Cronologia da evolução: diferenças entre revisões

| Linha 66: | Linha 66: | ||

|- valign="TOP" |

|- valign="TOP" |

||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4510 Ma |

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4510 Ma |

||

| De acordo com a [[hipótese do grande impacto]], a [[Lua]] se originou quando o planeta Terra e o planeta hipotético [[Theia]] colidiram, enviando um número grande muito de rocha lunar em órbita ao redor da Terra jovem, que eventualmente se fundiram para formar a Lua.<ref>{{Citar web|url= http://www.psi.edu/epo/moon/moon.html |título= The Origin of the Moon |último1 = Herres |primeiro1 = Gregg |último2 = Hartmann |primeiro2 = William K |authorlink2= William Kenneth Hartmann |website= Planetary Science Institute |local= Tucson, AZ |acessodata= 2015-03-04|data= 2010-09-07 }}</ref> A força gravitacional da nova Lua estabilizou o [[Rotação da Terra|eixo de rotação]] flutuante da Terra e estabeleceu as condições nas quais a [[abiogênese]] poderia ocorrer.<ref>{{citar periódico|autor = Astrobio |data= 24 de setembro de 2001 |título= Making the Moon |url= http://www.astrobio.net/topic/solar-system/meteoritescomets-and-asteroids/making-the-moon/ |periódico= Astrobiology Magazine |tipo= Based on a [[Southwest Research Institute]] press release |issn= 2152-1239 |acessodata= 2015-03-04 |citação= Because the Moon helps stabilize the tilt of the Earth's rotation, it prevents the Earth from wobbling between climatic extremes. Without the Moon, seasonal shifts would likely outpace even the most adaptable forms of life.}}</ref> |

| De acordo com a [[hipótese do grande impacto]], a [[Lua]] se originou quando o planeta Terra e o planeta hipotético [[Theia]] colidiram, enviando um número grande muito de rocha lunar em órbita ao redor da Terra jovem, que eventualmente se fundiram para formar a Lua.<ref>{{Citar web|url= http://www.psi.edu/epo/moon/moon.html |título= The Origin of the Moon |último1 = Herres |primeiro1 = Gregg |último2 = Hartmann |primeiro2 = William K |authorlink2= William Kenneth Hartmann |website= Planetary Science Institute |local= Tucson, AZ |acessodata= 2015-03-04|data= 2010-09-07 }}</ref> A força gravitacional da nova Lua [[Acoplamento de maré|estabilizou]] o [[Rotação da Terra|eixo de rotação]] flutuante da Terra e estabeleceu as condições nas quais a [[abiogênese]] poderia ocorrer.<ref>{{citar periódico|autor = Astrobio |data= 24 de setembro de 2001 |título= Making the Moon |url= http://www.astrobio.net/topic/solar-system/meteoritescomets-and-asteroids/making-the-moon/ |periódico= Astrobiology Magazine |tipo= Based on a [[Southwest Research Institute]] press release |issn= 2152-1239 |acessodata= 2015-03-04 |citação= Because the Moon helps stabilize the tilt of the Earth's rotation, it prevents the Earth from wobbling between climatic extremes. Without the Moon, seasonal shifts would likely outpace even the most adaptable forms of life.}}</ref> |

||

|- valign="TOP" |

|- valign="TOP" |

||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4404 Ma |

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4404 Ma |

||

| Linha 94: | Linha 94: | ||

|- valign="TOP" |

|- valign="TOP" |

||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4100 Ma |

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4100 Ma |

||

|Preservação mais precoce possível do carbono biogênico.<ref>{{ |

|Preservação mais precoce possível do carbono biogênico.<ref>{{Citar web |data=2015-10-19 |título=4.1-billion-year-old crystal may hold earliest signs of life |url=https://www.sciencenews.org/article/41-billion-year-old-crystal-may-hold-earliest-signs-life |acessodata=2023-08-08 |língua=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Citar jornal |último1=Bell |primeiro1=Elizabeth A. |último2=Boehnke |primeiro2=Patrick |último3=Harrison |primeiro3=T. Mark |último4=Mao |primeiro4=Wendy L. |data=2015-11-24 |título=Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon |jornal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |language=en |volume=112 |edição=47 |páginas=14518–14521 |doi=10.1073/pnas.1517557112 |issn=0027-8424 |pmc=4664351 |pmid=26483481 |bibcode=2015PNAS..11214518B |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

||

|- valign="TOP" |

|- valign="TOP" |

||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4100–3800 Ma |

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4100–3800 Ma |

||

|[[Intenso bombardeio tardio|Intenso Bombardeio Tardio]] (IBT): barragem estendida de meteoroides [[Evento de impacto|impactando]] os planetas telúricos.<ref>{{ |

|[[Intenso bombardeio tardio|Intenso Bombardeio Tardio]] (IBT): barragem estendida de meteoroides [[Evento de impacto|impactando]] os planetas telúricos.<ref>{{citar jornal |último1= Abramov |primeiro1= Oleg |último2=Mojzsis |primeiro2=Stephen J. |data=21 de maio de 2009 |título=Microbial habitability of the Hadean Earth during the late heavy bombardment |url=http://isotope.colorado.edu/2009_Abramov_Mojzsis_Nature.pdf |jornal=[[Nature]] |volume=459 |edição=7245 |páginas=419–422 |bibcode=2009Natur.459..419A |doi=10.1038/nature08015 |issn=0028-0836 |pmid=19458721 |s2cid=3304147 |acessodata=2015-03-04 }}</ref> O fluxo térmico da atividade hidrotérmica generalizada durante o IBT pode ter ajudado na abiogênese e na diversificação inicial da vida. Possíveis restos de [[Material biótico|vida biótica]] foram encontrados em rochas de 4,1 bilhões de anos na [[Austrália Ocidental]].<ref name="AP-20151019">{{citar notícia |último= Borenstein |primeiro=Seth |título=Hints of life on what was thought to be desolate early Earth |url= http://apnews.excite.com/article/20151019/us-sci--earliest_life-a400435d0d.html |data= 19 de outubro de 2015 |obra= [[Excite]] |local= Yonkers, NY |publicado= [[Mindspark Interactive Network]] |agência=[[Associated Press]] |acessodata=2015-10-20}}</ref><ref name="PNAS-20151014-pdf">{{citar jornal |último1= Bell |primeiro1= Elizabeth A. |último2= Boehnike |primeiro2=Patrick |último3=Harrison |primeiro3=T. Mark |último4=Mao |primeiro4=Wendy L. |numero-autores=3 |data= 24 de novembro de 2015 |título= Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon |url= http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2015/10/14/1517557112.full.pdf |jornal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume= 112 |edição= 47 |páginas= 14518–14521 |doi=10.1073/pnas.1517557112 |issn=0027-8424 |acessodata= 2015-12-30 |pmid=26483481 |pmc=4664351|bibcode=2015PNAS..11214518B |doi-access=free }}</ref> Provável origem da vida. |

||

|- valign="TOP" |

|- valign="TOP" |

||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4000 Ma |

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4000 Ma |

||

|Formação do [[cinturão de rochas verdes]] na gnaisse Acasta no cratón Slave em [[Territórios do Noroeste]], no Canadá, um cinturão de rocha mais velho no mundo.<ref name="Bjornerud">{{harvnb|Bjornerud|2005}}</ref> |

|Formação do [[cinturão de rochas verdes]] na [[gnaisse Acasta]] no [[cratón Slave]] em [[Territórios do Noroeste]], no Canadá, um cinturão de rocha mais velho no mundo.<ref name="Bjornerud">{{harvnb|Bjornerud|2005}}</ref> |

||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 3900–2500 Ma |

|||

| Aparecem [[célula]]s semelhantes a [[procarionte]]s.<ref>{{citar jornal |último1= Woese |primeiro1= Carl |autorlink1=Carl Woese |último2=Gogarten |primeiro2=J. Peter |autorlink2=Johann Peter Gogarten |data= 21 de outubro de 1999 |título= When did eukaryotic cells (cells with nuclei and other internal organelles) first evolve? What do we know about how they evolved from earlier life-forms? |url= http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/when-did-eukaryotic-cells/ |jornal=[[Scientific American]] |issn= 0036-8733 |acessodata=2015-03-04}}</ref> Esses primeiros organismos são acreditados{{Por quem|data=Novembro de 2021}} teriam sido [[Quimiotrófico|quimioautotróficos]], usando [[dióxido de carbono]] como fonte de [[carbono]] e [[Oxirredução|oxidando]] materiais inorgânicos para extrair energia. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 3800 Ma |

|||

| Formação de um cinturão de rochas verdes do complexo de [[Cinturão de Rochas Verdes Isua|Isua]] no oeste da [[Groenlândia]], cujas frequências isotópicas sugerem a presença de vida.<ref name="Bjornerud" /> As primeiras evidências de vida na Terra incluem: [[hematita]] [[Substância biogênica|biogênica]] de 3,8 bilhões de anos em uma [[Formações ferríferas bandadas|formação ferrífera em faixas]] do [[Cinturão de Rochas Verdes Nuvvuagittuq]], no Canadá;<ref>{{citar notícia|autor= Nicole Mortilanno|url= http://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/oldest-record-life-earth-found-quebec-1.4004545|título=Oldest traces of life on Earth found in Quebec, dating back roughly 3.8 billion years |obra=CBC News}}</ref> [[grafite]] em [[Rocha metassedimentar|rochas metassedimentares]] de 3,7 bilhões de anos no oeste da Groenlândia;<ref name="NG-20131208">{{citar jornal |último1=Ohtomo |primeiro1=Yoko |último2=Kakegawa |primeiro2=Takeshi |último3=Ishida |primeiro3=Akizumi |último4= Nagase |primeiro4=Toshiro |último5=Rosing |primeiro5=Minik T. |data=Janeiro de 2014 |título=Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks |jornal= [[Nature Geoscience]] |volume= 7 |edição= 1 |página=25–28 |doi=10.1038/ngeo2025 |issn=1752-0894 |numero-autores=3 |bibcode=2014NatGe...7...25O}}</ref> e [[Fóssil|fósseis]] de [[tapete microbiano]] em [[arenito]] de 3,48 bilhões de anos na [[Austrália Ocidental]].<ref name="AP-20131113">{{citar notícia |último= Borenstein |primeiro= Seth |data= 13 de novembro de 2013 |título=Oldest fossil found: Meet your microbial mom |url= http://apnews.excite.com/article/20131113/DAA1VSC01.html |obra=Excite |local=Yonkers, NY |publicado= Mindspark Interactive Network |agência= Associated Press |acessodata= 2013-11-15}}</ref><ref name="AST-20131108">{{citar jornal |último1=Noffke |primeiro1=Nora |autorlink1=Nora Noffke |último2=Christian |primeiro2=Daniel |último3=Wacey |primeiro3= David |último4=Hazen |primeiro4=Robert M. |autorlink4=Robert Hazen |data=8 de novembro de 2013 |título= Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures Recording an Ancient Ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 Billion-Year-Old Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia |jornal= [[Astrobiology (periódico)|Astrobiology]] |volume= 13 |edição=12 |páginas=1103–1124 |doi=10.1089/ast.2013.1030 |issn=1531-1074 |pmc=3870916 |pmid= 24205812 |bibcode=2013AsBio..13.1103N }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 3800–3500 Ma |

|||

| [[Último ancestral comum universal]] (LUCA):<ref>{{citar jornal |último= Doolittle |primeiro= W. Ford |autorlink= Ford Doolittle |data=Fevereiro de 2000 |título=Uprooting the Tree of Life |url= http://shiva.msu.montana.edu/courses/mb437_537_2004_fall/docs/uprooting.pdf |jornal=[[Scientific American]] |volume=282 |edição=2 |páginas=90–95 |doi=10.1038/scientificamerican0200-90 |issn=0036-8733 |pmid= 10710791 |arquivourl= https://web.archive.org/web/20060907081933/http://shiva.msu.montana.edu/courses/mb437_537_2004_fall/docs/uprooting.pdf |arquivodata= 2006-09-07 |acessodata= 2015-04-05 |bibcode= 2000SciAm.282b..90D }}</ref><ref>{{citar jornal |último1= Glansdorff |primeiro1= Nicolas |autor2= Ying Xu |último3= Labedan |primeiro3= Bernard |data= 9 de julho de 2008 |título= The Last Universal Common Ancestor: emergence, constitution and genetic legacy of an elusive forerunner |jornal= [[Biology Direct]] |volume= 3 |página= 29 |doi= 10.1186/1745-6150-3-29 |issn=1745-6150 |pmc=2478661 |pmid=18613974 |doi-access= free }}</ref> dividido entre [[bactéria]]s e [[Archaea|arqueias]].<ref>{{citar jornal |último1=Hahn |primeiro1=Jürgen |último2=Haug |primeiro2= Pat |data=Maio de 1986 |título=Traces of Archaebacteria in ancient sediments |jornal=Systematic and Applied Microbiology |volume=7 |edição=2–3 |páginas=178–183 |doi=10.1016/S0723-2020(86)80002-9 |issn=0723-2020 }}</ref> |

|||

As bactérias desenvolvem a [[fotossíntese]] primitiva, que a princípio não produzia [[Oxigénio|oxigênio]].<ref>{{citar jornal |último= Olson |primeiro= John M. |data= Maio de 2006 |título= Photosynthesis in the Archean era |jornal= Photosynthesis Research |volume= 88 |issue= 2 |páginas= 109–117 |doi= 10.1007/s11120-006-9040-5 |issn= 0166-8595 |pmid=16453059 |bibcode= 2006PhoRe..88..109O |s2cid=20364747 }}</ref> Esses organismos exploram um [[Gradiente eletroquímico|gradiente de prótons]] para gerar [[trifosfato de adenosina]] (ATP), um mecanismo usado por praticamente todos os organismos subsequentes.<ref>{{citar web|url= http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/why-are-cells-powered-by-proton-gradients-14373960|título=Proton Gradient, Cell Origin, ATP Synthase - Learn Science at Scitable|website= www.nature.com}}</ref><ref>{{citar jornal |último1= Romano |primeiro1= Antonio H. |último2= Conway |primeiro2= Tyrrell |data= Julho–Setembro de 1996 |título= Evolution of carbohydrate metabolic pathways |jornal= Research in Microbiology |volume= 147 |edição=6–7 |páginas=448–455 |doi=10.1016/0923-2508(96)83998-2 |issn=0923-2508 |pmid=9084754 }}</ref><ref>{{citar jornal |último=Knowles |primeiro=Jeremy R. |autorlink=Jeremy R. Knowles |data=Julho de 1980 |título= Enzyme-Catalyzed Phosphoryl Transfer Reactions |jornal=[[Annual Review of Biochemistry]] |volume=49 |páginas= 877–919 |doi=10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.004305 |issn=0066-4154 |pmid=6250450 }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 3000 Ma |

|||

| Fotossintetizam [[Cyanobacteria|cianobactérias]] usando água como [[Redução|agente redutor]] e produzindo oxigênio como resíduo.<ref name="Buick, R. 2008">{{citar jornal |último= Buick |primeiro= Roger |data= 27 de agosto de 2008 |título= When did oxygenic photosynthesis evolve? |jornal= [[Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B]] |volume= 363 |edição= 1504 |páginas=2731–2743 |doi=10.1098/rstb.2008.0041 |issn= 0962-8436 |pmc=2606769 |pmid=18468984 }}</ref> O oxigênio livre inicialmente óxido de ferro dissolvido nos oceanos, criando [[minério de ferro]]. A concentração de oxigênio na atmosfera aumenta lentamente, [[Veneno|envenenando]] muitas bactérias e eventualmente desencadeando o [[Grande Evento de Oxigenação]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 2800 Ma |

|||

| Evidências mais antigas de vida microbiana em terra na forma de [[paleossolo]]s ricos em matéria orgânica, [[Lagoa efêmera|lagoas efêmeras]] e sequências [[Aluvião|aluviais]], algumas contendo [[Micropaleontologia|microfósseis]].<ref name="Beraldi-Campesi">{{citar jornal |último=Beraldi-Campesi |primeiro=Hugo |data= 23 de fevereiro de 2013 |título=Early life on land and the first terrestrial ecosystems |url= http://www.ecologicalprocesses.com/content/pdf/2192-1709-2-1.pdf |jornal= Ecological Processes |volume= 2 |edição=1 |páginas=4 |doi=10.1186/2192-1709-2-1 |s2cid=44199693 |issn=2192-1709 |doi-access= free |bibcode=2013EcoPr...2....1B }}</ref> |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

<!--- |

|||

=== Proterozoic Eon === |

|||

[[File:Endomembrane system diagram en (edit).svg|thumb|right|240px|Detail of the [[eukaryote]] [[endomembrane system]] and its components]] |

|||

[[File:Ceratium furca.jpg|thumb|right|240px|Dinoflagellate ''[[Ceratium furca]]'']] |

|||

[[File:Mikrofoto.de-Blepharisma japonicum 15.jpg|thumb|right|240px|''[[Blepharisma japonicum]]'', a free-living [[ciliate]]d [[protozoa]]n]] |

|||

[[File:DickinsoniaCostata.jpg|thumb|right|240px|''[[Dickinsonia|Dickinsonia costata]]'', an iconic [[Ediacaran biota|Ediacaran organism]], displays the characteristic quilted appearance of Ediacaran enigmata.]] |

|||

{{Main|Proterozoic}} |

|||

2500 Ma – 539 Ma. Contains the [[Palaeoproterozoic]], [[Mesoproterozoic]] and [[Neoproterozoic]] eras. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Date |

|||

! Event |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 2500 Ma |

|||

|[[Great Oxidation Event]] led by cyanobacteria's oxygenic photosynthesis.<ref name="Buick, R. 2008" /> Commencement of [[plate tectonics]] with old marine crust dense enough to [[subduction|subduct]].<ref name="Bjornerud" /> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap |2023 Ma |

|||

|Formation of the [[Vredefort impact structure]], one of the largest and oldest verified impact structures on Earth. The crater is estimated to have been between {{convert|170-300|km|mi}} across when it first formed.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Huber |first1=M. S. |last2=Kovaleva |first2=E. |last3=Rae |first3=A. S. P |last4=Tisato |first4=N. |last5=Gulick |first5=S. P. S |date=August 2023 |title=Can Archean Impact Structures Be Discovered? A Case Study From Earth's Largest, Most Deeply Eroded Impact Structure |journal=Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets |volume=128 |issue=8 |doi=10.1029/2022JE007721 |issn=2169-9097 |doi-access=free|bibcode=2023JGRE..12807721H }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | By 1850 Ma |

|||

| [[Eukaryote|Eukaryotic]] cells, containing membrane-bound [[organelle]]s with diverse functions, probably derived from prokaryotes engulfing each other via [[phagocytosis]]. (See [[Symbiogenesis]] and [[Endosymbiont]]). Bacterial viruses ([[bacteriophage]]s) emerge before or soon after the divergence of the prokaryotic and eukaryotic lineages.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bernstein |first1=Harris |last2=Bernstein |first2=Carol |date=May 1989 |title=Bacteriophage T4 genetic homologies with bacteria and eucaryotes |journal=[[Journal of Bacteriology]] |volume=171 |issue=5 |pages=2265–2270 |issn=0021-9193 |pmc=209897 |pmid=2651395 |doi=10.1128/jb.171.5.2265-2270.1989 }}</ref> [[Red beds]] show an oxidising atmosphere, favouring the spread of eukaryotic life.<ref>{{harvnb|Bjornerud|2005|p=151}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Knoll |first1=Andrew H. |last2=Javaux |first2=Emmanuelle J. |last3=Hewitt |first3=David |last4=Cohen |first4=Phoebe |display-authors=3 |date=June 29, 2006 |title=Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans |journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B |volume=361 |issue=1470 |pages=1023–1038 |doi=10.1098/rstb.2006.1843 |issn=0962-8436 |pmc=1578724 |pmid=16754612}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Fedonkin |first=Mikhail A. |author-link=Mikhail Fedonkin |date=March 31, 2003 |title=The origin of the Metazoa in the light of the Proterozoic fossil record |journal=Paleontological Research |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=9–41 |doi=10.2517/prpsj.7.9 |s2cid=55178329 |issn=1342-8144 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 1500 Ma |

|||

|[[Volyn biota]], a collection of exceptionally well-preserved [[microfossil]]s with varying morphologies.<ref name=fra2022>{{cite journal |author=Franz G., Lyckberg P., Khomenko V., Chournousenko V., Schulz H.-M., Mahlstedt N., Wirth R., Glodny J., Gernert U., Nissen J. |title=Fossilization of Precambrian microfossils in the Volyn pegmatite, Ukraine |journal=Biogeosciences |volume=19 |issue=6 |date=2022 |pages=1795–1811 |doi=10.5194/bg-19-1795-2022 |bibcode=2022BGeo...19.1795F |url=https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/19/1795/2022/bg-19-1795-2022.pdf |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 1300 Ma |

|||

| Earliest land [[Fungus|fungi]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://science.psu.edu/news-and-events/2001-news/Hedges8-2001.htm |title=First Land Plants and Fungi Changed Earth's Climate, Paving the Way for Explosive Evolution of Land Animals, New Gene Study Suggests |work=science.psu.edu |access-date=10 April 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180408205932/http://science.psu.edu/news-and-events/2001-news/Hedges8-2001.htm |archive-date=2018-04-08 |url-status=dead |quote=The researchers found that land plants had evolved on Earth by about 700 million years ago and land fungi by about 1,300 million years ago — much earlier than previous estimates of around 480 million years ago, which were based on the earliest fossils of those organisms.}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | By 1200 Ma |

|||

| [[Meiosis]] and [[Sex|sexual reproduction]] in single-celled eukaryotes, possibly even in the common ancestor of all eukaryotes<ref>{{harvnb|Bernstein|Bernstein|Michod|2012|pp=1–50}}</ref> or in the [[RNA world hypothesis|RNA world]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bernstein |first1=Harris |last2=Byerly |first2=Henry C. |last3=Hopf |first3=Frederic A. |last4=Michod |first4=Richard E. |date=October 7, 1984 |title=Origin of sex |journal=[[Journal of Theoretical Biology]] |volume=110 |issue=3 |pages=323–351 |doi=10.1016/S0022-5193(84)80178-2 |issn=0022-5193 |pmid=6209512 |bibcode=1984JThBi.110..323B }}</ref> [[Evolution of sexual reproduction|Sexual reproduction]] may have increased the rate of evolution.<ref name="dateref">{{cite journal |last=Butterfield |first=Nicholas J. |date=Summer 2000 |title=''Bangiomorpha pubescens'' n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes |url=http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/content/26/3/386.abstract |journal=[[Paleobiology (journal)|Paleobiology]] |volume=26 |issue=3 |pages=386–404 |doi=10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2 |s2cid=36648568 |issn=0094-8373 }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align='RIGHT' nowrap | By 1000 Ma |

|||

| First non-marine eukaryotes move onto land. They were photosynthetic and multicellular, indicating that plants evolved much earlier than originally thought.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Earth's earliest non-marine eukaryotes |journal=Nature |volume=473 |issue=7348 |pages=505–509 |doi=10.1038/nature09943 |pmid=21490597 |date=26 May 2011|bibcode=2011Natur.473..505S |last1=Strother |first1=Paul K. |last2=Battison |first2=Leila |last3=Brasier |first3=Martin D. |last4=Wellman |first4=Charles H. |s2cid=4418860 }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP' |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 750 Ma |

|||

| Beginning of [[Animal#Evolutionary origin|animal evolution]].<ref name="NYT-20191127">{{cite news |last=Zimmer |first=Carl |author-link=Carl Zimmer |title=Is This the First Fossil of an Embryo? - Mysterious 609-million-year-old balls of cells may be the oldest animal embryos — or something else entirely. |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/27/science/fossil-embryo-paleontology-caveaspharea.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220101/https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/27/science/fossil-embryo-paleontology-caveaspharea.html |archive-date=2022-01-01 |url-access=limited |date=27 November 2019 |work=[[The New York Times]] |access-date=28 November 2019 }}{{cbignore}}</ref><ref name="BE-20161205">{{cite journal |author=Cunningham, John A. |display-authors=et al. |title=The origin of animals: Can molecular clocks and the fossil record be reconciled? |date=5 December 2016 |journal=[[BioEssays]] |volume=39 |issue=1 |pages=e201600120 |doi=10.1002/bies.201600120 |pmid=27918074 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 720–630 Ma |

|||

| Possible [[Snowball Earth|global glaciation]]<ref name="Hoffman1998">{{cite journal |last1=Hoffman |first1=Paul F. |author-link1=Paul F. Hoffman |last2=Kaufman |first2=Alan J. |last3=Halverson |first3=Galen P. |last4=Schrag |first4=Daniel P. |author-link4=Daniel P. Schrag |date=August 28, 1998 |title=A Neoproterozoic Snowball Earth |url=http://www.snowballearth.org/pdf/Hoffman_Science1998.pdf |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |volume=281 |issue=5381 |pages=1342–1346 |bibcode=1998Sci...281.1342H |doi=10.1126/science.281.5381.1342 |issn=0036-8075 |pmid=9721097 |s2cid=13046760 |access-date=2007-05-04 }}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Kirschvink|1992|pp=51–52}}</ref> which increased the atmospheric [[oxygen]] and decreased [[carbon dioxide]], and was either ''caused'' by land plant evolution<ref>{{cite web |title=First Land Plants and Fungi Changed Earth's Climate, Paving the Way for Explosive Evolution of Land Animals, New Gene Study Suggests |url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2001/08/010810070021.htm |access-date=25 May 2022 |work=www.sciencedaily.com}}</ref> or ''resulted'' in it.<ref name="Zarsky-et-al-2022">{{cite journal | last1=Žárský | first1=J. | last2=Žárský | first2=V. | last3=Hanáček | first3=M. | last4=Žárský | first4=V. | title=Cryogenian Glacial Habitats as a Plant Terrestrialisation Cradle – The Origin of the Anydrophytes and Zygnematophyceae Split | journal=[[Frontiers in Plant Science]] | publisher=[[Frontiers Media|Frontiers]] | volume=12 | date=2022-01-27 | page=735020 | issn=1664-462X | doi=10.3389/fpls.2021.735020| pmid=35154170 | pmc=8829067 | doi-access=free }}</ref> Opinion is divided on whether it increased or decreased biodiversity or the rate of evolution.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Boyle |first1=Richard A. |last2=Lenton |first2=Timothy M. |author-link2=Tim Lenton |last3=Williams |first3=Hywel T. P. |date=December 2007 |title=Neoproterozoic 'snowball Earth' glaciations and the evolution of altruism |url=http://researchpages.net/media/resources/2007/06/21/richtimhywelfinal.pdf |journal=[[Geobiology (journal)|Geobiology]] |volume=5 |issue=4 |pages=337–349 |doi=10.1111/j.1472-4669.2007.00115.x |bibcode=2007Gbio....5..337B |s2cid=14827354 |issn=1472-4677 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080910213718/http://researchpages.net/media/resources/2007/06/21/richtimhywelfinal.pdf |archive-date=2008-09-10 |access-date=2015-03-09 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Corsetti |first1=Frank A. |last2=Awramik |first2=Stanley M. |author-link2=Stanley Awramik |last3=Pierce |first3=David |date=April 15, 2003 |title=A complex microbiota from snowball Earth times: Microfossils from the Neoproterozoic Kingston Peak Formation, Death Valley, USA |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=100 |issue=8 |pages=4399–4404 |bibcode=2003PNAS..100.4399C |doi=10.1073/pnas.0730560100 |issn=0027-8424 |pmc=153566 |pmid=12682298 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="Corsetti2006">{{cite journal |last1=Corsetti |first1=Frank A. |last2=Olcott |first2=Alison N. |last3=Bakermans |first3=Corien |date=March 22, 2006 |title=The biotic response to Neoproterozoic snowball Earth |journal=[[Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology]] |volume=232 |issue=2–4 |pages=114–130 |doi=10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.10.030 |issn=0031-0182 |bibcode=2006PPP...232..114C }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 600 Ma |

|||

| Accumulation of atmospheric oxygen allows the formation of an [[ozone layer]].<ref name="Formation of the Ozone Layer">{{cite web |url=http://disc.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/ozone/additional/science-focus/about-ozone/ozone_formation.shtml |title=Formation of the Ozone Layer |date=September 9, 2009 |work=Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center |publisher=NASA |access-date=2013-05-26}}</ref> Previous land-based life would probably have required other chemicals to attenuate [[ultraviolet]] radiation.<ref name="Beraldi-Campesi" /> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="Right" nowrap | 580–542 Ma |

|||

| [[Ediacaran biota]], the first large, complex aquatic multicellular organisms.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://geol.queensu.ca/people/narbonne/recent_pubs1.html |title=The Origin and Early Evolution of Animals |last=Narbonne |first=Guy |date=January 2008 |publisher=[[Queen's University at Kingston|Queen's University]] |location=Kingston, Ontario, Canada |access-date=2007-03-10 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150724081804/http://geol.queensu.ca/people/narbonne/recent_pubs1.html |archive-date=2015-07-24 }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 580–500 Ma |

|||

| [[Cambrian explosion]]: most modern animal [[phylum|phyla]] appear.<ref name="BerkeleyCambrian">{{cite web |url=http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cambrian/cambrian.php |title=The Cambrian Period |last1=Waggoner |first1=Ben M. |last2=Collins |first2=Allen G. |last3=Hsu |first3=Karen |last4=Kang |first4=Myun |last5=Lavarias |first5=Amy |last6=Prabaker |first6=Kavitha |last7=Skaggs |first7=Cody |date=November 22, 1994 |editor1-last=Rieboldt |editor1-first=Sarah |editor2-last=Smith |editor2-first=Dave |website=Tour of geologic time |publisher=[[University of California Museum of Paleontology]] |location=Berkeley, CA |type=Online exhibit |display-authors=2 |access-date=2015-03-09}}</ref><ref name="BristolUCEtiming">{{cite web |url=http://palaeo.gly.bris.ac.uk/Palaeofiles/Cambrian/timing/timing.html |title=Timing |last=Lane |first=Abby |date=January 20, 1999 |website=The Cambrian Explosion |publisher=[[University of Bristol]] |location=Bristol, England |access-date=2015-03-09}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 550–540 Ma |

|||

| [[Ctenophora]] (comb jellies),<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Chen |first1=Jun-Yuan |last2=Schopf |first2=J. William |last3=Bottjer |first3=David J. |last4=Zhang |first4=Chen-Yu |last5=Kudryavtsev |first5=Anatoliy B. |last6=Tripathi |first6=Abhishek B. |last7=Wang |first7=Xiu-Qiang |last8=Yang |first8=Yong-Hua |last9=Gao |first9=Xiang |last10=Yang |first10=Ying |date=2007-04-10 |title=Raman spectra of a Lower Cambrian ctenophore embryo from southwestern Shaanxi, China |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=104 |issue=15 |pages=6289–6292 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0701246104 |issn=0027-8424 |pmc=1847456 |pmid=17404242|bibcode=2007PNAS..104.6289C |doi-access=free }}</ref> [[Sponge|Porifera]] (sponges),<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Müller |first1=W. E. G. |last2=Jinhe Li |last3=Schröder |first3=H. C. |last4=Li Qiao |last5=Xiaohong Wang |date=2007-05-03 |title=The unique skeleton of siliceous sponges (Porifera; Hexactinellida and Demospongiae) that evolved first from the Urmetazoa during the Proterozoic: a review |url=https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/4/219/2007/ |journal=Biogeosciences |language=English |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=219–232 |doi=10.5194/bg-4-219-2007 |bibcode=2007BGeo....4..219M |s2cid=15471191 |issn=1726-4170|doi-access=free }}</ref> [[Anthozoa]] ([[coral]]s and [[sea anemone]]s),<ref>{{Cite web |date=2018-12-11 |title=Corals and sea anemones (anthozoa) |url=https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/corals-and-sea-anemones-anthozoa |access-date=2022-09-24 |website=Smithsonian's National Zoo |language=en}}</ref> ''[[Ikaria wariootia]]'' (an early [[Bilateria]]n).<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Grazhdankin |first=Dima |date=February 8, 2016 |title=Patterns of distribution in the Ediacaran biotas: facies versus biogeography and evolution |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/paleobiology/article/abs/patterns-of-distribution-in-the-ediacaran-biotas-facies-versus-biogeography-and-evolution/E1A8C6052128EB081CB260731B5628A6 |journal=Paleobiology |language=en |volume=30 |issue=2 |pages=203–221 |doi=10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0203:PODITE>2.0.CO;2 |s2cid=129376371 |issn=0094-8373}}</ref> |

|||

|} |

|||

=== Phanerozoic Eon === |

|||

{{Main|Phanerozoic}} |

|||

539 Ma – present |

|||

The [[Phanerozoic]] Eon (Greek: period of well-displayed life) marks the appearance in the fossil record of abundant, shell-forming and/or trace-making organisms. It is subdivided into three eras, the [[Paleozoic]], [[Mesozoic]] and [[Cenozoic]], with major [[mass extinction]]s at division points. |

|||

==== Palaeozoic Era ==== |

|||

{{Main|Paleozoic}} |

|||

{{More citations needed|section|date=September 2022}} |

|||

538.8 Ma – 251.9 Ma and contains the [[Cambrian]], [[Ordovician]], [[Silurian]], [[Devonian]], [[Carboniferous]] and [[Permian]] periods. |

|||

[[File:Nautilus profile.jpg|240px|thumb|With only a handful of species surviving today, the [[Nautiloid]]s flourished during the early [[Paleozoic era]], from the [[Late Cambrian]], where they constituted the main predatory animals.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lindgren |first1=A.R. |last2=Giribet |first2=G. |last3=Nishiguchi |first3=M.K. |title=A combined approach to the phylogeny of Cephalopoda (Mollusca) |journal=Cladistics |date=2004 |volume=20 |issue=5 |pages=454–486 |url=http://faculty.uml.edu/rhochberg/hochberglab/Courses/InvertZool/Cephalopod%20phylogeny.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150210223626/http://faculty.uml.edu/rhochberg/hochberglab/Courses/InvertZool/Cephalopod%20phylogeny.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=2015-02-10 |doi=10.1111/j.1096-0031.2004.00032.x |pmid=34892953 |citeseerx=10.1.1.693.2026 |s2cid=85975284 }}</ref>]] |

|||

[[File:Haikouichthys 3d.png|240px|thumb|''[[Haikouichthys]]'', a [[jawless fish]], is popularized as one of the [[evolution of fish|earliest fishes]] and probably a basal [[chordate]] or a basal [[craniate]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.palaeos.com/Paleozoic/Cambrian/Cambrian.2.html |title=Palaeos Paleozoic: Cambrian: The Cambrian Period - 2 |access-date=2009-04-20 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090429021119/http://www.palaeos.com/Paleozoic/Cambrian/Cambrian.2.html |archive-date=2009-04-29 }}</ref> ]] |

|||

[[File:Sa-fern.jpg|240px|thumb|[[Ferns]] first appear in the fossil record about 360 million years ago in the late [[Devonian]] period.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/plants/pterophyta/pteridofr.html |title=Pteridopsida: Fossil Record |publisher=University of California Museum of Paleontology | access-date=2014-03-11 }}</ref>]] |

|||

[[File:Dimetrodon grandis 3D Model Reconstruction.png|thumb|240px|[[Synapsid]]s such as ''[[Dimetrodon]]'' were the largest [[Tetrapod|terrestrial vertebrates]] in the [[Permian]] period, 299 to 251 million years ago.]] |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Date |

|||

! Event |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 535 Ma |

|||

| [[Cambrian explosion|Major diversification]] of living things in the oceans: [[arthropod]]s (e.g. trilobites, [[crustacean]]s), [[chordates]], [[echinoderm]]s, [[Mollusca|mollusc]]s, [[brachiopod]]s, [[Foraminifera|foraminifers]] and [[radiolaria]]ns, etc. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 530 Ma |

|||

| The first known footprints on land date to 530 Ma.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Clarke |first=Tom |date=April 30, 2002 |title=Oldest fossil footprints on land |url=http://www.nature.com/news/2002/020430/full/news020429-2.html |journal=Nature |doi=10.1038/news020429-2 |issn=1744-7933 |access-date=2015-03-09 |quote=The oldest fossils of footprints ever found on land hint that animals may have beaten plants out of the primordial seas. Lobster-sized, centipede-like animals made the prints wading out of the ocean and scuttling over sand dunes about 530 million years ago. Previous fossils indicated that animals didn't take this step until 40 million years later.}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 520 Ma |

|||

| Earliest [[Graptolithina|graptolites]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Graptolites |url=https://www.bgs.ac.uk/discovering-geology/fossils-and-geological-time/graptolites/ |access-date=2022-09-24 |website=British Geological Survey |language=en-GB}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 511 Ma |

|||

|Earliest [[crustacean]]s.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Leutwyler |first=Kristin |title=511-Million-Year-Old Fossil Suggests Pre-Cambrian Origins for Crustaceans |url=https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/511-million-year-old-foss/ |access-date=2022-09-24 |website=Scientific American |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 505 Ma |

|||

| [[Fossil#Fossilization processes|Fossilization]] of the [[Burgess Shale]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 500 Ma |

|||

|[[Jellyfish]] have existed since at least this time. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 485 Ma |

|||

| First vertebrates with true bones ([[Agnatha|jawless fishes]]). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 450 Ma |

|||

| First complete [[conodont]]s and [[Sea urchin|echinoid]]s appear. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 440 Ma |

|||

| First agnathan fishes: [[Heterostraci]], [[Galeaspida]], and [[Pituriaspida]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 420 Ma |

|||

| Earliest [[Actinopterygii|ray-finned fishes]], [[Trigonotarbida|trigonotarbid arachnids]], and land [[scorpion]]s.<ref name="Garwood">{{cite journal |last1=Garwood |first1=Russell J. |last2=Edgecombe |first2=Gregory D. |date=September 2011 |title=Early Terrestrial Animals, Evolution, and Uncertainty |journal=Evolution: Education and Outreach |volume=4 |issue=3 |pages=489–501 |doi=10.1007/s12052-011-0357-y |issn=1936-6426 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 410 Ma |

|||

| First signs of teeth in fish. Earliest [[Nautilida]], [[Lycopodiophyta|lycophytes]], and [[Trimerophytopsida|trimerophytes]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap="" | 488–400 Ma |

|||

| First [[cephalopod]]s ([[nautiloid]]s)<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Landing |first1=Ed |last2=Westrop |first2=Stephen R. |title=Lower Ordovician Faunas, Stratigraphy, and Sea-Level History of the Middle Beekmantown Group, Northeastern New York |date=September 1, 2006 |url=https://bioone.org/journals/journal-of-paleontology/volume-80/issue-5/0022-3360_2006_80_958_LOFSAS_2.0.CO_2/LOWER-ORDOVICIAN-FAUNAS-STRATIGRAPHY-AND-SEA-LEVEL-HISTORY-OF-THE/10.1666/0022-3360(2006)80[958:LOFSAS]2.0.CO;2.full |journal=Journal of Paleontology |volume=80 |issue=5 |pages=958–980 |doi=10.1666/0022-3360(2006)80[958:LOFSAS]2.0.CO;2 |s2cid=130848432 |issn=0022-3360}}</ref> and [[chiton]]s.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Serb |first1=Jeanne M. |last2=Eernisse |first2=Douglas J. |date=September 25, 2008 |title=Charting Evolution's Trajectory: Using Molluscan Eye Diversity to Understand Parallel and Convergent Evolution |journal=Evolution: Education and Outreach |language=en |volume=1 |issue=4 |pages=439–447 |doi=10.1007/s12052-008-0084-1 |s2cid=2881223 |issn=1936-6434|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 395 Ma |

|||

| First [[lichen]]s, [[Charales|stoneworts]]. Earliest [[Opiliones|harvestmen]], [[mite]]s, [[Hexapoda|hexapod]]s ([[springtail]]s) and [[Ammonoidea|ammonoid]]s. The earliest known tracks on land named the [[Zachelmie trackways]] which are possibly related to [[Ichthyostegalia|icthyostegalians]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Niedźwiedzki |first1=Grzegorz |last2=Szrek |first2=Piotr |last3=Narkiewicz |first3=Katarzyna |last4=Narkiewicz |first4=Marek |last5=Ahlberg |first5=Per E. |date=January 1, 2010 |title=Tetrapod trackways from the early Middle Devonian period of Poland |url=https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/46752909/trackways-with-cover-page-v2.pdf?Expires=1664076708&Signature=T90exV-98rO1WUlSoLdNXTzzvqxsI-rCpzhxd1xC6Pt2wc-hH2xVdXEP57MFHFhPw5yfMK9kf5bRJ6WTM1WH-jXOTPfHoKUJVPH-s50O0~h6F0yg1HemExF546SgHoUEJ4a-HVpyzB2IXHNB8atvNjpfHTburCWCtaN8h4-Axs8yadT5uS8rNSgBgOZeXYJdHYk9D3FZ3vuEUC44QTxZKio2qF7G32CvptPzkd7D8IPzcqIUymSeErAXy9zTp1Ep2Vc9ttecV4DqNuV0VSGewUek-JvvBfI4gwaRJxOdZCvpoyDVRGfE5~xNYcGvmZr1WsAnHTOMRNmYDxGklQ52fw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA |journal=Nature |language=en |volume=463 |issue=7277 |pages=43–48 |doi=10.1038/nature08623 |pmid=20054388 |bibcode=2010Natur.463...43N |s2cid=4428903 |issn=1476-4687}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 375 Ma |

|||

|[[Tiktaalik]], a lobe-finned fish with some anatomical features similar to early tetrapods. It has been suggested to be a transitional species between fish and tetrapods.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Details of Evolutionary Transition from Fish to Land Animals Revealed |url=https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=112416 |access-date=2022-09-25 |website=www.nsf.gov |language=English}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 365 Ma |

|||

|''[[Acanthostega]]'' is one of the earliest vertebrates capable of walking.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Clack |first=Jennifer A. |date=November 21, 2005 |title=Getting a Leg Up on Land |url=http://sciam.com/print_version.cfm?articleID=000DC8B8-EA15-137C-AA1583414B7F0000 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070225023805/http://sciam.com/print_version.cfm?articleID=000DC8B8-EA15-137C-AA1583414B7F0000 |archive-date=2007-02-25 |journal=Scientific American|volume=293 |issue=6 |pages=100–107 |doi=10.1038/scientificamerican1205-100 |pmid=16323697 |bibcode=2005SciAm.293f.100C }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 363 Ma |

|||

| By the start of the [[Carboniferous]] Period, the Earth begins to resemble its present state. Insects roamed the land and would soon take to the skies; [[shark]]s swam the oceans as top predators,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.elasmo-research.org/education/evolution/evol_s_predator.htm |title=Evolution of a Super Predator |last=Martin |first=R. Aidan |website=Biology of Sharks and Rays |publisher=ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research |location=North Vancouver, BC, Canada |access-date=2015-03-10 |quote=The ancestry of sharks dates back more than 200 million years before the earliest known dinosaur.}}</ref> and vegetation covered the land, with [[Spermatophyte|seed-bearing plants]] and [[forest]]s soon to flourish. |

|||

Four-limbed tetrapods gradually gain adaptations which will help them occupy a terrestrial life-habit. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 360 Ma |

|||

| First [[crab]]s and [[Pteridophyte|ferns]]. Land flora dominated by [[Pteridospermatophyta|seed ferns]]. The Xinhang forest grows around this time.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.sci-news.com/paleontology/xinhang-forest-07484.html|title=Devonian Fossil Forest Unearthed in China {{!}} Paleontology {{!}} Sci-News.com|website=Breaking Science News {{!}} Sci-News.com|language=en-US|access-date=2019-09-28}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 350 Ma |

|||

| First large sharks, [[Chimaeridae|ratfishes]], and [[hagfish]]; first crown [[tetrapods]] (with five digits and no fins and scales). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 350 Ma |

|||

| Diversification of [[amphibian]]s.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Amphibia |url=https://paleobiodb.org/classic/checkTaxonInfo?taxon_no=36319&is_real_user=1 |access-date=2022-10-07 |website=paleobiodb.org}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 325-335 Ma |

|||

| First [[Reptiliomorpha]].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Benton|first1=M.J.|last2=Donoghue|first2=P.C.J.|year=2006|title=Palaeontological evidence to date the tree of life|journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution|volume=24|issue=1|pages=26–53|doi=10.1093/molbev/msl150|pmid=17047029|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 330-320 Ma |

|||

| First [[amniote]] vertebrates (''[[Paleothyris]]'').<ref>{{Cite web |title=Origin and Early Evolution of Amniotes {{!}} Frontiers Research Topic |url=https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/14947/origin-and-early-evolution-of-amniotes#:~:text=Amniotes%20first%20appeared%20in%20the%20fossil%20record%20about%20318%20million,attention%20over%20the%20past%20decades. |access-date=2022-10-07 |website=www.frontiersin.org}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 320 Ma |

|||

| [[Synapsid]]s (precursors to mammals) separate from [[Sauropsida|sauropsid]]s (reptiles) in late Carboniferous.<ref name="Amniota">{{cite web |url=http://www.palaeos.org/Amniota |title=Amniota |website=[[Palaeos]] |access-date=2015-03-09}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 305 Ma |

|||

| The [[Carboniferous rainforest collapse]] occurs, causing a minor extinction event, as well as paving the way for amniotes to become dominant over amphibians and seed plants over ferns and lycophytes. |

|||

First [[diapsid]] reptiles (e.g. ''[[Petrolacosaurus]]''). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 280 Ma |

|||

| Earliest [[beetle]]s, seed plants and [[Pinophyta|conifer]]s diversify while [[Lepidodendrales|lepidodendrid]]s and [[Equisetopsida|sphenopsid]]s decrease. [[Landform|Terrestrial]] temnospondyl amphibians and pelycosaurs (e.g. ''[[Dimetrodon]]'') diversify in species. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 275 Ma |

|||

| [[Therapsid]] synapsids separate from pelycosaur synapsids. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 265 Ma |

|||

|[[Gorgonopsia]]ns appear in the fossil record.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kemp |first=T. S. |date=February 16, 2006 |title=The origin and early radiation of the therapsid mammal-like reptiles: a palaeobiological hypothesis |journal=Journal of Evolutionary Biology |language=en |volume=19 |issue=4 |pages=1231–1247 |doi=10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.01076.x |pmid=16780524 |s2cid=3184629 |issn=1010-061X|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 251.9–251.4 Ma |

|||

| The [[Permian–Triassic extinction event]] eliminates over 90-95% of marine species. Terrestrial organisms were not as seriously affected as the marine biota. This "clearing of the slate" may have led to an ensuing diversification, but life on land took 30 million years to completely recover.<ref name="SahneyBenton2008RecoveryFromProfoundExtinction">{{cite journal |last1=Sahney |first1=Sarda |last2=Benton |first2=Michael J. |author-link2=Michael Benton |date=April 7, 2008 |title=Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time |journal=[[Proceedings of the Royal Society B]] |volume=275 |issue=1636 |pages=759–765 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2007.1370 |issn=0962-8452 |pmc=2596898 |pmid=18198148 }}</ref> |

|||

|} |

|||

==== Mesozoic Era ==== |

|||

{{Main|Mesozoic}} |

|||

{{More citations needed|section|date=September 2022}} |

|||

[[File:Utatsusaurus BW.jpg|thumb|right|240px|''[[Utatsusaurus]]'' is the earliest-known [[ichthyopterygia]]n.]] |

|||

[[File:Plateosaurus panorama.jpg|thumb|right|240px|''[[Plateosaurus engelhardti]]'']] |

|||

[[File:Cycas circinalis.jpg|thumb|right|240px|''[[Cycas circinalis]]'']] |

|||

[[File:Tyrannosaurus Rex Jane.jpg|thumb|240px|For about 150 million years, [[dinosaur]]s were the dominant land animals on Earth.]] |

|||

From 251.9 Ma to 66 Ma and containing the [[Triassic]], [[Jurassic]] and [[Cretaceous]] periods. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Date |

|||

! Event |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap |250 Ma |

|||

| [[Mesozoic marine revolution]] begins: increasingly well adapted and diverse predators stress [[sessility (zoology)|sessile]] marine groups; the "balance of power" in the oceans shifts dramatically as some groups of prey adapt more rapidly and effectively than others. |

|||

|- |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 250 Ma |

|||

|''[[Triadobatrachus massinoti]]'' is the earliest known frog. |

|||

|- |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 248 Ma |

|||

|[[Sturgeon]] and [[paddlefish]] ([[Acipenseridae]]) first appear. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 245 Ma |

|||

| Earliest [[Ichthyopterygia|ichthyosaurs]] |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 240 Ma |

|||

| Increase in diversity of [[Eucynodontia|cynodont]]s and [[rhynchosaur]]s |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 225 Ma |

|||

| Earliest dinosaurs ([[Plateosauridae|prosauropod]]s), first [[Cockle (bivalve)|cardiid]] [[Bivalvia|bivalve]]s, diversity in [[cycad]]s, [[Bennettitales|bennettitaleans]], and conifers. First [[Teleostei|teleost]] fishes. First mammals (''[[Adelobasileus]]''). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 220 Ma |

|||

| Seed-producing [[Gymnosperm]] forests dominate the land; herbivores grow to huge sizes to accommodate the large guts necessary to digest the nutrient-poor plants.{{Citation needed|date=August 2007}} First [[Fly|flies]] and [[turtle]]s (''[[Odontochelys]]''). First [[Coelophysoidea|coelophysoid]] dinosaurs. First [[mammals]] from small-sized [[cynodont]]s, which transitioned towards a nocturnal, insectivorous, and endothermic lifestyle. |

|||

|- |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap |205 Ma |

|||

|[[Triassic–Jurassic extinction event|Massive Triassic/Jurassic extinction]]. It wipes out all [[pseudosuchia]]ns except [[crocodylomorphs]], who transitioned to an aquatic habitat, while [[dinosaurs]] took over the land and [[pterosaurs]] filled the air. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| style="text-align:RIGHT;" nowrap=""| 200 Ma |

|||

| First accepted evidence for [[virus]]es infecting eukaryotic cells (the group [[Geminiviridae]]).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mcb.uct.ac.za/tutorial/virorig.html |title=Origins of Viruses |last=Rybicki |first=Ed |date=April 2008 |website=Introduction of Molecular Virology |publisher=[[University of Cape Town]] |location=Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa |type=Lecture |access-date=2015-03-10 |quote=Viruses of nearly all the major classes of organisms - animals, plants, fungi and bacteria / archaea - probably evolved with their hosts in the seas, given that most of the evolution of life on this planet has occurred there. This means that viruses also probably emerged from the waters with their different hosts, during the successive waves of colonisation of the terrestrial environment. |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090509094459/http://www.mcb.uct.ac.za/tutorial/virorig.html |archive-date=2009-05-09 }}</ref> However, viruses are still poorly understood and may have arisen before "life" itself, or may be a more recent phenomenon. |

|||

Major extinctions in terrestrial vertebrates and large amphibians. Earliest examples of [[Thyreophora|armoured dinosaurs]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 195 Ma |

|||

| First pterosaurs with specialized feeding (''[[Dorygnathus]]''). First [[Sauropoda|sauropod]] dinosaurs. Diversification in small, [[ornithischia]]n dinosaurs: [[Heterodontosauridae|heterodontosaurid]]s, [[Fabrosauridae|fabrosaurid]]s, and [[Scelidosaurus|scelidosaurids]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 190 Ma |

|||

| [[Pliosauroidea|Pliosauroid]]s appear in the fossil record. First [[Lepidoptera|lepidopteran insects]] (''[[Archaeolepis]]''), [[hermit crab]]s, modern [[starfish]], irregular echinoids, [[Corbulidae|corbulid]] bivalves, and [[Bryozoa|tubulipore bryozoan]]s. Extensive development of [[sponge reef]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 176 Ma |

|||

| First [[Stegosauria]]n dinosaurs. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 170 Ma |

|||

| Earliest [[salamander]]s, [[newt]]s, [[Cryptoclididae|cryptoclidid]]s, [[Elasmosauridae|elasmosaurid]] [[Plesiosauria|plesiosaur]]s, and [[cladotheria]]n mammals. Sauropod dinosaurs diversify. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 168 Ma |

|||

| First [[lizard]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 165 Ma |

|||

| First [[Batoidea|rays]] and [[Glycymerididae|glycymeridid]] bivalves. First [[vampire squid]]s.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/vampire-squid-fish.html|title=What are the vampire squid and the vampire fish?|last=US Department of Commerce|first=National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration|website=oceanservice.noaa.gov|language=EN-US|access-date=2019-09-27}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 163 Ma |

|||

| [[Pterodactyloidea|Pterodactyloid]] pterosaurs first appear.<ref>{{cite news |last=Dell'Amore |first=Christine |date=April 24, 2014 |title=Meet Kryptodrakon: Oldest Known Pterodactyl Found in China |url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/04/140424-pterodactyl-pterosaur-china-oldest-science-animals/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140425022505/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/04/140424-pterodactyl-pterosaur-china-oldest-science-animals/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=April 25, 2014 |work=National Geographic News |location=Washington, D.C. |publisher=National Geographic Society |access-date=2014-04-25}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 161 Ma |

|||

| [[Ceratopsia]]n dinosaurs appear in the fossil record (''[[Yinlong]]'') and the oldest known eutherian mammal: ''[[Juramaia]]''. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 160 Ma |

|||

| [[Multituberculata|Multituberculate]] mammals (genus ''[[Rugosodon]]'') appear in eastern [[China]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 155 Ma |

|||

| First blood-sucking insects ([[Ceratopogonidae|ceratopogonid]]s), [[Rudists|rudist]] bivalves, and [[Cheilostomata|cheilostome]] bryozoans. ''[[Archaeopteryx]]'', a possible ancestor to the birds, appears in the fossil record, along with [[Triconodontidae|triconodontid]] and [[Symmetrodonta|symmetrodont]] mammals. Diversity in [[stegosauria]]n and [[theropod]] dinosaurs. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 131 Ma |

|||

|First [[Pine|pine trees]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 140 Ma |

|||

|[[Orb-weaver spider|Orb-weaver]] spiders appear. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 135 Ma |

|||

| Rise of the [[Flowering plant|angiosperm]]s. Some of these flowering plants bear structures that attract insects and other animals to spread [[pollen]]; other angiosperms are pollinated by wind or water. This innovation causes a major burst of animal [[coevolution]]. First freshwater [[Pelomedusidae|pelomedusid]] turtles. Earliest [[krill]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 120 Ma |

|||

| Oldest fossils of [[heterokont]]s, including both marine [[diatom]]s and [[Dictyochales|silicoflagellate]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 115 Ma |

|||

| First [[monotreme]] mammals. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 114 Ma |

|||

| Earliest [[bee]]s.<ref name="bees-argentina">{{cite web |last=Greshko |first=Michael |title=Oldest evidence of modern bees found in Argentina |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/oldest-ever-fossil-bee-nests-discovered-in-patagonia |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210223204426/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/oldest-ever-fossil-bee-nests-discovered-in-patagonia |url-status=dead |archive-date=February 23, 2021 |website=National Geographic |access-date=2022-06-22 |quote=The model shows that modern bees started diversifying at a breakneck pace about 114 million years ago, right around the time that eudicots—the plant group that comprises 75 percent of flowering plants—started branching out. The results, which confirm some earlier genetic studies, strengthen the case that flowering plants and pollinating bees have coevolved from the very beginning. |date=2020-02-11}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 112 Ma |

|||

|''[[Xiphactinus]]'', a large predatory fish, appears in the fossil record. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 110 Ma |

|||

| First [[hesperornithes]], toothed diving birds. Earliest [[Limopsidae|limopsid]], [[Verticordiidae|verticordiid]], and [[Thyasiridae|thyasirid]] bivalves. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap="" | 100 Ma |

|||

| First [[ant]]s.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Moreau |first1=Corrie S. |last2=Bell |first2=Charles D. |last3=Vila |first3=Roger |last4=Archibald |first4=S. Bruce |last5=Pierce |first5=Naomi E. |date=2006-04-07 |title=Phylogeny of the Ants: Diversification in the Age of Angiosperms |url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1124891 |journal=Science |language=en |volume=312 |issue=5770 |pages=101–104 |doi=10.1126/science.1124891 |pmid=16601190 |bibcode=2006Sci...312..101M |s2cid=20729380 |issn=0036-8075}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap="" | 100–95 Ma |

|||

| ''[[Spinosaurus]]'', the largest theropod dinosaur, appears in the fossil record.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2020-09-23 |title=Case for 'river monster' Spinosaurus strengthened by new fossil teeth |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/case-for-river-monster-spinosaurus-strengthened-by-new-fossil-teeth |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210613184807/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/case-for-river-monster-spinosaurus-strengthened-by-new-fossil-teeth |url-status=dead |archive-date=June 13, 2021 |access-date=2022-10-03 |website=Science |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap="" | 95 Ma |

|||

|First [[crocodilia]]ns evolve.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Mindat.org |url=https://www.mindat.org/taxon-704.html |access-date=2022-10-03 |website=www.mindat.org}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 90 Ma |

|||

| Extinction of ichthyosaurs. Earliest [[snake]]s and [[Nuculanidae|nuculanid]] bivalves. Large diversification in angiosperms: [[magnoliids]], [[rosids]], [[Hamamelidaceae|hamamelidids]], [[Monocotyledon|monocots]], and [[ginger]]. Earliest examples of [[tick]]s. Probable origins of [[Placentalia|placental]] mammals (earliest undisputed fossil evidence is 66 Ma). |

|||

|- |

|||

|86–76 Ma |

|||

|Diversification of therian mammals.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Grossnickle |first1=David M. |last2=Newham |first2=Elis |date=2016-06-15 |title=Therian mammals experience an ecomorphological radiation during the Late Cretaceous and selective extinction at the K–Pg boundary |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences |volume=283 |issue=1832 |pages=20160256 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2016.0256 |pmc=4920311}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Mammals began their takeover long before the death of the dinosaurs |url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/06/160607220628.htm |access-date=2022-09-25 |website=ScienceDaily |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 70 Ma |

|||

| Multituberculate mammals increase in diversity. First [[Yoldiidae|yoldiid]] bivalves. First possible [[ungulates]] (''Protungulatum''). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 68–66 Ma |

|||

| ''[[Tyrannosaurus]]'', the largest terrestrial predator of western [[Laramidia|North America]], appears in the fossil record. First species of ''[[Triceratops]].''<ref>{{Cite web |last=Finds |first=Study |date=2021-12-02 |title=T-rex fossil reveals dinosaur from 68 million years ago likely had a terrible toothache! |url=https://studyfinds.org/t-rex-fossil-toothache/ |access-date=2022-09-24 |website=Study Finds |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

|} |

|||

==== Cenozoic Era ==== |

|||

{{Main|Cenozoic}} |

|||

{{More citations needed|section|date=September 2022}} |

|||

66 Ma – present |

|||

[[File:Patriofelis-mount.jpg|thumb|right|240px|Mount of oxyaenid ''[[Patriofelis]]'' from the [[American Museum of Natural History]] ]] |

|||

[[File:Icaronycteris index.jpg|thumb|right|240px|The bat ''[[Icaronycteris]]'' appeared 52.2 million years ago]] |

|||

[[File:Grassflowers.jpg|thumb|right|240px|Grass flowers]] |

|||

[[File:1064376 - Megafauna - Museu Nacional de História Natural UFRJ - 22 Outubro 2010 - Rio de Janeiro - Brazil.jpg|thumb|240px|Reconstructed skeletons of [[flightless bird|flightless]] [[Paraphysornis|terror bird]] and [[ground sloth]] at the Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro]] |

|||

[[File:Diprotodon optatum (2).jpg|thumb|240px|''[[Diprotodon]]'' went extinct about 40,000 years ago as part of the [[Quaternary extinction event]], along with every other Australian creature over {{cvt|100|kg}}.]] |

|||

[[File:Homo floresiensis v 2-0.jpg|thumb|240px|50,000 years ago several different [[Human evolution|human species]] coexisted on Earth including modern humans and ''[[Homo floresiensis]]'' (pictured).]] |

|||

[[File:PantheraLeoAtrox1 (retouched).jpg|thumb|240px|[[American lion]]s exceeded extant [[lion]]s in size and ranged over much of North America until 11,000 BP.]] |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Date |

|||

! Event |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 66 Ma |

|||

|The [[Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event]] eradicates about half of all animal species, including [[mosasaur]]s, pterosaurs, plesiosaurs, [[ammonite]]s, [[Belemnitida|belemnites]], rudist and [[Inoceramidae|inoceramid]] bivalves, most planktic foraminifers, and all of the dinosaurs excluding the birds.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Chiappe |first1=Luis M. |author-link1=Luis M. Chiappe |last2=Dyke |first2=Gareth J. |author-link2=Gareth J. Dyke |date=November 2002 |title=The Mesozoic Radiation of Birds |journal=[[Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics|Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics]] |volume=33 |pages=91–124 |doi=10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150517 |issn=1545-2069 }}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 66 Ma- |

|||

| Rapid dominance of conifers and [[ginkgos]] in high latitudes, along with mammals becoming the dominant species. First [[Psammobiidae|psammobiid]] bivalves. Earliest [[rodent]]s. Rapid diversification in ants. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 63 Ma |

|||

| Evolution of the [[Creodonta|creodont]]s, an important group of meat-eating ([[Carnivore|carnivorous]]) mammals. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 62 Ma |

|||

|Evolution of the first [[penguin]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 60 Ma |

|||

| Diversification of large, [[flightless bird]]s. Earliest true [[primate]]s,{{Who|date=January 2019}} along with the first [[Semelidae|semelid]] bivalves, [[Xenarthra|edentate]], [[carnivora]]n and [[Insectivora|lipotyphlan]] mammals, and [[owl]]s. The ancestors of the carnivorous mammals ([[miacids]]) were alive.{{Citation needed|date=January 2019}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 59 Ma |

|||

|Earliest [[sailfish]] appear. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 56 Ma |

|||

| ''[[Gastornis]]'', a large flightless bird, appears in the fossil record. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 55 Ma |

|||

| Modern bird groups diversify (first [[Passerine|song birds]], [[parrot]]s, [[loon]]s, [[Swift (bird)|swift]]s, [[woodpecker]]s), first [[Archaeoceti|whale]] (''[[Himalayacetus]]''), earliest [[lagomorph]]s, [[armadillo]]s, appearance of [[sirenia]]n, [[proboscidea]]n mammals in the fossil record. Flowering plants continue to diversify. The ancestor (according to theory) of the species in the genus ''[[Carcharodon]]'', the early [[Isurus|mako shark]] ''Isurus hastalis'', is alive. Ungulates split into [[artiodactyla]] and [[perissodactyla]], with [[Cetacea|some members]] of the former returning to the sea. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 52 Ma |

|||

| First [[bat]]s appear (''[[Onychonycteris]]''). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 50 Ma |

|||

| Peak diversity of dinoflagellates and [[Coccolithophore|nannofossil]]s, increase in diversity of [[Pholadomyoida|anomalodesmatan]] and heteroconch bivalves, [[Brontotheriidae|brontothere]]s, [[tapir]]s, [[rhinoceros]]es, and [[camel]]s appear in the fossil record, diversification of primates. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 40 Ma |

|||

| Modern-type [[butterflies]] and [[moths]] appear. Extinction of ''[[Gastornis]]''. ''[[Basilosaurus]]'', one of the first of the giant whales, appeared in the fossil record. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 38 Ma |

|||

|Earliest [[bear]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 37 Ma |

|||

| First [[Nimravidae|nimravid]] ("false saber-toothed cats") carnivores — these species are unrelated to modern-type [[Felidae|feline]]s. First [[alligator]]s and [[ruminants]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 35 Ma |

|||

| [[Poaceae|Grasses]] diversify from among the monocot [[angiosperm]]s; [[grassland]]s begin to expand. Slight increase in diversity of cold-tolerant [[ostracod]]s and foraminifers, along with major extinctions of [[Gastropoda|gastropod]]s, reptiles, amphibians, and multituberculate mammals. Many modern mammal groups begin to appear: first [[Glyptodontidae|glyptodonts]], [[ground sloth]]s, [[canid]]s, [[Peccary|peccaries]], and the first [[eagle]]s and [[hawk]]s. Diversity in [[Toothed whale|toothed]] and [[Baleen whale|baleen]] whales. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 33 Ma |

|||

| Evolution of the [[Thylacinidae|thylacinid]] [[marsupial]]s (''[[Badjcinus]]''). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 30 Ma |

|||

| First [[barnacle|balanids]] and [[eucalypt]]s, extinction of [[Embrithopoda|embrithopod]] and brontothere mammals, earliest [[Suidae|pig]]s and [[Felidae|cat]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 28 Ma |

|||

| ''[[Paraceratherium]]'' appears in the fossil record, the largest terrestrial mammal that ever lived. First [[pelican]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 25 Ma |

|||

| ''[[Pelagornis sandersi]]'' appears in the fossil record, the largest flying bird that ever lived. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 25 Ma |

|||

| First [[deer]]. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 24 Ma |

|||

|First [[pinniped]]s. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 23 Ma |

|||

|Earliest [[Struthio|ostriches]], trees representative of most major groups of [[oak]]s have appeared by now.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.oaksofchevithornebarton.com/about-history-of-garden.cfm?|title=About > The Origins of Oaks|website=www.oaksofchevithornebarton.com|access-date=2019-09-28}}</ref> |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 20 Ma |

|||

| First [[giraffe]]s, [[hyena]]s, and [[giant anteater]]s, increase in bird diversity. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 17 Ma |

|||

|First birds of the genus [[Corvus]] (crows). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 15 Ma |

|||

| Genus ''[[Mammut]]'' appears in the fossil record, first [[Bovidae|bovid]]s and [[kangaroo]]s, diversity in [[Australian megafauna]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 10 Ma |

|||

| Grasslands and [[savanna]]s are established, diversity in insects, especially ants and [[termite]]s, [[horse]]s increase in body size and develop [[Hypsodont|high-crowned teeth]], major diversification in grassland mammals and snakes. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap="" | 9.5 Ma {{Dubious |Great American Interchange|reason=Date is too early; it should be more like 2.7 mya|date=March 2020}} |

|||

|[[Great American Interchange]], where various land and freshwater faunas migrated between North and [[South America]]. Armadillos, [[opossum]]s, [[hummingbird]]s [[Phorusrhacidae|Phorusrhacids]], [[Ground sloth|Ground Sloths]], [[Glyptodont]]s, and [[Meridiungulata|Meridiungulates]] traveled to North America, while [[horse]]s, [[tapir]]s, [[saber-toothed cat]]s, [[jaguar]]s, [[bear]]s, [[coati]]es, [[ferret]]s, [[otter]]s, [[skunk]]s and deer entered South America. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 9 Ma |

|||

|First [[platypus]]es. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 6.5 Ma |

|||

| First [[Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor|hominin]]s (''[[Sahelanthropus]]''). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 6 Ma |

|||

| [[Australopithecine]]s diversify (''[[Orrorin]]'', ''[[Ardipithecus]]''). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 5 Ma |

|||

| First [[sloth|tree sloths]] and [[Hippopotamus|hippopotami]], diversification of grazing herbivores like [[zebra]]s and [[elephant]]s, large carnivorous mammals like [[lion]]s and the genus ''[[Canis]]'', burrowing rodents, kangaroos, birds, and small carnivores, [[vulture]]s increase in size, decrease in the number of perissodactyl mammals. Extinction of nimravid carnivores. First [[leopard seal]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4.8 Ma |

|||

| [[Mammoth]]s appear in the fossil record. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4.5 Ma |

|||

|[[Marine iguana]]s diverge from land iguanas. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 4 Ma |

|||

| ''[[Australopithecus]]'' evolves. ''[[Stupendemys]]'' appears in the fossil record as the largest freshwater turtle, first modern elephants, giraffes, zebras, lions, rhinoceros and [[gazelle]]s appear in the fossil record |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 3.6 Ma |

|||

|[[Blue whale]]s grow to modern size. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 3 Ma |

|||

|Earliest [[swordfish]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 2.7 Ma |

|||

| ''[[Paranthropus]] evolves.'' |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 2.5 Ma |

|||

| Earliest species of ''[[Arctodus]]'' and ''[[Smilodon]]'' evolve. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 2 Ma |

|||

| First members of genus ''Homo'', [[Homo habilis|Homo Habilis]], appear in the fossil record. Diversification of conifers in high latitudes. The eventual ancestor of cattle, [[aurochs]] (''Bos primigenus''), evolves in India. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 1.7 Ma |

|||

| Australopithecines go extinct. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 1.2 Ma |

|||

| Evolution of ''[[Homo antecessor]]''. The last members of ''Paranthropus'' die out. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 1 Ma |

|||

|First [[coyote]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 600 ka |

|||

| Evolution of ''[[Homo heidelbergensis]].'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 400 ka |

|||

|First [[polar bear]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 350 ka |

|||

| Evolution of [[Neanderthal]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 300 ka |

|||

| ''[[Gigantopithecus]]'', a giant relative of the [[orangutan]] from [[Asia]] dies out. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 250 ka |

|||

| Anatomically modern humans appear in [[Africa]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Karmin |first1=Monika |last2=Saag |first2=Lauri |last3=Vicente |first3=Mário |date=April 2015 |title=A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture |journal=[[Genome Research]] |volume=25 |issue=4 |pages=459–466 |doi=10.1101/gr.186684.114 |issn=1088-9051 |name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=etal |pmid=25770088 |pmc=4381518}}</ref><ref>{{cite press release |last1=Brown |first1=Frank |last2=Fleagle |first2=John |author-link2=John G. Fleagle |last3=McDougall |first3=Ian |author-link3=Ian McDougall (geologist) |date=February 16, 2005 |title=The Oldest Homo sapiens |url=http://unews.utah.edu/news_releases/the-oldest-homo-sapiens/ |location=Salt Lake City, UT |publisher=[[University of Utah]] |access-date=2015-03-10}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Alemseged |first1=Zeresenay |author-link1=Zeresenay Alemseged |last2=Coppens |first2=Yves |author-link2=Yves Coppens |last3=Geraads |first3=Denis |date=February 2002 |title=Hominid cranium from Homo: Description and taxonomy of Homo-323-1976-896 |journal=[[American Journal of Physical Anthropology]] |volume=117 |issue=2 |pages=103–112 |doi=10.1002/ajpa.10032 |issn=0002-9483 |pmid=11815945 |url=http://doc.rero.ch/record/13324/files/PAL_E59.pdf }}</ref> Around 50 ka they start colonising the other continents, replacing Neanderthals in [[Europe]] and other hominins in Asia. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 70 ka |

|||

| Genetic bottleneck in humans ([[Toba catastrophe theory]]). |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 40 ka |

|||

| Last giant monitor lizards ([[Megalania|Varanus priscus]]) die out. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 35-25 ka |

|||

| Extinction of [[Neanderthal]]s. Domestication of [[dog]]s. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 15 ka |

|||

| Last [[woolly rhinoceros]] (''Coelodonta antiquitatis'') are believed to have gone extinct. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 11 ka |

|||

| Short-faced bears vanish from North America, with the last [[Megatheriidae|giant ground sloths]] dying out. All [[Equidae]] become extinct in North America. Domestication of various [[ungulates]]. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap | 10 ka |

|||

| [[Holocene]] [[Epoch (geology)|epoch]] starts<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2014-10.jpg |title=International Stratigraphic Chart (v 2014/10) |publisher=[[International Commission on Stratigraphy]] |location=Beijing, China |format=PDF |access-date=2015-03-11}}</ref> after the [[Last Glacial Maximum]]. Last mainland species of [[woolly mammoth]] (''Mammuthus primigenus'') die out, as does the last ''Smilodon'' species. |

|||

|- valign="TOP" |

|||

| align="RIGHT" nowrap |8 ka |

|||

| The [[Subfossil lemur|Giant Lemur]] dies out. |

|||

|}---> |

|||

{{Desatualizada}} |

{{Desatualizada}} |

||

Edição atual tal como às 02h35min de 27 de janeiro de 2024

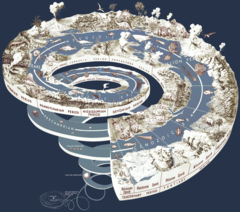

Esta Cronologia da evolução da vida delineia os maiores eventos no desenvolvimento da vida no planeta Terra. As datas dadas neste artigo baseiam-se em evidências científicas. Em biologia, evolução é o processo pelo qual populações de organismos adquirem e transmitem características novas de geração para geração. Os processos evolutivos influenciam a diversidade em todos os níveis da organização biológica, dos reinos as espécies. A sua ocorrência ao longo de longos períodos de tempo explica a origem de novas espécies e a vasta diversidade do mundo biológico. Espécies contemporâneas são relacionadas umas às outras por origem comum, produto da evolução e especiação ao longo de mil milhões de anos. As semelhanças entre todos os organismos atuais indicam a presença de um antepassado comum, do que houve evolução de todas as espécies conhecidas, vivas e extintas. Calcula-se que houve extinções de 99% de todas as espécies,[1][2] mas que somam mais de cinco mil milhões.[3]

As estimativas do número de espécies atuais na Terra variam de 10 a 14 milhões,[4] das quais aproximadamente 1,2 milhão foram documentadas e mais de 86% ainda não foram descritas.[5] No entanto, um relatório científico em maio de 2016, estima que 1 trilhão de espécies esteja atualmente na Terra, com apenas 0,001% descrito.[6]

Embora os dados apresentados neste artigo sejam estimativas baseadas em evidências científicas, houve controvérsia entre visões mais tradicionais de aumento da biodiversidade ao longo do tempo e a visão de que o modelo básico na Terra tem sido de aniquilação e diversificação e que em alguns tempos passados como a explosão cambriana, havia uma grande diversidade.[7][8]

Extinções[editar | editar código-fonte]

As espécies se extinguem constantemente à medida que os ambientes mudam, os organismos competem por lugares ambientais e a mutação genética leva ao surgimento de novas espécies em relação às mais antigas. Ocasionalmente, a biodiversidade na Terra é atingida na forma de uma extinção em massa, na qual a taxa de extinção é muito maior do que o normal. Um grande evento de extinção em massa geralmente representa um aumento de eventos menores de extinção que ocorrem em um período relativamente curto de tempo.