pôde ser identificado, pois eles também podem estar ligados a confrontos durante o reforma agrária.[41] Além disso, afirmou que também os sérvios tiveram seus direitos civis e políticos negados durante a ditadura real. Isso culminou no movimento Ustaše e, em última análise, em suas políticas anti-sérvias na Segunda Guerra Mundial, que foram absurdamente desproporcionais às "medidas anti-croatas" anteriores, em natureza e extensão.[30] Yeomans explica que os oficiais de Ustaše enfatizaram balburdiavam os crimes contra os croatas cometidos pelo governo iugoslavo e pelas forças de segurança, embora muitos deles fossem imaginados, embora alguns deles reais, como justificativa para a ataque contra os sérvios.[42] A cientista política Tamara Pavasović Trošt, comentando a historiografia e os livros didáticos infantis da croacia, listou as alegações de que o terror contra os sérvios surgiu como resultado de "sua hegemonia anterior" (da qual nunca existiu), sendo isso um exemplo da relativização dos crimes de Ustaše.[43]O historiador Aristóteles Kallis explicou que as mentiras anti-sérvias eram uma "quimera" que emergiu da convivência na Iugoslávia com continuidade de estereótipos anteriores..[15]

Os Ustaše também funcionavam como uma organização terrorista.[44] O primeiro centro de Ustaše foi estabelecido em Viena, onde uma rápida propaganda anti-iugoslava logo se desenvolveu e agentes foram preparados para ações terroristas.[45] Eles organizaram o chamado levante Velebit em 1932, atacando uma delegacia de polícia na vila de Brušani em Lika.[46] Em 1934, os Ustaše cooperaram com nazistas búlgaros, húngaros e italianos para assassinar o rei Alexandre enquanto ele visitava a cidade francesa de Marselha.[35] As tendências nazistas de Pavelić ficaram mais aparentes.[9] O movimento Ustaše foi apoiado financeira e ideologicamente por Benito Mussolini.[47] Durante a intensificação dos laços com a Alemanha nazista na década de 1930, o conceito de nação croata de Pavelić tornou-se cada vez mais voltado para a raça.[36][48][49]

Estado Independente da Croácia[editar | editar código-fonte]

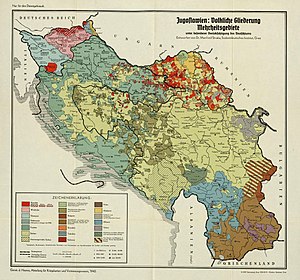

Serbs (incdluding Montenegrin Serbs)

Croats

Bosnian Muslims

Germans (Danube Swabians)

Em abril de 1941, o Reino da Iugoslávia foi invadido pelas potências do Eixo. Depois que as forças nazistas entraram em Zagreb em 10 de abril de 1941, o associado mais próximo de Pavelić, Slavko Kvaternik, proclamou a formação do Estado Independente da Croácia (NDH) em uma transmissão da Rádio Zagreb. Enquanto isso, Pavelić e várias centenas de voluntários Ustaše deixaram seus acampamentos na Itália e viajaram para Zagreb, onde Pavelić declarou um novo governo em 16 de abril de 1941.[50] Ele se atribuiu o título de "Poglavnik" (em alemão: Führer). The NDH combined most of modern Croatia, all of modern Bosnia and Herzegovina and parts of modern Serbia into an "Italian-German quasi-protectorate".[51] Serbs made up about 30% of the NDH population.[52] The NDH was never fully sovereign, but it was a puppet state that enjoyed the greatest autonomy than any other regime in German-occupied Europe.[49] The Independent State of Croatia was declared to be on Croatian "ethnic and historical territory".[53]

This country can only be a Croatian country, and there is no method we would hesitate to use in order to make it truly Croatian and cleanse it of Serbs, who have for centuries endangered us and who will endanger us again if they are given the opportunity.— Milovan Žanić, the minister of the NDH government, on 2 May 1941.[54]

The Ustaše became obsessed with creating an ethnically pure state.[55] As outlined by Ustaše ministers Mile Budak, Mirko Puk and Milovan Žanić, the strategy to achieve an ethnically pure Croatia was that:[56][57]

- One-third of the Serbs were to be killed

- One-third of the Serbs were to be expelled

- One-third of the Serbs were to be forcibly converted to Catholicism

According to historian Ivo Goldstein, this formula was never published but it is undeniable that the Ustaše applied it towards Serbs.[58]

The Ustaše movement received limited support from ordinary Croats.[59][60] In May 1941, the Ustaše had about 100,000 members who took the oath.[61][62][63] Since Vladko Maček reluctantly called on the supporters of the Croatian Peasant Party to respect and co-operate with the new regime of Ante Pavelić, he was able to use the apparatus of the party and most of the officials from the former Croatian Banovina.[64][65] Initially, Croatian soldiers who had previously served in the Austro-Hungarian army held the highest positions in the NDH armed forces.[66]

Historian Irina Ognyanova stated that the similarities between the NDH and the Third Reich included the assumption that terror and genocide were necessary for the preservation of the state.[67] Viktor Gutić made several speeches in early summer 1941, calling Serbs "former enemies" and "unwanted elements" to be cleansed and destroyed, and also threatened Croats who did not support their cause.[68] Much of the ideology of the Ustaše was based on Nazi racial theory. Like the Nazis, the Ustaše deemed Jews, Romani, and Slavs to be sub-humans (Untermensch). They endorsed the claims from German racial theorists that Croats were not Slavs but a Germanic race. Their genocides against Serbs, Jews, and Romani were thus expressions of Nazi racial ideology.[69] Adolf Hitler supported Pavelić in order to punish the Serbs.[70] Historian Michael Phayer explained that the Nazis’ decision to kill all of Europe's Jews is estimated by some to have begun in the latter half of 1941 in late June which, if correct, would mean that the genocide in Croatia began before the Nazi killing of Jews.[71] Jonathan Steinberg stated that the crimes against Serbs in the NDH were the “earliest total genocide to be attempted during the World War II”.[71]

Andrija Artuković, the Minister of Interior of the Independent State of Croatia, signed into law a number of racial laws.[72] On 30 April 1941, the government adopted “the legal order of races” and “the legal order of the protection of Atyan blood and the honor of Croatian people”.[72] Croats and about 750,000 Bosnian Muslims, whose support was needed against the Serbs, were proclaimed Aryans.[10] Donald Bloxham and Robert Gerwarth concluded that Serbs were primary target of racial laws and murders.[73] The Ustaše introduced the laws to strip Serbs of their citizenship, livelihoods, and possessions.[38] Similar to Jews in the Third Reich, Serbs were forced to wear armbands bearing the letter “P”, for Pravoslavac (Orthodox).[38][9] Ustaše writers adopted dehumanizing rhetoric. [74][75] In 1941, the usage of the Cyrillic script was banned,[76] and in June 1941 began the elimination of "Eastern" (Serbian) words from the Croatian language, as well as the shutting down of Serbian schools.[77] Ante Pavelić ordered, through the "Croatian state office for language", the creation of new words from old roots (some which are used today), and purged many Serbian words.[78]

Concentration and extermination camps[editar | editar código-fonte]

The Ustaše set up temporary concentration camps in the spring of 1941 and laid the groundwork for a network of permanent camps in autumn.[79] The creation of concentration camps and extermination campaign of Serbs had been planned by the Ustaše leadership long before 1941.[42] In Ustaše state exhibits in Zagreb, the camps were portrayed as productive and "peaceful work camps", with photographs of smiling inmates.[80]

Serbs, Jews and Romani were arrested and sent to concentration camps such as Jasenovac, Stara Gradiška, Gospić and Jadovno. There were 22–26 camps in NDH in total.[81] Historian Jozo Tomasevich described that the Jadovno concentration camp itself acted as a "way station" en route to pits located on Mount Velebit, where inmates were executed and dumped.[82]

The largest and most notorious camp was the Jasenovac-Stara Gradiška complex,[79] the largest extermination camp in the Balkans.[83] An estimated 100,000 inmates perished there, most Serbs.[84] Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić, the commander-in-chief of all the Croatian camps, announced the great "efficiency" of the Jasenovac camp at a ceremony on 9 October 1942, and also boasted: "We have slaughtered here at Jasenovac more people than the Ottoman Empire was able to do during its occupation of Europe."[85]

Bounded by rivers and two barbed-wire fences making escape unlikely, the Jasenovac camp was divided into five camps, the first two closed in December 1941, while the rest were active until the end of the war. Stara Gradiška (Jasenovac V) held women and children. The Ciglana (brickyards, Jasenovac III) camp, the main killing ground and essentially a death camp, had 88% mortality rate, higher than Auschwitz's 84.6%.[86] A former brickyard, a furnace was engineered into a crematorium, with witness testimony of some, including children, being burnt alive and stench of human flesh spreading in the camp.[87] Luburić had a gas chamber built at Jasenovac V, where a considerable number of inmates were killed during a three-month experiment with sulfur dioxide and Zyklon B, but this method was abandoned due to poor construction.[88] Still, that method was unnecessary, as most inmates perished from starvation, disease (especially typhus), assaults with mallets, maces, axes, poison and knives.[88] The srbosjek ("Serb-cutter") was a glove with an attached curved blade designed to cut throats.[88] Large groups of people were regularly executed upon arrival outside camps and thrown into the river.[88] Unlike German-run camps, Jasenovac specialized in brutal one-on-one violence, such as guards attacking barracks with weapons and throwing the bodies in the trenches.[88] Some historians use a sentence from German sources: “Even German officers and SS men lost their cool when they saw (Ustaše) ways and methods.”[89]

The infamous camp commander Filipović, dubbed fra Sotona ("brother Satan") and the "personification of evil", on one occasion drowned Serb women and children by flooding a cellar.[88] Filipović and other camp commanders (such as Dinko Šakić and his wife Nada Šakić, the sister of Maks Luburić), used ingenious torture.[88] There were throat-cutting contests of Serbs, in which prison guards made bets among themselves as to who could slaughter the most inmates. It was reported that guard and former Franciscan priest Petar Brzica won a contest on 29 August 1942 after cutting the throats of 1,360 inmates.[90] Inmates were tied and hit over the head with mallets and half-alive hung in groups by the Granik ramp crane, their intestines and necks slashed, then dropped into the river.[91] When the Partisans and Allies closed in at the end of the war, the Ustaše began mass liquidations at Jasenovac, marching women and children to death, and shooting most of the remaining male inmates, then torched buildings and documents before fleeing.[92] Many prisoners were victims of rape, sexual mutilation and disembowelment, while induced cannibalism amongst the inmates also took place.[93][94][95][96][97] Some survivors testified about drinking blood from the slashed throats of the victims and soap making from human corpses.[98][95][97][99]

Children's concentration camps[editar | editar código-fonte]

The Independent State of Croatia was the only Axis satellite to have erected camps specifically for children.[79] Special camps for children were those at Sisak, Đakovo and Jastrebarsko,[100] while Stara Gradiška held thousands of children and women.[86] Historian Tomislav Dulić explained that the systematic murder of infants and children, who could not pose a threat to the state, serves as one of the important illustration of the genocidal character of Ustaša mass killing.[101]

The Holocaust and genocide survivors, including Božo Švarc, testified that Ustaše tore off the children's hands, as well as, “apply a liquid to children’s mouths with brushes”, which caused the children to scream and later die.[38] The Sisak camp commander, aphysician Antun Najžer, was dubbed the "Croatian Mengele" by survivors.[102]

Diana Budisavljević, a humanitarian of Austrian descent, carried out rescue operations and saved more than 15,000 children from Ustaše camps.[103][104]

List of concentration and death camps[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Jasenovac (I–IV) — around 100,000 inmates perished there, at least 52,000 Serbs

- Stara Gradiška (Jasenovac V) — more than 12,000 inmates lost their lives, mostly Serbs

- Gospić — between 24,000 and 42,000 inmates died, predominantly Serbs

- Jadovno — between 15,000 and 48,000 Serbs and Jews perished there

- Slana and Metajna — between 4,000 and 12,000 Serbs, Jews and communists died

- Sisak — 6,693 children passed through the camp, mostly Serbs, between 1,152 and 1,630 died

- Danica — around 5,000, mostly Serbs, were transported to the camp, some of them were executed

- Jastrebarsko — 3,336 Serb children passing through the camp, between 449 and 1,500 died

- Kruščica — around 5,000 Jews and Serbs were interred at the camp, while 3,000 lost their lives

- Đakovo — 3,800 Jewish and Serb women and children were interred at the camp, at least 569 died

- Lobor — more than 2,000 Jewish and Serb women and children were interred, at least 200 died

- Kerestinec — 111 Serbs, Jews and communists were captured, 85 were killed

- Sajmište — the camp at the NDH territory operated by the Einsatzgruppen and since May 1944 by Ustaše; between 20,000 and 23,000 Serbs, Jews, Roma and anti-fascists died here

- Hrvatska Mitrovica — the concetration camp in Sremska Mitrovica

Massacres[editar | editar código-fonte]

A large number of massacres were committed by the NDH armed forces, Croatian Home Guard (Domobrani) and Ustaše Militia.

The Ustaše Militia was organised in 1941 into five (later 15) 700-man battalions, two railway security battalions and the elite Black Legion and Poglavnik Bodyguard Battalion (later Brigade). They were predominantly recruited among the uneducated population and working class.

Violence against Serbs began in April 1941 and was initially limited in scope, primarily targeting Serb intelligentsia. By July however, the violence became "indiscriminate, widespread and systematic". Massacres of Serbs were focused in mixed areas with large Serb populations for necessity and efficiency.[105]

In the summer of 1941, Ustaše militias and death squads burnt villages and killed thousands of civilian Serbs in the country-side in sadistic ways with various weapons and tools. Men, women, children were hacked to death, thrown alive into pits and down ravines, or set on fire in churches.[68] Some Serb villages near Srebrenica and Ozren were wholly massacred while children were found impaled by stakes in villages between Vlasenica and Kladanj.[106] The Ustaše cruelty and sadism shocked even Nazi commanders.[107] A Gestapo report to Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, dated 17 February 1942, stated:

Increased activity of the bands [of rebels] is chiefly due to atrocities carried out by Ustaše units in Croatia against the Orthodox population. The Ustaše committed their deeds in a bestial manner not only against males of conscript age, but especially against helpless old people, women and children. The number of the Orthodox that the Croats have massacred and sadistically tortured to death is about three hundred thousand.[108]

Charles King emphasized that concentration camps are losing their central place in Holocaust and genocide research because a large proportion of victims perished in mass executions, ravines and pits.[109] He explained that the actions of the German allies, including the Croatian one, and the town- and village-level elimination of minorities also played a significant role.[109]

Central Croatia[editar | editar código-fonte]

On 28 April 1941, approximately 184–196 Serbs from Bjelovar were summarily executed, after arrest orders by Kvaternik. It was the first act of mass murder committed by the Ustaše upon coming to power, and presaged the wider campaign of genocide against Serbs in the NDH that lasted until the end of the war. A few days following the massacre of Bjelovar Serbs, the Ustaše rounded up 331 Serbs in the village of Otočac. The victims were forced to dig their own graves before being hacked to death with axes. Among the victims was the local Orthodox priest and his son. The former was made to recite prayers for the dying as his son was killed. The priest was then tortured, his hair and beard was pulled out, eyes gouged out before he was skinned alive.[110]

On 24–25 July 1941, the Ustaše militia captured the village of Banski Grabovac in the Banija region and murdered the entire Serb population of 1,100 peasants. On 24 July, over 800 Serb civilians were killed in the village of Vlahović.[105]

Between 29 and 37 July 1941, 280 Serbs were killed and thrown into pits near Kostajnica.[111] Large scale massacres took place in Staro Selo Topusko,[112] Vojišnica[113] and Vrginmost[114] About 60% of Sadilovac residents lost their lives during the war.[115] More than 400 Serbs were killed in their homes, including 185 children.[115] On 31 July 1942, in the Sadilovac church the Ustaše under Milan Mesić's command massacred more than 580 inhabitants of the surrounding villages, including about 270 children.[116]

Glina[editar | editar código-fonte]

On 11 or 12 May 1941, 260–300 Serbs were herded into an Orthodox church and shot, after which it was set on fire. The idea for this massacre reportedly came from Mirko Puk, who was the Minister of Justice for the NDH.[117] On 10 May, Ivica Šarić, a specialist for such operations traveled to the town of Glina to meet with local Ustaše leadership where they drew up a list of names of all the Serbs between sixteen and sixty years of age to be arrested.[118] After much discussion, they decided that all of the arrested should be killed.[119] Many of the town's Serbs heard rumors that something bad was in store for them but the vast majority did not flee. On the night of 11 May, mass arrests of male Serbs over the age of sixteen began.[119] The Ustaše then herded the group into an Orthodox Church and demanded that they be given documents proving the Serbs had all converted to Catholicism. Serbs who did not possess conversion certificates were locked inside and massacred.[110] The church was then set on fire, leaving the bodies to burn as Ustaše stood outside to shoot any survivors attempting to escape the flames.[120]

A similar massacre of Serbs occurred on 30 July 1941. 700 Serbs were gathered into a church under the premise that they would be converted. Victims were killed by having their throats cut or by having their heads smashed in with rifle butts. Between 500 and 2000 other Serbs were later massacred in neighbouring villages by Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić's forces, continuing until 3 August. In these massacres specifically males 16 years and older were killed.[121] Only one of the victims, Ljubo Jednak, survived by playing dead.

Lika[editar | editar código-fonte]

The district of Gospić experienced the first large-scale massacres which occurred in the Lika region, as some 3,000 Serb civilians were killed between late July and early August 1941.[105] Ustaše officials reported an emerging Serb rebellion due to massacres. In late July 1941, a detachment of the Croatian military in Gospić noted that the local insurgents were Serb peasants who had fled to the woods "purely as a reaction to the cleansing [operations] against them by our Ustaša formations". Following a sabotage of railway tracks in the district of Vojnić that was attributed to local communists on 27 July 1941, the Ustaše began a "cleansing" operation of indiscriminate pillage and killing of civilians, including the elderly and children.[105]

On 6 August 1941, the Ustaše killed and burned more than 280 villagers in Mlakva, including 191 children.[122] Between June and August 1941, about 890 Serbs from Ličko Petrovo Selo and Melinovac were killed and thrown in the so-called Delić pit.[123]

During the war, the Ustaše massacred more than 900 Serbs in Divoselo, more than 500 in Smiljan, as well as more than 400 in Široka Kula near Gospić.[124] On 2 August 1941, the Ustaše trapped about 120 children and women and 50 men who tried to escape from Divoselo. After a few days of imprisonment, where women were raped, they were stabbed in groups and thrown into the pits.[125]

Slavonia[editar | editar código-fonte]

On 21 December 1941, approximately 880 Serbs from Dugo Selo Lasinjsko and Prkos Lasinjski were killed in the Brezje forest.[126] On the Serbian New Year, 14 January 1942, the biggest slaughter of the civilians from Slavonia started. Villages were burned, and about 350 people were deported to Voćin and executed.[127]

Syrmia[editar | editar código-fonte]

In August 1942, following the joint military anti-partisan operation in the Syrmia by the Ustaše and German Wehrmacht, it turned into a massacre by the Ustaše militia that left up to 7,000 Serbs dead.[128] Among those killed was the prominent painter Sava Šumanović, who was arrested along with 150 residents of Šid, and then tortured by having his arms cut off.[129]

Bosnian Krajina[editar | editar código-fonte]

In August 1941 on the Eastern Orthodox Elijah's holy day, who is the patron saint of Bosnia and Herzegovina, between 2,800 and 5,500 Serbs from Sanski Most and the surrounding area were killed and thrown into pits which have been dug by victims themselves.[130]

During the war, the NDH armed forces killed over 7,000 Serbs in the municipality of Kozarska Dubica, while the municipality lost more than half of its pre-war population.[131] The biggest massacre was committed by the Croatian Home Guard in January 1942, when the village Draksenić was burned and more than 200 were people killed.[132]

In February 1942, the Ustaše under Miroslav Filipović's command massacred 2,300 adults and 550 children in Serb-populated villages Drakulić, Motike and Šargovac.[133] The children were chosen as the first victims and their body parts were cut off.[133]

Garavice[editar | editar código-fonte]

From July to September 1941, thousands of Serbs were massacred along with some Jews and Roma victims at Garavice, an extermination location near Bihać. On the night of 17 June 1941, Ustaše began the mass killing of previously captured Serbs, who were brought by trucks from the surrounding towns to Garavice.[134] The bodies of the victims were thrown into mass graves. A large amount of blood contaminated the local water supply.[135]

Herzegovina[editar | editar código-fonte]

On 9 May 1941, approximately 400 Serbs were rounded up from several villages and executed in a pit behind a school in the village of Blagaj.[136] From 4–6 August 1941, 650 women and children killed by being thrown into the Golubinka pit near Šurmanci.[38][137] Also, hand grenades were thrown at dead bodies.[137] Some 4000 Serbs later massacred in neighbouring places during that summer.[38]

On 2 June 1941, Ustaše authorities in the municipality of Gacko issued an order to the Serb inhabitants of the villages of Korita and Zagradci demanding that all males above the age of fifteen report to a building in the village of Stepen. Once there, they were imprisoned for two days and on 4 June, the prisoners who numbered about 170 were tied together in groups of two or three, loaded onto a lorry and driven to the Golubnjača limestone pit near Kobilja Glava where they were shot, beaten with poles, cudgels, axes and picks and thrown into the pit.[138] On June 23, another 80 people from three villages near Gacko were killed.[139]

On 2 June 1941, the Ustaše killed 140 peasants near the town of Ljubinje and on 23 June killed an additional 160. In the municipality of Stolac, nearly 260 were killed during the course of two days.[139]

In the Livno Field area, the Ustaše killed over 1,200 Serbs includiing 370 children.[140] In the Koprivnica Forest near Livno, around 300 citizen were tortured and killed.[140] About 300 children, women and the elderly were killed and thrown into the Ravni Dolac pit in Donji Rujani.[141]

Drina Valley[editar | editar código-fonte]

Some 70-200 Serbs massacred by Muslim Ustaše forces in Rašića Gaj, Vlasenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina between 22 June and 20 July 1941, after raping women and girls.[142] Many Serbs were executed by Ustaše along the Drina Valley for a months, especially near Višegrad.[38] Jure Francetić's Black Legion killed thousands of defenceless Bosnian Serb civilians and threw their bodies into the Drina river.[143] In 1942, about 6,000 Serbs were killed in Stari Brod near Rogatica and Miloševići.[144][145]

Sarajevo[editar | editar código-fonte]

During the summer of 1941, Ustaše militia periodically interned and executed groups of Sarajevo Serbs.[146] In August 1941, they arrested about one hundred Serbs suspected of ties to the resistance armies, mostly church officials and members of the intelligentsia, and executed them or deported the to concentration camps.[146] The Ustaše killed at least 323 people in the Villa Luburić, a slaughter house and place for torturing and imprisoning Serbs, Jews and political dissidents.[147]

Expulsion and ethnic cleansing[editar | editar código-fonte]

Expulsions was one of the pillar of the Ustaše plan to create a pure Croat state.[38] The first to be forced to leave were war veterans from the World War I Macedonian front who lived in Slavonia and Syrmia.[38][148] By mid-1941, 5,000 Serbs had been expelled to German-occupied Serbia.[38] The general plan was to have prominent people deported first, so their property could be nationalized and the remaining Serbs could then be more easily manipulated. By the end of September 1941, about half of the Serbian Orthodox clergy, 335 priests, had been expelled.[149]

The Drina is the border between the East and West. God’s Providence placed us to defend our border, which our allies are well aware and value, because for centuries we have proven that we are good frontiersmen.[38]— Mile Budak, the minister of the NDH government, August 1941.

Advocates of expulsion presented it as a necessary measure for the creation of a socially functional nation state, and also rationalized these plans by comparing it with the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey.[150] The Ustaše set up holding camps, with the aim of gathering a large number of people and deporting them.[38] The NDH government also formed the Office of Colonization to resettle Croats on reclaimed land.[38] During the summer of 1941, the expulsions were carried out with the significant participation of the local population.[151] Many representatives of local elites, including Bosnian Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Germans in Slavonia and Syrmia, played an active role in the expulsion.[152]

An estimated 120,000 Serbs were deported from the NDH to German-occupied Serbia, and 300,000 fled by 1943.[153] By the end of July 1941 according to the German authorities in Serbia, 180,000 Serbs defected from the NDH to Serbia and by the end of September that number exceeded 200,000. In that same period 14,733 persons were legally relocated from the NDH to Serbia.[148]In October 1941, organized migration was stopped because the German authorities in Serbia forbid further immigration of Serbs. According to documentation of the Commissariat for Refugees and Immigrants in Belgrade, in 1942 and 1943 illegal departures of individuals from NDH to Serbia still existed, numbering an estimated 200,000 though these figures are incomplete.[148]

Religious persecution[editar | editar código-fonte]

The Ustaše viewed religion and nationality as being closely linked; while Roman Catholicism and Islam (Bosnian Muslims were viewed as Croats) were recognized as Croatian national religions, Eastern Orthodoxy was deemed inherently incompatible with the Croatian state project.[23] They saw Orthodoxy as hostile because it was identified as Serb.[154] On 3 May 1941 a law was passed on religious conversions, pressuring Serbs to convert to Catholicism and thereby adopt Croat identity.[23] This was made on the eve of Pavelić's meeting with Pope Pious XII in Rome.[155] The Catholic Church in Croatia, headed by archbishop Aloysius Stepinac, greeted it and adopted it into the Church's internal law.[155] The term "Serbian Orthodox" was banned in mid-May as being incompatible with state order, and the term "Greek-Eastern faith" was used in its place.[156] By the end of September 1941, about half of the Serbian Orthodox clergy, 335 priests, had been expelled.[149]

The Ustaša movement is based on religion. Therefore, our acts stem from our devotion to religion and the Roman Catholic church.— the chief Ustaše ideologist Mile Budak, 13 July 1941.[157]

Ustaše propaganda legitimized the persecution as being partially based on the historic Catholic–Orthodox struggle for domination in Europe and Catholic intolerance towards the "schismatics".[154] Following the Serb insurgency which was provoked by the Ustaše's reign of terror, killings and deportation campaign, the State Directorate for Regeneration launched a program in the autumn of 1941 which was aimed at the mass forced conversion of the Serbs.[154] Already in the summer, the Ustaše had closed or destroyed most of the Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries and deported, imprisoned or murdered Orthodox priests and bishops.[154] Over 150 Serbian Orthodox priests were also killed between May and December 1941.[158] The conversions were meant to Croatianize and permanently destroy the Serbian Orthodox Church.[154] Roman Catholic priest Krunoslav Draganović argued that many Catholics were converted to Orthodoxy during the 16th and 17th centuries, which was later used as the basis for the Ustaše conversion program.[159][160]

The Vatican was not opposed to the forced conversions. On 6 February 1942, Pope Pious XII privately received 206 Ustaše members in uniforms and blessed them, symbolically supporting their actions.[161] On 8 February 1942 envoy to the Holy See Rusinović said that 'the Holy See joyed' over forced conversions.[162] In a 21 February 1942 letter to Cardinal Luigi Maglione, the Holy See's secretary encouraged the Croatian bishops to speed up the conversions, and he also stated that the term "Orthodox" should be replaced with the terms "apostates or schismatics".[163] Many fanatical Catholic priests joined the Ustaše, blessed and supported their work, and participated in killings and conversions.[164]

In 1941–1942,[165] some 200,000[166] or 240,000[167]–250,000[168] Serbs were converted to Roman Catholicism, although most of them only practiced it temporarily.[166] Converts would sometimes be killed anyway, often in the same churches where they were re-baptized.[166] 85% of the Serbian Orthodox clergy was killed or expelled.[169] In Lika, Kordun and Banija alone, 172 Serbian Orthodox churches were closed, destroyed, or plundered.[156] On 2 July 1942, the Croatian Orthodox Church was founded in order to replace the institutions of the Serbian Orthodox Church,[170] after the matter of forced conversion had become extremely controversial.[23]

The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust described that the bishops' conference that met in Zagreb in November 1941 was not prepared to denounce the forced conversion of Serbs that had taken place in the summer of 1941, let alone condemn the persecution and murder of Serbs and Jews.[171] Many Catholic priests in Croatia approved of and supported the Ustaše's large scale attacks on the Serbian Orthodox Church,[172] and the Catholic hierarchy did not issue any condemnation of the crimes, either publicly or privately.[173] In fact, The Croatian Catholic Church and the Vatican viewed the Ustaše's policies against the Serbs as being advantageous to Roman Catholicism.[174]

Persecution of Serbian Orthodox clergy[editar | editar código-fonte]

Bishops and metropolitans of the Serbian Orthodox Church dioceses in the Independent State of Croatia were targeted during religious persecutions.[175] On 5 May 1941, the Ustaše tortured and killed Platon Jovanović of Banja Luka. On 12 May, Bishop Petar Zimonjić, Metropolitan of the Eparchy of Dabar-Bosna, was killed and in mid-August Bishop Sava Trlajić was killed.[158] Dositej Vasić, the Metropolitan of the Metropolitanate of Zagreb and Ljubljana died in 1945 as result of wounds from torture by Ustaše. Nikola Jovanović, the Bishop of the Eparchy of Zahumlje and Herzegovina died in 1944, after he was beaten by the Ustaše and expelled to Serbia. Irinej Đorđević, the Bishop of the Eparchy of Dalmatia was interned to Italian captivity.[175] There were 577 Serbian Orthodox priests, monks and other religious dignitaries in the NDH in April 1941. By December, there were none left. Between 214 and 217 were killed, 334 were exiled, eighteen fled and five died of natural causes.[175] In Bosnia and Herzegovina, 71 Orthodox priests were killed by the Ustaše during WWII, 10 by the Partisans, 5 by the Germans, and 45 died in the first decade after the end of WWII.[176]

The role of Aloysius Stepinac[editar | editar código-fonte]

A cardinal Aloysius Stepinac served as Archbishop of Zagreb during World War II and pledged his loyalty to the NDH. Scholars still debate the degree of Stepinac's contact with the Ustaše regime.[38] Mark Biondich stated that he was not an “ardent supporter” of the Ustahsa regime legitimising their every policy, nor an “avowed opponent” publicly denounced its crimes in a systematic manner.[177] While some clergy committed war crimes in the name of the Catholic Church, Stepinac practiced a wary ambivalence.[178][38] He was an early supporter of the goal of creating an Catholic Croatia, but soon began to question the regime's mandate of forced conversion.[38]

Historian Tomasevich praised his statements that were made against the Ustaše regime by Stepinac, as well as his actions against the regime. However, he also noted that these same statements and actions had shortcomings in respect to Ustaše's genocidal actions against the Serbs and the Serbian Orthodox Church. As Stepinac failed to publicly condemn the genocide waged against the Serbs by the Ustaše earlier during the war as he would later on. Tomasevich stated that Stepinac's courage against the Ustaše state earned him great admiration among anti-Ustaše Croats in his flock along with many others. However this came with the price of enmity of the Ustaše and Pavelić personally. In the early part of the war, he strongly supported a Yugoslavian state organized with federal lines. It was generally known that Stepinac and Pavlović thoroughly hated each other. [179] The Germans considered him Pro-Western and “friend of the Jews” leading to hostility from German and Italian forces. [180]

On 14 May 1941, Stepinac received word of an Ustaše massacre of Serb villagers at Glina. On the same day, he wrote to Pavelić saying:[181]

I consider it my bishop's responsibility to raise my voice and to say that this is not permitted according to Catholic teaching, which is why I ask that you undertake the most urgent measures on the entire territory of the Independent State of Croatia, so that not a single Serb is killed unless it is shown that he committed a crime warranting death. Otherwise, we will not be able to count on the blessing of heaven, without which we must perish.

These were still private protest letters. Later in 1942 and 1943, Stepinac started to speak out more openly against the Ustaše genocides, this was after most of the genocides were already committed, and it became increasingly clear the Nazis and Ustaše will be defeated.[182] In May 1942, Stepinac spoke out against genocide, mentioning Jews and Roma, but not Serbs.[38]

Tomasevich wrote that while Stepinac is to be commended for his actions against the regime, the failure of the Croatian Catholic hierarchy and Vatican to publicly condemn the genocide "cannot be defended from the standpoint of humanity, justice and common decency".[183] In his diary, Stepinac said that "Serbs and Croats are of two different worlds, north and south pole, which will never unite as long as one of them is alive", along with other similar views.[184] Historian Ivo Goldstein described that Stepinac was being sympathetic to the Ustaše authorities and ambivalent towards the new racial laws, as well as that he was “a man with many dilemmas in a disturbing time”.[185] Stepinac resented the interwar conversion of some 200,000 most Croatian Catholics to Orthodoxy, which he felt was forced on them by prevailing political conditions. [183] In 2016 Croatia's rehabilitation of Stepinac was negatively received in Serbia and Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[186]

Toll of victims and genocide classification[editar | editar código-fonte]

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website states that "Determining the number of victims for Yugoslavia, for Croatia, and for Jasenovac is highly problematic, due to the destruction of many relevant documents, the long-term inaccessibility to independent scholars of those documents that survived, and the ideological agendas of postwar partisan scholarship and journalism".[187]

In the 1980s, calculations of World War II victims in Yugoslavia were made by the Serb statistician Bogoljub Kočović and the Croat demographer Vladimir Žerjavić. Tomasevich described their studies as being objective and reliable.[188] Kočović estimated that 370,000 Serbs, both combatants and civilians, died in the NDH during the war. With a possible error of around 10%, he noted that Serb losses cannot be higher than 410,000.[189] He did not estimate the number of Serbs who were killed by the Ustaše, saying that in most cases, the task of categorizing the victims would be impossible.[190] Žerjavić estimated that the total number of Serb deaths in the NDH was 322,000, of which 125,000 died as combatants, while 197,000 were civilians. Žerjavić estimated that a total of 78,000 civilians were killed in Ustaše prisons, pits and camps, including Jasenovac, 45,000 civilians were killed by the Germans, 15,000 civilians were killed by the Italians, 34,000 civilians were killed in battles between the warring parties, and 25,000 civilians died of typhoid.[191] The number of victims who perished in the Jasenovac concentration camp remains a matter of debate, but current estimates put the total number at around 100,000, about half of whom were Serbs.[84]

During the war as well as during Tito's Yugoslavia, various numbers were given for Yugoslavia's overall war casualties.Predefinição:Cref2 Estimates by Holocaust memorial centers also vary.Predefinição:Cref2 The historian Jozo Tomasevich said that the exact number of victims in Yugoslavia is impossible to determine.[192] The academic Barbara Jelavich however cites Tomasevich's estimate in writing that as many as 350,000 Serbs were killed during the period of Ustaše rule.[193] The historian Rory Yeomans said that the most conservative estimates state that 200,000 Serbs were killed by Ustaše death squads but the actual number of Serbs who were executed by the Ustaše or perished in Ustaše concentration camps may be as high as 500,000.[79] In a 1992 work, Sabrina P. Ramet cites the figure of 350,000 Serbs who were "liquidated" by "Pavelić and his Ustaše henchmen".[194] In a 2006 work, Ramet estimated that at least 300,000 Serbs were "massacred by the Ustaše".[153] In her 2007 book "The Independent State of Croatia 1941-45", Ramet cites Žerjavić's overall figures for Serb losses in the NDH.[195] Marko Attila Hoare writes that "perhaps nearly 300,000 Serbs" died as a result of the Ustaše genocide and the Nazi policies.[196]

Tomislav Dulić stated that Serbs in NDH suffered among the highest casualty rates in Europe during the World War II.[101] The genocide scholar Israel Charny lists the Independent State of Croatia as the third most lethal regime in the twentieth century, killing an average of 2.51% of its citizens per year.[197] Charny's definition of domestic democide doesn't only include genocide, but also politicide and mass murder, as well as forced deportation causing deaths and famine or epidemic during which regime withhold aid or act in a way to make it more deadly.[198] American historian Stanley G. Payne stated that direct and indirect executions by NDH regime were an “extraordinary mass crime”, which in proportionate terms exceeded any other European regime beside Hitler's Third Reich.[199] He added the crimes in the NDH were proportionately surpassed only by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and several of the extremely genocidal African regimes.[199] Raphael Israeli wrote that “a large scale genocidal operations, in proportions to its small population, remain almost unique in the annals of wartime Europe.”[60]

In Serbia as well as in the eyes of Serbs, the Ustaše atrocities constituted a genocide.[200] Many historians and authors describe the Ustaše regime's mass killings of Serbs as meeting the definition of genocide, including Raphael Lemkin who is known for coining the word genocide and initiating the Genocide Convention.[201][202][203][204] Croatian historian Mirjana Kasapović explained that in the most important scientific works on genocide, crimes against Serbs, Jews and Roma in the NDH are unequivocally classified as genocide.[205]

Yad Vashem, Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, stated that “Ustasha carried out a Serb genocide, exterminating over 500,000, expelling 250,000, and forcing another 250,000 to convert to Catholicism”.[206][207] The Simon Wiesenthal Center, also, mentioned that leaders of the Independent State of Croatia committed genocide against Serbs, Jews, and Roma.[208] Presidents of Croatia, Stjepan Mesić and Ivo Josipović, as well as Bakir Izetbegović and Željko Komšić, Bosniak and Croat member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, also described the persecution of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia as a genocide.[209][210][211][212]

In the post-war era, the Serbian Orthodox Church considered the Serbian victims of this genocide to be martys. As a result, the Serbian Orthodox Church commemorates the Holy New Martys of Jasenovac Concentration Camp on 13 September.[213]

Aftermath[editar | editar código-fonte]

The Yugoslav communist authorities did not use the Jasenovac camp as was done with other European concentration camps, most likely due to Serb-Croat relations. They recognized that ethnic tensions stemming from the war could had the capacity to destabilize the new communist regime, tried to conceal wartime atrocities and to mask specific ethnic losses.[9] The Tito's government attempted to let the wounds heal and forge "brotherhood and unity" in the peoples.[214] Tito himself was invited to, and passed Jasenovac several times, but never visited the site.[215] The genocide was not properly examined in the aftermath of the war, because the Yugoslav communist government did not encourage independent scholars.[187][216][217][218] Historians Marko Attila Hoare and Mark Biondich stated that Western world historians don't pay enough attention to the genocide committed by Ustaše, while several scholars described it as lesser-known genocide.[38][219][205]

World War II and especially its ethnic conflicts have been deemed instrumental in the later Yugoslav Wars (1991–95).[220]

Trials[editar | editar código-fonte]

Mile Budak and a number of other members of the NDH government, such as Nikola Mandić and Julije Makanec, were tried and convicted of high treason and war crimes by the communist authorities of the SFR Yugoslavia. Many of them were executed.[221][222] Miroslav Filipović, the commandant of the Jasenovac and Stara Gradiška camps, was found guilty for war crimes, sentenced to death and hanged.[223]

Many others escaped, including the supreme leader Ante Pavelić, most to Latin America. Some emigrations were prevented by the Operation Gvardijan, in which Ljubo Miloš, the commandant of the Jasenovac camp was captured and executed.[224] Aloysius Stepinac, who served as Archbishop of Zagreb was found guilty of high treason and forced conversion of Orthodox Serbs to Catholicism.[225] However, some claim the trial was "carried out with proper legal procedure".[225]

In its judgment in the Hostages Trial, the Nuremberg Military Tribunal concluded that the Independent State of Croatia was not a sovereign entity capable of acting independently of the German military, despite recognition as an independent state by the Axis powers.[226] According to the Tribunal, "Croatia was at all times here involved an occupied country".[226] The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide were not in force at the time. It was unanimously adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948 and entered into force on 12 January 1951.[227][228]

Andrija Artuković, Minister of Internal Affairs and Minister of Justice of the NDH who signed a number of racial laws, escaped to the United States after the war and he was extradited to Yugoslavia in 1986, where he was tried in the Zagreb District Court and was found guilty of a number of mass killings in the NDH.[229] Artuković was sentenced to death, but the sentence was not carried out due to his age and health.[230] Efraim Zuroff, a Nazi hunter, played a significant role in capturing Dinko Šakić, another the Jasenovac camp commander, during 1990s.[231] After pressure from the international community on the right-wing president Franjo Tuđman, he sought Šakić's extradition and he stood trial in Croatia, aged 78; he was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and given the maximum sentence of 20 years imprisonment. According to the human rights researchers Eric Stover, Victor Peskin and Alexa Koenig it was "the most important post-Cold War domestic effort to hold criminally accountable a Nazi war crimes suspect in a former Eastern European communist country".[231]

Ratlines, terrorism and assassinations[editar | editar código-fonte]

With the Partisan liberation of Yugoslavia, many Ustaše leaders fled and took refuge at the college of San Girolamo degli Illirici near the Vatican.[92] Catholic priest and Ustaše Krunoslav Draganović directed the fugitives from San Girolamo.[92] The US State Department and Counter-Intelligence Corps helped war criminals to escape, and assisted Draganović (who later worked for the American intelligence) in sending Ustaše abroad.[92] Many of those responsible for mass killings in NDH took refuge in South America, Portugal, Spain and the United States.[92] Luburić was assassinated in Spain in 1969 by an UDBA agent; Artuković lived in Ireland and California until extradited in 1986 and died of natural causes in prison; Dinko Šakić and his wife Nada lived in Argentina until extradited in 1998, Dinko dying in prison and his wife released.[92] Draganović also arranged Gestapo functionary Klaus Barbie's flight.[92]

Among some of the Croat diaspora, the Ustaše became heroes.[92] Ustaše émigré terrorist groups in the diaspora (such as Croatian Revolutionary Brotherhood and Croatian National Resistance) carried out assassinations and bombings, and also plane hijackings, throughout the Yugoslav period.[232]

Controversy and denial[editar | editar código-fonte]

Historical revisionism[editar | editar código-fonte]

Some Croats, including politicians, have attempted to minimise the magnitude of the genocide perpetrated against Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia.[233] Historian Mirjana Kasapović concluded that there are three main strategies of historical revisionism in the part of Croatian historiography: the NDH was a normal counter-insurgency state at the time; no mass crimes were committed in the NDH, especially genocide; the Jasenovac camp was just a labor camp, not an extermination camp.[205]

By 1989, the future President of Croatia, Franjo Tuđman had embraced Croatian nationalism and published Horrors of War: Historical Reality and Philosophy, in which he questioned the official number of victims killed by the Ustaše during the Second World War. In his book,Tuđman claimed that between 30,000 and 40,000 died at Jasenovac.[234] Some scholars and observers accused Tuđman of racist statements, “flirting with ideas associated with the Ustaše movement”, appointment of former Ustaše officials to political and military positions, as well as downplaying the number of victims in the Independent State of Croatia.[235][236][237][238][239]

Since 2016, anti-fascist groups, leaders of Croatia's Serb, Roma and Jewish communities and former top Croat officials have boycotted the official state commemoration for the victims of the Jasenovac concentration camp because, as they said, Croatian authorities refused to denounce the Ustaše legacy explicitly and they downplayed and revitalized crimes committed by Ustaše.[240][241][242][243]

Destruction of memorials[editar | editar código-fonte]

After Croatia gained independence, about 3,000 monuments dedicated to the anti-fascist resistance and the victims of fascism were destroyed.[244][245][246] According to Croatian World War II veterans' association, these destructions were not spontaneous, but a planned activity carried out by the ruling party, the state and the church.[244] The status of the Jasenovac Memorial Site was downgraded to the nature park, and parliament cut its funding.[247] In September 1991, Croatian forces entered the memorial site and vandalized the museum building, while exhibitions and documentation were destroyed, damaged and looted.[245] In 1992, FR Yugoslavia sent a formal protest to the United Nations and UNESCO, warning of the devastation of the memorial complex.[245] The European Community Monitor Mission visited the memorial center and confirmed the damage.[245]

Commemoration[editar | editar código-fonte]

Israeli President Moshe Katsav visited Jasenovac in 2003. His successor, Shimon Peres, paid homage to the camp's victims when he visited Jasenovac on 25 July 2010 and laid a wreath at the memorial. Peres dubbed the Ustaše's crimes a "demonstration of sheer sadism".[248][249]

The Jasenovac Memorial Museum reopened in November 2006 with a new exhibition designed by a Croatian architect, Helena Paver Njirić, and an Educational Center, designed by the firm Produkcija. The Memorial Museum features an interior of rubber-clad steel modules, video and projection screens, and glass cases displaying artifacts from the camp. Above the exhibition space, which is quite dark, is a field of glass panels inscribed with the names of the victims.

The New York City Parks Department, the Holocaust Park Committee and the Jasenovac Research Institute, with the help of then-Congressman Anthony Weiner (D-NY), established a public monument to the victims of Jasenovac in April 2005 (the sixtieth anniversary of the liberation of the camps.) The dedication ceremony was attended by ten Yugoslavian Holocaust survivors, as well as diplomats from Serbia, Bosnia and Israel. It remains the only public monument to Jasenovac victims outside the Balkans.

Nowadays, оn 22 April, the anniversary of the prisoner breakout from the Jasenovac camp, Serbia marks the National Holocaust, World War II Genocide and other Fascist Crimes Victims Remembrance Day, while Croatia holds an official commemoration at the Jasenovac Memorial Site.[250] Serbia and Bosnian entity of Republika Srpska hold a joint central commemoration at the Donja Gradina Memorial Zone.[251]

In 2018, an exhibition named “Jasenovac – The Right to Remembrance” was held in the Headquarters of the United Nations in New York City within the marking of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, with the main goal of to foster a culture of remembrance of Serb, Jewish, Roma and anti-fascist victims of the Holocaust and genocide in the Jasenovac camp.[252][253] On 22 April 2020, the president of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić had an official visit to the memorial park in Sremska Mitrovica, dedicated to the victims of genocide on the territory of Syrmia.[254]

Commemoration ceremonies honoring the victims of the Jadovno concentration camp have been organized by the Serb National Council (SNV), the Jewish community in Croatia, and local anti-fascists since 2009, while 24 June has been designated as a "Day of Remembrance of the Jadovno Camp" in Croatia.[251] On 26 August 2010, the 68th anniversary of the partial liberation of the Jastrebarsko children's camp, victims were commemorated in a ceremony at a monument in the Jastrebarsko cemetery. It was attended by only 40 people, mainly members of the Union of Anti-Fascist Fighters and Anti-Fascists of the Republic of Croatia.[255] The Republic of Srpska Government holds a commemoration at the memorial site of the victims of the Ustaše massacres in the Drina Valley.[145]

In culture[editar | editar código-fonte]

Literature[editar | editar código-fonte]

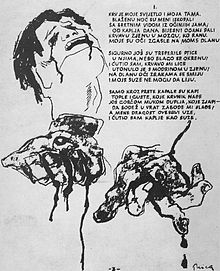

- Jama, a poem condemning the crimes of the Ustaše, written by Ivan Goran Kovačić

- Eagles Fly Early, a novel about children role in assisting the Partisans in the resistance against the Ustaše, written by Branko Ćopić

Art[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Zlatko Prica and Edo Murtić illustrated scenes from the Ivan Goran Kovačić's poem Jama

Theater[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Golubnjača, a play by Jovan Radulović about ethnic relations in neighboring villages in the years after the Ustaše crimes[256]

Films[editar | editar código-fonte]

- 1955 – Šolaja, a film about Serb rebellion against the genocide, directed by Vojislav Nanović

- 1960 – The Ninth Circle, a film directed by France Štiglic, includes scenes from the Jasenovac camp

- 1966 – Eagles Fly Early, film based on the eponymous novel directed by Soja Jovanović

- 1967 – Black Birds, a film about a group of prisoners of Stara Gradiška concentration camp, directed by Eduard Galić

- 1984 – The End of the War, a film about Serbian man takes his son to find and kill members of the Ustaše militia who tortured and killed his wife and mother, directed by Dragan Kresoja

- 1988 – Braća po materi, a film about Ustaše atrocities told through the story of two half-brothers, a Croat and a Serb, directed by Zdravko Šotra

- 2016 – Prva trećina – oproštaj kao kazna, a short feature film about the Žile Friganović's massacres, directed by Svetlana Petrov

- 2019 – The Diary of Diana B., a biographical film about aid operation of Diana Budisavljević for the rescue of more than 10,000 children from concentration camps, directed by Dana Budisavljević

- 2020 – Dara of Jasenovac, a film about a girl who survived the Jasenovac camp, directed by Predrag Antonijević

TV Series[editar | editar código-fonte]

- 1981 – Nepokoreni grad, a TV series about Ustaše terror campaign, including the Kerestinec camp, directed by Vanča Kljaković and Eduard Galić

Music[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Some survivors claim that the lyrics of the famous song "Đurđevdan" was written on a train that took prisoners from Sarajevo to the Jasenovac camp.[257]

- Thompson, a Croatian rock band, has garnered controversy for their purported glorification of Ustashe regime in their songs and concerts, and the most famous such song is "Jasenovac i Gradiška Stara".[258][259]

See also[editar | editar código-fonte]

Annotations[editar | editar código-fonte]

Predefinição:Cnote2 Begin Predefinição:Cnote2 Predefinição:Cnote2 Predefinição:Cnote2 Predefinição:Cnote2 Predefinição:Cnote2 End

Footnotes[editar | editar código-fonte]

- ↑ Jonassohn & Björnson 1998, p. 281, Carmichael & Maguire 2015, p. 151, Tomasevich 2001, p. 347, Mojzes 2011, p. 54, Kallis 2008, pp. 130–132, Suppan 2014, p. 1005 , Fischer 2007, pp. 207–208, Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 187, McCormick 2008

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 347, 404,Yeomans 2015, pp. 265–266, Kallis 2008, pp. 130–132,Fischer 2007, pp. 207–208, Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 187, McCormick 2008, Newman 2017

- ↑ a b c Fischer 2007, p. 207.

- ↑ Jonassohn & Björnson 1998, p. 281.

- ↑ JUŽNOSLAVENSKO PITANJE. Prikaz cjelokupnog pitanja (Die südslawische Frage und der Weltkrieg: Übersichtliche Darstellung des Gesamt-problems). Prevod: Fedor Pucek, Matica hrvatska, Varaždin, 1990

- ↑ Carmichael 2012, p. 97.

- ↑ a b Yeomans 2015, p. 265.

- ↑ Bartulin 2013, p. 37.

- ↑ a b c d e f g McCormick 2008.

- ↑ a b Kenrick 2006, p. 92.

- ↑ Bartulin 2013, p. 123.

- ↑ Yeomans 2015, p. 167.

- ↑ Kallis 2008, pp. 130-132.

- ↑ a b c d e f Newman 2017.

- ↑ a b c Kallis 2008, p. 130.

- ↑ a b c Newman 2014.

- ↑ Suppan 2014, p. 310, 314.

- ↑ Yeomans 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ a b Kallis 2008, pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Bartulin 2013, p. 124.

- ↑ Bartulin 2013, pp. 56-60.

- ↑ Bartulin 2013, pp. 52-53.

- ↑ a b c d e Ramet 2006, p. 118.

- ↑ a b Ognyanova 2000, p. 3.

- ↑ a b Suppan 2014, p. 39, 592.

- ↑ Suppan 2014, p. 591.

- ↑ Yeomans 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ a b c d Yeomans 2015, p. 300.

- ↑ Suppan 2014, p. 586.

- ↑ a b Tomasevich 2001, p. 404.

- ↑ Yeomans 2015, p. 150, 300.

- ↑ Suppan 2014, p. 573, 588-590.

- ↑ «Ustaša». Encyclopædia Britannica. Consultado em 7 May 2020 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Suppan 2014, p. 590.

- ↑ a b Rogel 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ a b Yeomans 2015, p. 150.

- ↑ Mojzes 2011, pp. 52-53.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Levy 2009.

- ↑ Fischer 2007, p. 208.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 402-404.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 403.

- ↑ a b Yeomans 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Pavasović Trošt 2018.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ Suppan 2014, p. 592.

- ↑ Yeomans 2015, p. 301.

- ↑ Kallis 2008, pp. 130, Yeomans 2015, p. 263, Suppan 2014, p. 591, Levy 2009, Domenico & Hanley 2006, p. 435, Adeli 2009, p. 9

- ↑ Kallis 2008, p. 134.

- ↑ a b Payne 2006.

- ↑ Fischer 2007, p. ?.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 272.

- ↑ Kallis 2008, p. 239.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 466.

- ↑ «Deciphering the Balkan Enigma: Using History to Inform Policy» (PDF). Consultado em 3 June 2011 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Mojzes 2011, p. 54.

- ↑ Jones, Adam & Nicholas A. Robins. (2009), Genocides by The Oppressed: Subaltern Genocide In Theory and Practice, p. 106, Indiana University Press; ISBN 978-0-253-22077-6

- ↑ Jacobs 2009, p. 158-159.

- ↑ Adriano & Cingolani 2018, p. 190.

- ↑ Shepherd 2012, p. 78.

- ↑ a b Israeli 2013, p. 45.

- ↑ Goldstein 1999, p. 134.

- ↑ Weiss-Wendt 2010, p. 148.

- ↑ Weiss-Wendt 2010, pp. 148-149, 157.

- ↑ Suppan 2014, pp. 32, 1065.

- ↑ Goldstein 1999, p. 133.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 425.

- ↑ Ognyanova 2000, p. 22.

- ↑ a b Yeomans 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ Fischer 2007, pp. 207–208, 210, 226.

- ↑ Fischer 2007, p. 212.

- ↑ a b Phayer 2000, p. 31.

- ↑ a b Barbier 2017, p. 169.

- ↑ Bloxham & Gerwarth 2011, p. 111.

- ↑ Yeomans 2015, p. 132.

- ↑ Israeli 2013, p. 51.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 312.

- ↑ Levy 2011, p. 61.

- ↑ Fischer 2007, p. 228.

- ↑ a b c d Yeomans 2012, p. 18.

- ↑ Yeomans 2012, p. 2.

- ↑ Levy 2011, p. 69.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 726.

- ↑ Yeomans 2015, p. 21, Pavlowitch 2008, p. 34

- ↑ a b Yeomans 2015, p. 3, Pavlowitch 2008, p. 34

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 132.

- ↑ a b Levy 2011, p. 70.

- ↑ Levy 2011, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Levy 2011, p. 71.

- ↑ Weiss Wendt 2010, p. 147.

- ↑ Lituchy 2006, p. 117.

- ↑ Bulajić 2002, p. 231.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Levy 2011, p. 72.

- ↑ Schindley & Makara 2005, p. 149.

- ↑ Jacobs 2009, p. 160.

- ↑ a b Byford 2014.

- ↑ Lituchy 2006, p. 220.

- ↑ a b «The Extradition of Nazi Criminals: Ryan, Artukovic, and Demjanjuk». Simon Wiesenthal Center. Consultado em 10 May 2020 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Schindley & Makara 2005, p. 42, 393.

- ↑ «Survivor Testimonies» (PDF). Kingsborough Community College. Consultado em 10 May 2020 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Bulajić 2002, p. 7.

- ↑ a b Dulić 2006.

- ↑ Milekic, Sven (6 October 2014). «WWII Children's Concentration Camp Remembered in Croatia». Balkan Insight. Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN). Consultado em 10 May 2020 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=, |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Kolanović, Josip, ed. (2003). Dnevnik Diane Budisavljević 1941–1945. Zagreb: Croatian State Archives and Public Institution Jasenovac Memorial Area. pp. 284–85. ISBN 978-9-536-00562-8

- ↑ Lomović, Boško (2014). Die Heldin aus Innsbruck – Diana Obexer Budisavljević. Belgrade: Svet knjige. p. 28. ISBN 978-86-7396-487-4

- ↑ a b c d Biondich, Mark (2011). The Balkans: Revolution, War, and Political Violence Since 1878. [S.l.]: Oxford University Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0-19929-905-8

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 104.

- ↑ Yeomans 2012, p. vii.

- ↑ Goñi, Uki. The real Odessa: Smuggling the Nazis to Perón's Argentina; Granta, 2002, p. 202. ISBN 9781862075818

- ↑ a b King 2012.

- ↑ a b Cornwell, John (2000). Hitler's Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII. [S.l.]: Penguin. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0-14029-627-3

- ↑ Zatezalo 2005, pp. 228.

- ↑ Zatezalo 2005, pp. 132-136.

- ↑ Zatezalo 2005, p. 79.

- ↑ Bulajić 1988–1989, p. 254.

- ↑ a b Zatezalo 2005, p. 186.

- ↑ Zatezalo 2005, pp. 186-187.

- ↑ Goldstein 2013, p. 127.

- ↑ Goldstein 2013, p. 128.

- ↑ a b Goldstein 2013, p. 129.

- ↑ Singleton, Fred (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. [S.l.]: Cambridge University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-52127-485-2

- ↑ Locke, Hubert G.; Littell, Marcia Sachs (1996). Holocaust and Church Struggle: Religion, Power, and the Politics of Resistance. [S.l.]: University Press of America. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-76180-375-1

- ↑ Zatezalo 2005, p. 286.

- ↑ Zatezalo 2005, p. 304.

- ↑ Zatezalo 1989, p. 180.

- ↑ Perrone 2017.

- ↑ Zatezalo 2005, p. 126.

- ↑ Škiljan 2010.

- ↑ Korb 2010b.

- ↑ Greif 2018, p. 437.

- ↑ Mojzes 2011, p. 75-76.

- ↑ Cvetković 2009, pp. 124-128.

- ↑ Barić 2019.

- ↑ a b Schindley & Makara 2005, p. 362.

- ↑ Bergholz 2012, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Bergholz 2012, p. 76.

- ↑ Goldstein 2013, p. 120.

- ↑ a b Greer & Moberg 2001, p. 142.

- ↑ Dulic, Tomislav (22 November 2011). «Gacko massacre, June 1941». SciencesPo Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ a b Bergholz, Max (2016). Violence as a Generative Force: Identity, Nationalism, and Memory in a Balkan Community. [S.l.]: Cornell University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-501-70643-1

- ↑ a b Bulajić 1992b, p. 56.

- ↑ Bulajić 1988–1989, p. 683.

- ↑ Hoare 2006, pp. 202–203.

- ↑ Yeomans 2011, p. 194.

- ↑ Sokol 2014.

- ↑ a b «Prime Minister Višković attends the commemorating ceremony in memory of the Serbs killed in Stari Brod and Miloševići in 1942». Republic of Srpska Government. Consultado em 12 May 2020 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ a b Balić 2009.

- ↑ Yeomans 2015, p. 24.

- ↑ a b c Škiljan 2012.

- ↑ a b Tomasevich 2001, p. 394.

- ↑ Weiss-Wendt 2010, p. 149.

- ↑ Weiss-Wendt 2010, p. 157.

- ↑ Weiss-Wendt 2010, p. 150.

- ↑ a b Ramet 2006, p. 114.

- ↑ a b c d e Yeomans 2015, p. 178.

- ↑ a b Vuković 2004, p. 431.

- ↑ a b Ramet 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 100.

- ↑ a b Tomasevich 2001, p. 398.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 126.

- ↑ Yeomans 2015, pp. 178-179.

- ↑ Vuković 2004, p. 430.

- ↑ Vuković 2004, p. 430, Rivelli 1999, p. 171

- ↑ Vuković 2004, p. 431, Dakina 1994, p. 209, Simić 1958, p. 139

- ↑ Mojzes 2011, p. 64.

- ↑ Djilas 1991, p. 211.

- ↑ a b c Mojzes 2011, p. 63.

- ↑ Vuković 2004, p. 431, Đurić 1991, p. 127, Djilas 1991, p. 211, Paris 1988, p. 197

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 542.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 529.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 546.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, vol 1, p. 328.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 531.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 537.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 565.

- ↑ a b c Velikonja 2003, p. 170.

- ↑ Bećirović, Denis (2010). «Komunistička vlast i Srpska Pravoslavna Crkva u Bosni i Hercegovini (1945-1955) - Pritisci, napadi, hapšenja i suđenja». Tokovi istorije (3): 78

- ↑ Biondich 2006.

- ↑ Goldstein 2001, pp. 559.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 566.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 563–564.

- ↑ Biondich 2007a, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 555.

- ↑ a b Tomasevich 2001, p. 564.

- ↑ Vuković 2004, p. 432.

- ↑ Goldstein 2001, pp. 559, 578.

- ↑ «Oštre reakcije Srbije: Rehabilitacija ustaške NDH». Al Jazeera Balkans. Consultado em 11 May 2020 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ a b «Jasenovac» (em inglês). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Consultado em 3 June 2020 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 736–737.

- ↑ Kočović 2005, p. XVII.

- ↑ Kočović 2005, p. 113.

- ↑ Žerjavić 1993, p. 10.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 719.

- ↑ Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Volume 2. [S.l.]: Cambridge University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-52127-459-3

- ↑ Ramet, Sabrina P. (1992). Nationalism and Federalism in Yugoslavia, 1962-1991 Second ed. [S.l.]: Indiana University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-25334-794-7.

Pavelić and his Ustaše henchmen alone were responsible for the liquidation of some 350,000 Serbs.

- ↑ Ramet 2007, p. 4.

- ↑ Hoare, Marko Attila (2014). The Bosnian Muslims in the Second World War. [S.l.]: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19936-531-9.

..the Ustasha embarked on a policy of genocide which, in conjunction with the Nazi Holocaust with which it overlapped, claimed the lives of at least 30,000 Jews, a similar number of Gypsies and perhaps nearly 300,000 Serbs.

- ↑ Charny 1999, pp. 27-28.

- ↑ Charny 1999, pp. 18-23.

- ↑ a b Payne 2006, pp. 18-23.

- ↑ Rapaić 1999, Krestić 1998, SANU 1995, Kurdulija 1993, Bulajić 1992, Kljakić 1991

- ↑ McCormick 2014, McCormick 2008, Yeomans 2012, p. 5, Levy 2011, Lemkin 2008, pp. 259–264, Mojzes 2008, p. 154, Rivelli 1999, Paris 1961

- ↑ Samuel Totten; William S. Parsons (2004). Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. [S.l.]: Routledge. p. 422. ISBN 978-1-135-94558-9.

The Independent State of Croatia willingly cooperated with the Nazi “Final Solution” against Jews and Gypsies, but went beyond it, launching a campaign of genocide against Serbs in “greater Croatia.” The Ustasha, like the Nazis whom they emulated, established concentration camps and death camps.

- ↑ Michael Lees (1992). The Serbian Genocide 1941–1945. [S.l.]: Serbian Orthodox Diocese of Western America

- ↑ John Pollard (30 October 2014). The Papacy in the Age of Totalitarianism, 1914–1958. [S.l.]: OUP Oxford. pp. 407–. ISBN 978-0-19-102658-4 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ a b c Kasapović 2018.

- ↑ «Ustasa» (PDF). Yad Vashem. Consultado em 25 June 2018 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ «Croatian President Mesic Apologizes for Croatian Crimes Against the Jews during the Holocaust». Yad Vashem