Usuário:Gato Preto/Testes/7

O ácido ribonucleico (ARN, em português: ácido ribonucleico; ou RNA, em inglês: ribonucleic acid) é um composto orgânico cujas moléculas contêm as instruções genéticas que controlam a codificação genética, a descodificação genética durante a tradução de proteínas, a sintetização das mesmas e a regulação e expressão dos genes. O ARN e o ADN são ácidos nucleicos e, juntamente com os lípidos, as proteínas e os glícidos, constituem as quatro maiores macromoléculas essenciais de todas as formas conhecidas de vida.

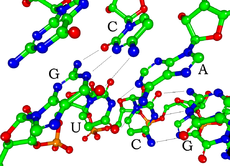

Do ponto de vista químico, o ARN é um longo polímero de unidades simples (monómeros) de nucleótidos, cuja cadeia principal é formada por moléculas de açúcares e fosfato intercalados unidos por ligações fosfodiéster. Ligada à molécula de açúcar está uma de quatro bases nitrogenadas. A sequência de bases ao longo da molécula de ARN constitui a informação genética. O ARN, ao contrário do ADN que forma uma dupla hélice bicatenária; é maioritariamente monocatenário, contudo, pode dobrar-se sobre si próprio. Os organismos celulares usam o ARN mensageiro (ARNm) para transportar a informação genética (usando as bases nitrogenadas guanina, uracilo, adenina e citosina; representadas pela letras G, U, A e C, respectivamente) que controla a síntese de proteínas específicas. Muitos vírus codificam a sua informação genética usando um genoma de ARN.

Algumas moléculas de ARN têm um papel activo nas células catalizando reacções biológicas, controlando a expressão dos genes ou sinalizando e transportando respostas a sinais celulares. Um destes processos activos é a síntese de proteínas, uma função universal na qual as moléculas de ARN controlam a sintetização de proteínas nos ribossomas. Este processo usa as moléculas do ARN transportador (ARNt) para levar aminoácidos para o ribossoma, onde o ARN ribossómico (ARNr) liga aminoácidos para formar proteínas.

Comparação com o ADN[editar | editar código-fonte]

A estrutura química do ARN é muito semelhante à do ADN, mas difere em três aspectos principais:

- Ao contrário da dupla hélice bicatenária do ADN, o ARN é uma molécula monocatenária[1] em muitas actividades biológicas suas e consiste duma cadeia mais curta de nucleótidos.[2] Porém, o ARN pode, por junção de pares de base complementares, formar hélices duplas, como por exemplo no ARNt.

- Enquanto a "coluna vertebral" açúcar-fosfato do ADN contém desoxirribose, o ARN contém a ribose.[3] A ribose tem um hidroxilo aderido ao anel de pentose na posição 2', a desoxirribose não tem este hidroxilo. Os grupos hidroxilo na coluna da ribosa torna o ARN menos estável que o ADN porque isto aumenta a sua propensão à hidrólise.

- A base complementar da adenina no ADN é a timina; no ARN, no entanto, é o uracilo, o qual é uma forma desmetilada da timina.[4]

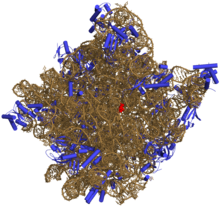

Tal como o ADN, a maioria dos ARN biológicos activos, incluindo o ARNm, o ARNt, o ARNt, os ARNnp e outros ARNs não-codificantes, contêm sequências auto-complementares que permitem o dobramento de secções do ARN[5] e unir-se a si próprio para formar hélices duplas. As análises destes ARNs revela que estão altamente estruturados. Ao invés do ADN, as suas estruturas não consistem de longas hélices duplas, mas de colecções de pequenas hélices agrupadas em estruturas afins à proteínas. Da mesma maneira, os ARNs podem alcançar a catálise química (como as enzimas).[6] A determinação da estrutura dos ribossomas, um orgânulo de ARN proteicoque cataliza a formação de ligações de peptídios, revelou que o seu espaço activo está composto inteiramente por ARN.[7]

Estrutura[editar | editar código-fonte]

Cada nucleótido no ARN contém um açúcar de ribose, com carbonos de 1' até 5'. A base está aderida à posição 1', em geral, a adenina (A), a citosina (C), a guanina e o uracilo (U). A adenina e a guanina são purinas, a citocisina e o uracilo são pirimidinas. Um fosfato estã grudado na posição 3' duma ribose e o 5' na posição seguinte. Os fosfatos têm uma carga negativa, tornando o ARN uma molécula carregada (poli-anião). A bases forman pontes de hidrogéneo entre a citosina e a guanina, entre a adenina e o uracilo e entre a guanina e o uracilo.[8] Porém, outras interacções são possíveis, tais como um grupo de bases de adenina ligam-se en forma de bojo,[9] ou o tetraciclo GNRA que tem pares de base guanina–adenina.[8]

Um componente estrutural importante do ARN que o diferencia do ADN é a presença dum hidroxilo na posição 2' do açúcar ribose. A presença do hidroxilo faz com que a hélice adopta principalmente uma geometria A.[10] Contudo, em contexto duma só hélice com dous nucleótidos, o ARN pode, embora raramente, adoptar a forma B mais comummente observada no ADN.[11] A geometria A resulta num sulco profundo e estreito e noutro superficial e folgado.[12] Outra consequência da presença do hidroxilo na posição 2' é que em secções flexíveis duma molécula de ARN (isto é, não envolvidas na formação duma hélice dupla), pode atacar químicamente a ligação fosfodiéster adjacente para fender a coluna.[13]

O ARN é transcrito somente com quatro bases nitrogenadas (a adenina, a citosina, a guanina e o uracilo).[14] Porém, esta bases e açúcares apensados podem ser modificados de várias maneiras acompanhando a maturação do ARN. A pseudouridina (Ψ), na qual a ligação entre o uracilo e a ribose deixa de ser uma ligação C-N para ser C-C e a ribotimidina (T) são achadas em vários lugares (os mais notáveis sendo o ciclo TΨC do ARNt).[15] Outra importante base modificada importante é a hipoxantina, uma forma desaminada da adenina cujos nucleosídeos são feitos de inosina (I). A inosina tem um papel chave no emparelhamento wobble do código genético.[16]

Há mais de cem nucleosídeos modificados que ocorrem naturalmente.[17] A maior diversidade de modificações é achada no ARNt,[18] embora a pseudouridina e os nucleosídeos com 2'-O-metilação presente no ARNr são os mais comuns.[19] O papel específico de muitas destas modificações no ARN não são totalmente percebidas. Porém, é importante destacar o facto de que, no ARN ribossómico, muitas das modificações post-transcripcionais ocorrem em regiões altamente funcionais, tais como o centro da peptidil transferase e na interface de subunidade; tudo isto indica que são importantes para o funcionamento normal organular e celular.[20]

A forma funcional das moléculas duma só hélice do ARN, tal como as proteínas, costuma depender também uma estrutura terciária específica. A armação necessária para a existência desta estrutura é fornecida por elementos da estrutura secundária, constituídos por ligações de hidrogéneo com a molécula. Esto leva à classifcação de vários "domínios" diferenciáveis da estrutura secundária como os hairpin loops, os bojos e os internal loops.[21] Dado que o ARN tem carga, os iões metálicos como o Mg2+ são precisos para estabilizar muitas estruturas secundárias e terciárias.[22]

O enantiómero de origen natural do ARN é o D-RNA composto por D-ribonucleótidos. Todos os centros quirais estão na D-ribose. Devido ao uso de L-ribose ou até L-ribonucleótides, o L-RNA pode ser sintetizado. O L-RNA é muito mais estável perante a degradação da ribonuclease (RNase).[23]

Tal como a estrutura de biopolímeros como as proteínas, é possível definir a topologia duma molécula dobrada de ARN. Isto costuma ser feito com contactos intra-cadeias dentro do ARN embrulhado; esta técnica é conhecida como topologia de circuito.

Síntese[editar | editar código-fonte]

Synthesis of RNA is usually catalyzed by an enzyme—RNA polymerase—using DNA as a template, a process known as transcription. Initiation of transcription begins with the binding of the enzyme to a promoter sequence in the DNA (usually found "upstream" of a gene). The DNA double helix is unwound by the helicase activity of the enzyme. The enzyme then progresses along the template strand in the 3’ to 5’ direction, synthesizing a complementary RNA molecule with elongation occurring in the 5’ to 3’ direction. The DNA sequence also dictates where termination of RNA synthesis will occur.[24]

Primary transcript RNAs are often modified by enzymes after transcription. For example, a poly(A) tail and a 5' cap are added to eukaryotic pre-mRNA and introns are removed by the spliceosome.

There are also a number of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases that use RNA as their template for synthesis of a new strand of RNA. For instance, a number of RNA viruses (such as poliovirus) use this type of enzyme to replicate their genetic material.[25] Also, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is part of the RNA interference pathway in many organisms.[26]

Tipos de ARN[editar | editar código-fonte]

Visão geral[editar | editar código-fonte]

Messenger RNA (mRNA) is the RNA that carries information from DNA to the ribosome, the sites of protein synthesis (translation) in the cell. The coding sequence of the mRNA determines the amino acid sequence in the protein that is produced.[27] However, many RNAs do not code for protein (about 97% of the transcriptional output is non-protein-coding in eukaryotes[28][29][30][31]).

These so-called non-coding RNAs ("ncRNA") can be encoded by their own genes (RNA genes), but can also derive from mRNA introns.[32] The most prominent examples of non-coding RNAs are transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA), both of which are involved in the process of translation.[4] There are also non-coding RNAs involved in gene regulation, RNA processing and other roles. Certain RNAs are able to catalyse chemical reactions such as cutting and ligating other RNA molecules,[33] and the catalysis of peptide bond formation in the ribosome;[7] these are known as ribozymes.

No comprimento[editar | editar código-fonte]

Dependendo do comprimento da cadeia de ARN, o ARN inclui o pequeno ARN e o ARN longo.[34] Geralmente, os pequenos ARNs são menores de duzentos nucleótidos em comprimento e os ARNs longos são maiores do que duzentos.[35] O ARN longo inclui, principalmente, o ARN longo não-codificante (IncRNA) e o ARNm. O pequeno ARN inclui, principalmente, o ARN ribossómico (ARNr) 5.8S, o ARNr 5S, o ARN transportador (ARNt), o microARN (miRNA), o siRNA, o SnoRNA, o piRNA, o tsRNA[36] e o srRNA).[37]

Na tradução[editar | editar código-fonte]

Messenger RNA (mRNA) carries information about a protein sequence to the ribosomes, the protein synthesis factories in the cell. It is coded so that every three nucleotides (a codon) corresponds to one amino acid. In eukaryotic cells, once precursor mRNA (pre-mRNA) has been transcribed from DNA, it is processed to mature mRNA. This removes its introns—non-coding sections of the pre-mRNA. The mRNA is then exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where it is bound to ribosomes and translated into its corresponding protein form with the help of tRNA. In prokaryotic cells, which do not have nucleus and cytoplasm compartments, mRNA can bind to ribosomes while it is being transcribed from DNA. After a certain amount of time, the message degrades into its component nucleotides with the assistance of ribonucleases.[27]

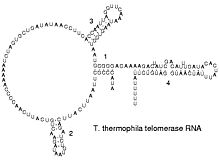

Transfer RNA (tRNA) is a small RNA chain of about 80 nucleotides that transfers a specific amino acid to a growing polypeptide chain at the ribosomal site of protein synthesis during translation. It has sites for amino acid attachment and an anticodon region for codon recognition that binds to a specific sequence on the messenger RNA chain through hydrogen bonding.[32]

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is the catalytic component of the ribosomes. Eukaryotic ribosomes contain four different rRNA molecules: 18S, 5.8S, 28S and 5S rRNA. Three of the rRNA molecules are synthesized in the nucleolus, and one is synthesized elsewhere. In the cytoplasm, ribosomal RNA and protein combine to form a nucleoprotein called a ribosome. The ribosome binds mRNA and carries out protein synthesis. Several ribosomes may be attached to a single mRNA at any time.[27] Nearly all the RNA found in a typical eukaryotic cell is rRNA.

Transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA) is found in many bacteria and plastids. It tags proteins encoded by mRNAs that lack stop codons for degradation and prevents the ribosome from stalling.[38]

ARNs interferentes[editar | editar código-fonte]

Several types of RNA can downregulate gene expression by being complementary to a part of an mRNA or a gene's DNA.[39][40] MicroRNAs (miRNA; 21-22 nt) are found in eukaryotes and act through RNA interference (RNAi), where an effector complex of miRNA and enzymes can cleave complementary mRNA, block the mRNA from being translated, or accelerate its degradation.[41][42]

While small interfering RNAs (siRNA; 20-25 nt) are often produced by breakdown of viral RNA, there are also endogenous sources of siRNAs.[43][44] siRNAs act through RNA interference in a fashion similar to miRNAs. Some miRNAs and siRNAs can cause genes they target to be methylated, thereby decreasing or increasing transcription of those genes.[45][46][47] Animals have Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNA; 29-30 nt) that are active in germline cells and are thought to be a defense against transposons and play a role in gametogenesis.[48][49]

Many prokaryotes have CRISPR RNAs, a regulatory system similar to RNA interference.[50] Antisense RNAs are widespread; most downregulate a gene, but a few are activators of transcription.[51] One way antisense RNA can act is by binding to an mRNA, forming double-stranded RNA that is enzymatically degraded.[52] There are many long noncoding RNAs that regulate genes in eukaryotes,[53] one such RNA is Xist, which coats one X chromosome in female mammals and inactivates it.[54]

An mRNA may contain regulatory elements itself, such as riboswitches, in the 5' untranslated region or 3' untranslated region; these cis-regulatory elements regulate the activity of that mRNA.[55] The untranslated regions can also contain elements that regulate other genes.[56]

No processamento do ARN[editar | editar código-fonte]

Many RNAs are involved in modifying other RNAs. Introns are spliced out of pre-mRNA by spliceosomes, which contain several small nuclear RNAs (snRNA),[4] or the introns can be ribozymes that are spliced by themselves.[57] RNA can also be altered by having its nucleotides modified to nucleotides other than A, C, G and U. In eukaryotes, modifications of RNA nucleotides are in general directed by small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNA; 60–300 nt),[32] found in the nucleolus and cajal bodies. snoRNAs associate with enzymes and guide them to a spot on an RNA by basepairing to that RNA. These enzymes then perform the nucleotide modification. rRNAs and tRNAs are extensively modified, but snRNAs and mRNAs can also be the target of base modification.[58][59] RNA can also be methylated.[60][61]

Genoma de ARN[editar | editar código-fonte]

Like DNA, RNA can carry genetic information. RNA viruses have genomes composed of RNA that encodes a number of proteins. The viral genome is replicated by some of those proteins, while other proteins protect the genome as the virus particle moves to a new host cell. Viroids are another group of pathogens, but they consist only of RNA, do not encode any protein and are replicated by a host plant cell's polymerase.[62]

Na transcrição reversa[editar | editar código-fonte]

Reverse transcribing viruses replicate their genomes by reverse transcribing DNA copies from their RNA; these DNA copies are then transcribed to new RNA. Retrotransposons also spread by copying DNA and RNA from one another,[63] and telomerase contains an RNA that is used as template for building the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes.[64]

ARN de duas hélices[editar | editar código-fonte]

Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is RNA with two complementary strands, similar to the DNA found in all cells. dsRNA forms the genetic material of some viruses (double-stranded RNA viruses). Double-stranded RNA such as viral RNA or siRNA can trigger RNA interference in eukaryotes, as well as interferon response in vertebrates.[65][66][67][68]

ARN circular[editar | editar código-fonte]

In the late 1970s, it was shown that there is a single stranded covalently closed, i.e. circular form of RNA expressed throughout the animal and plant kingdom (see circRNA).[69] circRNAs are thought to arise via a "back-splice" reaction where the spliceosome joins a downstream donor to an upstream acceptor splice site. So far the function of circRNAs is largely unknown, although for few examples a microRNA sponging activity has been demonstrated.

Descobrimentos chave na biologia do ARN[editar | editar código-fonte]

A pesquisa no ARN tem levado a descobertas muito importantes no campo da biologia e numerosos laureados Nobel. Os ácidos nucleicos foram descobertos em 1868 por Friederich Miescher quem os chamou nucleína dado que era achada no núcleo.[70] Posteriormente foi descoberto que as células procariontes, que não têm núcleo, também contêm ácidos nucleicos. O papel do ARN na síntese de proteínas já era conjeturada em 1939.[71] Severo Ochoa recebeu o Prémio Nobel de Fisiologia ou Medicina de 1959 (partilhado com Arthur Kornberg) após ter descoberto uma enzima que era capaz de sintetizar o ARN no laboratório.[72] Porém, a enzima descoberta por Ochoa (polinucleótido fosforilase) não estara implicada na síntese do ARN, mas na sua degradação. Em 1956 Alex Rich e David Davies hibridizaram duas cadeias de ARN para formar o primeiro cristal de ARN cuja estrutura podia ser determinada por uma cristalografia de raios X.[73]

A sequência do ARNt de setenta e sete nucleóditos duma levedura foi achada por Robert W. Holley em 1965,[74] achado pelo qual foi galardoado com o Prémio Nobel de Fisiologia ou Medicina de 1968 (partilhado com Har Gobind Khorana e Marshall Nirenberg).[75]

No começo da década de 1970, os retrovírus e a transcriptase reversa foram descobertos, mostrando por primeira vez que as enzimas eram capazes de tornar o ARN em ADN (o oposto do ciclo consuetudinário da transmissão da informação genética). Por este trabalho, David Baltimore, Renato Dulbecco e Howard M.Temin foram laureados com o Prémio Nobel de Fisiologia ou Medicina em 1975.[76] Em 1976, Walter Fiers e a sua equipa determinaram a primeira sequência completa de nucleótidos do genoma dum vírus ARN, o do bacteriófago MS2.[77]

Em 1977, os intrões e o splicing do ARN foram achados tanto no vírus dos mamíferos e nos genes celulares, resultando na outorgação do Prémio Nobel de Fisiologia ou Medicina de 1993 para Philip Sharp e Richard Roberts.[78] As moléculas catalíticas do ARN (os ribossomas) foram descobertas no começo da década de 1980, levando à laureação do Prémio Nobel de Química de 1989 para Thomas Cech e Sidney Altman.[79] Em 1990, achou-se nas Petunia que genes introduzidos podem silenciar genes próprios análogos da planta, agora sabe-se que é devido ao ARN interferente.[80][81]

Por volta da mesma altura, vinte e dous nucleótidos de ARN, agora chamados micro-ARN, foram relacionados com o desenvolvimento da Caenorhabditis elegans.[82] Os estudos no ARN inferente levaram à concessão do Prémio Nobel de Fisiologia ou Medicina de 2006 para Andrew Fire and Craig Mello,[83] e a concessão do Prémio Nobel de Química desse mesmo ano para Roger Kornberg.[84] A descoberta do ARN regulador de genes, tem iniciado a investigação de possíveis fármacos feitos de ARN, tais como o siRNA, para silenciar os genes.[85]

Importância para a química pré-biótica e para a abiogénese[editar | editar código-fonte]

Em 1967, Carl Woese teorizou que o ARN pode ser catalítico e sugeriu que as primeiras formas de vida (moléculas autorreplicantes) podem ter usado o ARN tanto para transportar a transmitir a informação genética como para catalizar reacções bioquímicas, constituindo a hipótese do mundo de ARN.[86][87]

Em Março de 2015, vários nucleótidos complexos de ADN e ARN, incluindo a citosina, o uracilo e a timina, foram alegadamente formados em laboratório sob condições típicas do espaço sideral, usando precursores químicos, tais como a pirimidina, um composto orgânico comummente achado em meteoritos. A pirimidina, tal como os hidrocarbonetos aromáticos policíclicos (HAPs), é um dos compostos ricos em carbono mais abundantes no Universo e podem ter-se formado em gigantes vermelhas ou nas nuvens interestelares.[88]

Ver também[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Origâmi do ARN

- Estrutura biomolecular

- Macromolécula

- ADN

- História da biologia do ARN

- Lista de biólogos do ARN

- Transcriptoma

Referências[editar | editar código-fonte]

- ↑ «Basic Genetics». learn.genetics.utah.edu. Consultado em 27 de abril de 2018

- ↑ «Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids» (PDF). University of California, Los Angeles. Consultado em 27 de abril de 2018

- ↑ Shukla, R. N. (30 de junho de 2014). Analysis Of Chromosome (em inglês). [S.l.]: Agrotech Press. ISBN 9789384568177

- ↑ a b c Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L (2002). Biochemistry 5th ed. [S.l.]: WH Freeman and Company. pp. 118–19, 781–808. ISBN 0-7167-4684-0. OCLC 179705944

- ↑ Tinoco I & Bustamante C (outubro de 1999). «How RNA folds». Journal of Molecular Biology. 293 (2): 271–81. PMID 10550208. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3001.

- ↑ Higgs PG (agosto de 2000). «RNA secondary structure: physical and computational aspects». Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 33 (3): 199–253. PMID 11191843. doi:10.1017/S0033583500003620

- ↑ a b Nissen P, Hansen J, Ban N, Moore PB, Steitz TA (agosto de 2000). «The structural basis of ribosome activity in peptide bond synthesis». Science. 289 (5481): 920–30. Bibcode:2000Sci...289..920N. PMID 10937990. doi:10.1126/science.289.5481.920

- ↑ a b Lee JC, Gutell RR (dezembro de 2004). «Diversity of base-pair conformations and their occurrence in rRNA structure and RNA structural motifs». Journal of Molecular Biology. 344 (5): 1225–49. PMID 15561141. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.072

- ↑ Barciszewski J, Frederic B, Clark C (1999). RNA biochemistry and biotechnology. [S.l.]: Springer. pp. 73–87. ISBN 0-7923-5862-7. OCLC 52403776

- ↑ Salazar M, Fedoroff OY, Miller JM, Ribeiro NS, Reid BR (abril de 1993). «The DNA strand in DNA.RNA hybrid duplexes is neither B-form nor A-form in solution». Biochemistry. 32 (16): 4207–15. PMID 7682844. doi:10.1021/bi00067a007

- ↑ Sedova A, Banavali NK (outubro de 2015). «RNA approaches the B-form in stacked single strand dinucleotide contexts». Biopolymers. 105 (2): 65–82. PMID 26443416. doi:10.1002/bip.22750

- ↑ Hermann T, Patel DJ (março de 2000). «RNA bulges as architectural and recognition motifs». Structure. 8 (3): R47–54. PMID 10745015. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00110-6

- ↑ Mikkola S, Stenman E, Nurmi K, Yousefi-Salakdeh E, Strömberg R, Lönnberg H (1999). «The mechanism of the metal ion promoted cleavage of RNA phosphodiester bonds involves a general acid catalysis by the metal aquo ion on the departure of the leaving group». Perkin transactions 2 (8): 1619–26. doi:10.1039/a903691a

- ↑ Jankowski JA, Polak JM (1996). Clinical gene analysis and manipulation: Tools, techniques and troubleshooting. [S.l.]: Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-521-47896-0. OCLC 33838261

- ↑ Yu Q, Morrow CD (maio de 2001). «Identification of critical elements in the tRNA acceptor stem and T(Psi)C loop necessary for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity». Journal of Virology. 75 (10): 4902–6. PMC 114245

. PMID 11312362. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.10.4902-4906.2001

. PMID 11312362. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.10.4902-4906.2001

- ↑ Elliott MS, Trewyn RW (fevereiro de 1984). «Inosine biosynthesis in transfer RNA by an enzymatic insertion of hypoxanthine». The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 259 (4): 2407–10. PMID 6365911

- ↑ Cantara WA, Crain PF, Rozenski J, McCloskey JA, Harris KA, Zhang X, Vendeix FA, Fabris D, Agris PF (janeiro de 2011). «The RNA Modification Database, RNAMDB: 2011 update». Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (Database issue): D195–201. PMC 3013656

. PMID 21071406. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1028

. PMID 21071406. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1028

- ↑ Söll D, RajBhandary U (1995). TRNA: Structure, biosynthesis, and function. [S.l.]: ASM Press. p. 165. ISBN 1-55581-073-X. OCLC 183036381

- ↑ Kiss T (julho de 2001). «Small nucleolar RNA-guided post-transcriptional modification of cellular RNAs». The EMBO Journal. 20 (14): 3617–22. PMC 125535

. PMID 11447102. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.14.3617

. PMID 11447102. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.14.3617

- ↑ King TH, Liu B, McCully RR, Fournier MJ (fevereiro de 2003). «Ribosome structure and activity are altered in cells lacking snoRNPs that form pseudouridines in the peptidyl transferase center». Molecular Cell. 11 (2): 425–35. PMID 12620230. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00040-6

- ↑ Mathews DH, Disney MD, Childs JL, Schroeder SJ, Zuker M, Turner DH (maio de 2004). «Incorporating chemical modification constraints into a dynamic programming algorithm for prediction of RNA secondary structure». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (19): 7287–92. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.7287M. PMC 409911

. PMID 15123812. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401799101

. PMID 15123812. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401799101

- ↑ Tan ZJ, Chen SJ (julho de 2008). «Salt dependence of nucleic acid hairpin stability». Biophysical Journal. 95 (2): 738–52. Bibcode:2008BpJ....95..738T. PMC 2440479

. PMID 18424500. doi:10.1529/biophysj.108.131524

. PMID 18424500. doi:10.1529/biophysj.108.131524

- ↑ Vater A, Klussmann S (janeiro de 2015). «Turning mirror-image oligonucleotides into drugs: the evolution of Spiegelmer(®) therapeutics». Drug Discovery Today. 20 (1): 147–55. PMID 25236655. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2014.09.004

- ↑ Nudler E, Gottesman ME (August 2002). «Transcription termination and anti-termination in E. coli». Genes to Cells. 7 (8): 755–68. PMID 12167155. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00563.x Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Hansen JL, Long AM, Schultz SC (August 1997). «Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of poliovirus». Structure. 5 (8): 1109–22. PMID 9309225. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(97)00261-X Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Ahlquist P (May 2002). «RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, viruses, and RNA silencing». Science. 296 (5571): 1270–3. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1270A. PMID 12016304. doi:10.1126/science.1069132 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ a b c Cooper GC, Hausman RE (2004). The Cell: A Molecular Approach 3rd ed. [S.l.]: Sinauer. pp. 261–76, 297, 339–44. ISBN 0-87893-214-3. OCLC 174924833

- ↑ Mattick JS, Gagen MJ (September 2001). «The evolution of controlled multitasked gene networks: the role of introns and other noncoding RNAs in the development of complex organisms». Molecular Biology and Evolution. 18 (9): 1611–30. PMID 11504843. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003951 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Mattick JS (November 2001). «Non-coding RNAs: the architects of eukaryotic complexity». EMBO Reports. 2 (11): 986–91. PMC 1084129

. PMID 11713189. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve230 Verifique data em:

. PMID 11713189. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve230 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Mattick JS (October 2003). «Challenging the dogma: the hidden layer of non-protein-coding RNAs in complex organisms» (PDF). BioEssays. 25 (10): 930–9. PMID 14505360. doi:10.1002/bies.10332. Arquivado do original (PDF) em 6 de março de 2009 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Mattick JS (October 2004). «The hidden genetic program of complex organisms». Scientific American. 291 (4): 60–7. PMID 15487671. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1004-60 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda)[ligação inativa] - ↑ a b c Wirta W (2006). Mining the transcriptome – methods and applications. Stockholm: School of Biotechnology, Royal Institute of Technology. ISBN 91-7178-436-5. OCLC 185406288

- ↑ Rossi JJ (July 2004). «Ribozyme diagnostics comes of age». Chemistry & Biology. 11 (7): 894–5. PMID 15271347. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.07.002 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Storz G (maio de 2002). «An expanding universe of noncoding RNAs». Science. 296 (5571): 1260–3. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1260S. PMID 12016301. doi:10.1126/science.1072249

- ↑ Fatica A, Bozzoni I (janeiro de 2014). «Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development». Nature Reviews. Genetics. 15 (1): 7–21. PMID 24296535. doi:10.1038/nrg3606

- ↑ Chen Q, Yan M, Cao Z, Li X, Zhang Y, Shi J, et al. (janeiro de 2016). «Sperm tsRNAs contribute to intergenerational inheritance of an acquired metabolic disorder». Science. 351 (6271): 397–400. Bibcode:2016Sci...351..397C. PMID 26721680. doi:10.1126/science.aad7977

- ↑ Wei H, Zhou B, Zhang F, Tu Y, Hu Y, Zhang B, Zhai Q (2013). «Profiling and identification of small rDNA-derived RNAs and their potential biological functions». PLOS One. 8 (2): e56842. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...856842W. PMC 3572043

. PMID 23418607. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056842

. PMID 23418607. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056842

- ↑ Gueneau de Novoa P, Williams KP (January 2004). «The tmRNA website: reductive evolution of tmRNA in plastids and other endosymbionts». Nucleic Acids Research. 32 (Database issue): D104–8. PMC 308836

. PMID 14681369. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh102 Verifique data em:

. PMID 14681369. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh102 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ (February 2009). «Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs». Cell. 136 (4): 642–55. PMC 2675692

. PMID 19239886. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035 Verifique data em:

. PMID 19239886. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Liang KH, Yeh CT (May 2013). «A gene expression restriction network mediated by sense and antisense Alu sequences located on protein-coding messenger RNAs». BMC Genomics. 14. 325 páginas. PMC 3655826

. PMID 23663499. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-325 Verifique data em:

. PMID 23663499. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-325 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Wu L, Belasco JG (January 2008). «Let me count the ways: mechanisms of gene regulation by miRNAs and siRNAs». Molecular Cell. 29 (1): 1–7. PMID 18206964. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.010 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Matzke MA, Matzke AJ (May 2004). «Planting the seeds of a new paradigm». PLoS Biology. 2 (5): E133. PMC 406394

. PMID 15138502. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020133 Verifique data em:

. PMID 15138502. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020133 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Vazquez F, Vaucheret H, Rajagopalan R, Lepers C, Gasciolli V, Mallory AC, Hilbert JL, Bartel DP, Crété P (October 2004). «Endogenous trans-acting siRNAs regulate the accumulation of Arabidopsis mRNAs». Molecular Cell. 16 (1): 69–79. PMID 15469823. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.028 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Watanabe T, Totoki Y, Toyoda A, et al. (May 2008). «Endogenous siRNAs from naturally formed dsRNAs regulate transcripts in mouse oocytes». Nature. 453 (7194): 539–43. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..539W. PMID 18404146. doi:10.1038/nature06908 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW (July 2005). «Silence from within: endogenous siRNAs and miRNAs». Cell. 122 (1): 9–12. PMID 16009127. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.030 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Doran G (2007). «RNAi – Is one suffix sufficient?». Journal of RNAi and Gene Silencing. 3 (1): 217–19. Arquivado do original em 16 de julho de 2007

- ↑ Pushparaj PN, Aarthi JJ, Kumar SD, Manikandan J (January 2008). «RNAi and RNAa--the yin and yang of RNAome». Bioinformation. 2 (6): 235–7. PMC 2258431

. PMID 18317570. doi:10.6026/97320630002235 Verifique data em:

. PMID 18317570. doi:10.6026/97320630002235 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Horwich MD, Li C, Matranga C, Vagin V, Farley G, Wang P, Zamore PD (July 2007). «The Drosophila RNA methyltransferase, DmHen1, modifies germline piRNAs and single-stranded siRNAs in RISC». Current Biology. 17 (14): 1265–72. PMID 17604629. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.030 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Girard A, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Carmell MA (July 2006). «A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins». Nature. 442 (7099): 199–202. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..199G. PMID 16751776. doi:10.1038/nature04917 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Horvath P, Barrangou R (January 2010). «CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea». Science. 327 (5962): 167–70. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..167H. PMID 20056882. doi:10.1126/science.1179555 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Wagner EG, Altuvia S, Romby P (2002). «Antisense RNAs in bacteria and their genetic elements». Advances in Genetics. Advances in Genetics. 46: 361–98. ISBN 9780120176465. PMID 11931231. doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(02)46013-0

- ↑ Gilbert SF (2003). Developmental Biology 7th ed. [S.l.]: Sinauer. pp. 101–3. ISBN 0-87893-258-5. OCLC 154656422

- ↑ Amaral PP, Mattick JS (August 2008). «Noncoding RNA in development». Mammalian Genome. 19 (7–8): 454–92. PMID 18839252. doi:10.1007/s00335-008-9136-7 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Heard E, Mongelard F, Arnaud D, Chureau C, Vourc'h C, Avner P (June 1999). «Human XIST yeast artificial chromosome transgenes show partial X inactivation center function in mouse embryonic stem cells». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (12): 6841–6. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.6841H. PMC 22003

. PMID 10359800. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.12.6841 Verifique data em:

. PMID 10359800. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.12.6841 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Batey RT (June 2006). «Structures of regulatory elements in mRNAs». Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 16 (3): 299–306. PMID 16707260. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.001 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Scotto L, Assoian RK (June 1993). «A GC-rich domain with bifunctional effects on mRNA and protein levels: implications for control of transforming growth factor beta 1 expression». Molecular and Cellular Biology. 13 (6): 3588–97. PMC 359828

. PMID 8497272 Verifique data em:

. PMID 8497272 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Steitz TA, Steitz JA (July 1993). «A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (14): 6498–502. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.6498S. PMC 46959

. PMID 8341661. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498 Verifique data em:

. PMID 8341661. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Xie J, Zhang M, Zhou T, Hua X, Tang L, Wu W (January 2007). «Sno/scaRNAbase: a curated database for small nucleolar RNAs and cajal body-specific RNAs». Nucleic Acids Research. 35 (Database issue): D183–7. PMC 1669756

. PMID 17099227. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl873 Verifique data em:

. PMID 17099227. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl873 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Omer AD, Ziesche S, Decatur WA, Fournier MJ, Dennis PP (May 2003). «RNA-modifying machines in archaea». Molecular Microbiology. 48 (3): 617–29. PMID 12694609. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03483.x Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Cavaillé J, Nicoloso M, Bachellerie JP (October 1996). «Targeted ribose methylation of RNA in vivo directed by tailored antisense RNA guides». Nature. 383 (6602): 732–5. Bibcode:1996Natur.383..732C. PMID 8878486. doi:10.1038/383732a0 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Kiss-László Z, Henry Y, Bachellerie JP, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Kiss T (June 1996). «Site-specific ribose methylation of preribosomal RNA: a novel function for small nucleolar RNAs». Cell. 85 (7): 1077–88. PMID 8674114. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81308-2 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Daròs JA, Elena SF, Flores R (June 2006). «Viroids: an Ariadne's thread into the RNA labyrinth». EMBO Reports. 7 (6): 593–8. PMC 1479586

. PMID 16741503. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400706 Verifique data em:

. PMID 16741503. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400706 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Kalendar R, Vicient CM, Peleg O, Anamthawat-Jonsson K, Bolshoy A, Schulman AH (March 2004). «Large retrotransposon derivatives: abundant, conserved but nonautonomous retroelements of barley and related genomes». Genetics. 166 (3): 1437–50. PMC 1470764

. PMID 15082561. doi:10.1534/genetics.166.3.1437 Verifique data em:

. PMID 15082561. doi:10.1534/genetics.166.3.1437 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Podlevsky JD, Bley CJ, Omana RV, Qi X, Chen JJ (January 2008). «The telomerase database». Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (Database issue): D339–43. PMC 2238860

. PMID 18073191. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm700 Verifique data em:

. PMID 18073191. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm700 Verifique data em: |data=(ajuda) - ↑ Blevins T, Rajeswaran R, Shivaprasad PV, Beknazariants D, Si-Ammour A, Park HS, Vazquez F, Robertson D, Meins F, Hohn T, Pooggin MM (2006). «Four plant Dicers mediate viral small RNA biogenesis and DNA virus induced silencing». Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (21): 6233–46. PMC 1669714

. PMID 17090584. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl886

. PMID 17090584. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl886

- ↑ Jana S, Chakraborty C, Nandi S, Deb JK (November 2004). «RNA interference: potential therapeutic targets». Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 65 (6): 649–57. PMID 15372214. doi:10.1007/s00253-004-1732-1 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Schultz U, Kaspers B, Staeheli P (May 2004). «The interferon system of non-mammalian vertebrates». Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 28 (5): 499–508. PMID 15062646. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2003.09.009 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Whitehead KA, Dahlman JE, Langer RS, Anderson DG (2011). «Silencing or stimulation? siRNA delivery and the immune system». Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. 2: 77–96. PMID 22432611. doi:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114133

- ↑ Hsu, Ming-Ta; Coca-Prados, Miguel (26 July 1979). «Electron microscopic evidence for the circular form of RNA in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells». Nature (em inglês). 280 (5720): 339–340. ISSN 1476-4687. doi:10.1038/280339a0 Verifique data em:

|data=(ajuda) - ↑ Dahm R (fevereiro de 2005). «Friedrich Miescher and the discovery of DNA». Developmental Biology. 278 (2): 274–88. PMID 15680349. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.028

- ↑ Caspersson T, Schultz J (1939). «Pentose nucleotides in the cytoplasm of growing tissues». Nature. 143 (3623): 602–3. Bibcode:1939Natur.143..602C. doi:10.1038/143602c0

- ↑ Ochoa S (1959). «Enzymatic synthesis of ribonucleic acid» (PDF). Nobel Lecture. Consultado em 29 de abril de 2018

- ↑ Rich A, Davies D (1956). «A New Two-Stranded Helical Structure: Polyadenylic Acid and Polyuridylic Acid». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 78 (14): 3548–3549. doi:10.1021/ja01595a086

- ↑ Holley RW, et al. (março de 1965). «Structure of a ribonucleic acid». Science. 147 (3664): 1462–5. Bibcode:1965Sci...147.1462H. PMID 14263761. doi:10.1126/science.147.3664.1462

- ↑ «ABC (Madrid) - 15/02/1993, p. 70 - ABC.es Hemeroteca». hemeroteca.abc.es (em espanhol). Consultado em 29 de abril de 2018

- ↑ Magi, Lucia (20 de fevereiro de 2012). «Renato Dulbecco, el genetista que vinculó virus y cáncer». Madrid. El País (em espanhol). ISSN 1134-6582

- ↑ Fiers W, et al. (abril de 1976). «Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of the replicase gene». Nature. 260 (5551): 500–7. Bibcode:1976Natur.260..500F. PMID 1264203. doi:10.1038/260500a0

- ↑ País, Ediciones El (12 de outubro de 1993). «Dos biólogos obtienen el Nobel de Medicina por un descubrimiento en la estructura de los genes». Madrid. El País (em espanhol). ISSN 1134-6582

- ↑ Shampo, Marc A.; Kyle, Robert A.; Steensma, David P. (2010–2012). «Sidney Altman—Nobel Laureate for Work With RNA». Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 87 (10): e73. ISSN 0025-6196. PMC 3498233

. PMID 23036683. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.01.022. Consultado em 29 de abril de 2018

. PMID 23036683. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.01.022. Consultado em 29 de abril de 2018

- ↑ Napoli C, Lemieux C, Jorgensen R (abril de 1990). «Introduction of a Chimeric Chalcone Synthase Gene into Petunia Results in Reversible Co-Suppression of Homologous Genes in trans». The Plant Cell. 2 (4): 279–289. PMC 159885

. PMID 12354959. doi:10.1105/tpc.2.4.279

. PMID 12354959. doi:10.1105/tpc.2.4.279

- ↑ Dafny-Yelin M, Chung SM, Frankman EL, Tzfira T (dezembro de 2007). «pSAT RNA interference vectors: a modular series for multiple gene down-regulation in plants». Plant Physiology. 145 (4): 1272–81. PMC 2151715

. PMID 17766396. doi:10.1104/pp.107.106062

. PMID 17766396. doi:10.1104/pp.107.106062

- ↑ Ruvkun G (outubro de 2001). «Molecular biology. Glimpses of a tiny RNA world». Science. 294 (5543): 797–9. PMID 11679654. doi:10.1126/science.1066315

- ↑ Hopkin, Michael (2 de outubro de 2006). «RNAi scoops medical Nobel». news@nature (em inglês). ISSN 1744-7933. doi:10.1038/news061002-2

- ↑ Conger, Krista. «Roger Kornberg wins the 2006 Nobel Prize in Chemistry». Stanford University (em inglês). Consultado em 29 de abril de 2018

- ↑ Fichou Y, Férec C (dezembro de 2006). «The potential of oligonucleotides for therapeutic applications». Trends in Biotechnology. 24 (12): 563–70. PMID 17045686. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.003

- ↑ Siebert S (2006). «Common sequence structure properties and stable regions in RNA secondary structures» (PDF). Dissertation, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität, Freiburg im Breisgau. p. 1. Consultado em 29 de abril de 2018. Arquivado do original (PDF) em 9 de março de 2012

- ↑ Szathmáry E (junho de 1999). «The origin of the genetic code: amino acids as cofactors in an RNA world». Trends in Genetics. 15 (6): 223–9. PMID 10354582. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01730-8

- ↑ Marlaire R (3 de março de 2015). «NASA Ames Reproduces the Building Blocks of Life in Laboratory». NASA. Consultado em 29 de abril de 2018

External links[editar | editar código-fonte]

- RNA World website Link collection (structures, sequences, tools, journals)

- Nucleic Acid Database Images of DNA, RNA and complexes.

- Anna Marie Pyle's Seminar: RNA Structure, Function, and Recognition

Predefinição:Genetics Predefinição:Gene expression Predefinição:RNA-footer Predefinição:Nucleic acids Predefinição:Good article