Usuário:Lucas Brandão/Testes

Esta é uma página de testes do utilizador Lucas Brandão, uma subpágina da principal. Serve como um local de testes e espaço de desenvolvimento, desta feita não é um artigo enciclopédico. Para uma página de testes sua, crie uma aqui. Como editar: Tutorial • Guia de edição • Livro de estilo • Referência rápida Como criar uma página: Guia passo a passo • Como criar • Verificabilidade • Critérios de notoriedade |

Esta página cita fontes, mas que não cobrem todo o conteúdo. |

| Johann Wolfgang von Goethe | |

|---|---|

| Goethe em 1828, pintura de Joseph Karl Stieler. | |

| Nascimento | 28 de agosto de 1749 Frankfurt am Main |

| Morte | 22 de março de 1832 (82 anos) Weimar |

| Nacionalidade | Alemão |

| Ocupação | Poeta, romancista, dramaturgo, diretor de teatro (Prinzipal), filósofo, teórico de arte, diplomata, funcionário do governo |

| Magnum opus | Fausto, Os Sofrimentos do Jovem Werther, "Os Anos de Aprendizado de Wilhelm Meister" |

| Assinatura | |

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (Frankfurt am Main, 28 de Agosto de 1749 — Weimar, 22 de Março de 1832) foi um autor e estadista alemão que também fez incursões pelo campo da ciência natural. Como escritor, Goethe foi uma das mais importantes figuras da literatura alemã[1] e do Romantismo europeu, nos finais do século XVIII e inícios do século XIX. Juntamente com Friedrich Schiller, foi um dos líderes do movimento literário romântico alemão Sturm und Drang.

De sua vasta produção fazem parte: romances, peças de teatro, poemas, escritos autobiográficos, reflexões teóricas nas áreas de arte, literatura e ciências naturais. Além disso, sua correspondência epistolar com pensadores e personalidades da época é grande fonte de pesquisa e análise de seu pensamento.

Através do romance Os Sofrimentos do Jovem Werther, Goethe tornou-se famoso em toda a Europa no ano de 1774 e, mais tarde, houve um amadurecimento de sua produção, influenciada sobretudo pela parceria com Schiller, no qual em conjunto tornou-se o mais importante autor do Classicismo de Weimar. Sua obra prima, porém, é o drama trágico Fausto, publicado em fragmento em 1790, depois em primeira parte definitiva em 1808 e, por fim, numa segunda parte, em 1832, ano de sua morte, tomando-lhe, portanto, a vida inteira. Goethe é até hoje considerado o mais importante escritor alemão, cuja obra influenciou a literatura de todo o mundo.[1]

Vida[editar | editar código-fonte]

Origem[editar | editar código-fonte]

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe nasceu em 28 de agosto de 1749 em Frankfurt am Main, Alemanha. Era o filho mais velho de Johann Caspar Goethe (Frankfurt am Main, 29 de Julho de 1710 - Frankfurt am Main, 25 de Maio de 1782). Homem culto, jurista que não exerceu a profissão, Caspar vivia dos rendimentos de sua fortuna. A mãe de Goethe, Catharina Elisabeth Textor Goethe (Frankfurt am Main, 19 de Fevereiro de 1731 – Frankfurt am Main, 15 de Setembro de 1808), casada em Frankfurt am Main a 20 de Agosto de 1748, procedia de uma família de poder econômico e posição social, sendo tetraneta duma irmã de Lucas Cranach, o Jovem, filho de Lucas Cranach, o Velho e descendente por bastardia do Landgrave Henrique III de Hesse-Marburg[2]. Casou-se aos 17 anos e teve outros filhos, dos quais apenas um viera a chegar à idade adulta.

Educados, inicialmente, pelo próprio pai e, depois, por tutores contratados, Goethe e a irmã receberam uma ampla educação que incluía o estudo de francês, inglês, italiano, latim, grego, ciências, religião e desenho. Goethe teve aulas de violoncelo e piano, além de dança e equitação. O contato com a literatura se deu desde a infância, através das histórias contadas por sua mãe e da leitura da Bíblia. A família tinha uma biblioteca que continha mais de 2000 volumes.

Juventude: Estudos e primeiras produções literárias[editar | editar código-fonte]

Por decisão de seu pai, Goethe iniciou os estudos na Faculdade de Direito de Leipzig em 1765, mostrando-se, porém, pouco interessado. Goethe dedicou-se mais às aulas de desenho, xilogravura e gravura em metal, e aproveitava a vida longe da casa dos pais entre teatros e noites na boémia. Acometido por uma doença, possivelmente tuberculose, voltou para a casa dos pais. Em 1769 Goethe publicou sua primeira antologia, Neue Lieder.

Em 1768, retorna para Frankfurt am Main a fim de recuperar a saúde debilitada. Enquanto se recupera, dedica-se a leituras, experiências com alquimia e astrologia. Nesse mesmo ano, Goethe escreve sua primeira comédia: Die Mitschuldigen. Em abril de 1770 volta aos estudos de direito, agora em Estrasburgo, Alsácia, dessa vez mostrando-se mais interessado. Durante esse período, conheceu Johann Gottfried Herder. Teólogo e estudioso das artes e da literatura, Herder influenciou Goethe trazendo a ele leituras como Homero, Shakespeare e Ossian assim como o contato com a poesia popular (Volkspoesie).

Nesse período, Goethe escrevia poemas a Friederike Brion, com a qual mantinha um romance. Esses, mais tarde, ficaram conhecidos como Sesenheimer Lieder. Nelas já se expressa fortemente o início de uma nova produção literária lírica.

No verão de 1771, Goethe licencia-se na faculdade de direito.

Sturm und Drang (Tempestade e Ímpeto)[editar | editar código-fonte]

De volta a Frankfurt am Main, Goethe trabalha sem muito ânimo em seu escritório de advocacia, dando maior importância à poesia. Ao fim de 1771 escreveu Geschichte Gottfriedens von Berlichingen mit der eisernen Hand, que veio a ser publicado dois anos depois sob o título Götz Von Berlichtungen (O cavaleiro da mão de ferro). A peça veio a valer como a primeira obra do movimento Sturm und Drang (Tempestade e Ímpeto).

Em 1772 Goethe mudou-se para Wetzlar, a pedido do pai, para trabalhar na sede da corte da justiça imperial. Lá conheceu Charlotte Buff, noiva de seu colega Johann Christian Kestner, por quem se apaixonou. O escândalo dessa paixão obrigou-o a deixar Wetzlar. Um ano e meio depois, em 1774, Goethe publica Die Leiden des Jungen Werther (Os Sofrimentos do Jovem Werther). Com esse romance Goethe tornou-se rapidamente conhecido em toda a Europa.

O período entre seu retorno de Wetzlar e a partida à Weimar foi um dos mais produtivos de sua carreira. Além de Werther, Goethe escreveu, entre outros, poemas que se tornaram exemplares de sua obra como Prometheus, Ganymed e Mahomets Gesang, além de peças como Clavigo (Clavigo),Stella, e outras mais curtas como Götter, Helden und Wieland. Nesse período Goethe inicia o projeto de seu mais conhecido escrito,Faust (Fausto).

Em Weimar[editar | editar código-fonte]

Em 1775, Carlos Augusto herda o governo de Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach e convida Goethe a visitar a Weimar, capital do ducado. Disposto a desfrutar os prazeres da corte, Goethe aceita o convite a acaba por mudar-se para Weimar[1]. Em pouco tempo a população o acusa de desencaminhar o príncipe, que por sua vez reage e faz Goethe comprometer-se com setores do governo. Goethe passa então, como ministro, a exercer alguns serviços administrativos, como inspecionar minas e irrigação do solo, entre outros. Goethe viveu até 1786 na cidade, onde veio a exercer diversas funções político-administrativas[3]. Em Weimar, Goethe viveu um afetuoso romance com Charlotte von Stein, do qual restaram documentados mais de 2 mil cartas e bilhetes.

Com o trabalho diário na administração da cidade restava-lhe pouco tempo para sua prática poética. Nesse período Goethe trabalha na escrita em prosa de Iphigenie auf Tauris (Ifigênia em Táuride), além de Egmont, Torquarto Tasso e Os Anos de Aprendizado de Wilhelm Meister, e dos poemas Wandrers Nachtlied, Grenzen der Menschheit e Das Göttliche.

Por volta de 1780, Goethe passa a ocupar-se sistematicamente com pesquisas na área das ciências naturais. Seu interesse demonstrou-se principalmente nas áreas de geologia, botânica e osteologia. No mesmo ano, juntamente com Herder, torna-se membro de uma sociedade secreta, os Illuminati (conhecida como Maçonaria Iluminada[4], extinta pelo governo da Baviera em 1787), que alcança grande prestígio entre as elites europeias.

Viagem à Itália[editar | editar código-fonte]

Goethe estava cada vez mais insatisfeito com trabalho na administração pública e seu relacionamento com Charlotte se desgastou. Goethe entrou em crise com relação ao rumo tomado por sua vida. Por conta disso, em 1786, partiu sem pré-aviso para a Itália usando um pseudônimo, evitando assim ser reconhecido, já que na época já havia se tornado um autor famoso. Goethe passou por Verona, Veneza, Lago di Garda, até chegar a Roma, onde permanece até 1788, tendo também visitado nesse meio tempo Nápoles e Sicília[1]. Em abril daquele ano, Goethe deixou Roma e chegando dois meses depois de volta em Weimar.

Na Itália, Goethe conheceu e encantou-se pelas construções e obras de arte da antiguidade clássica e do Renascimento, admirava em especial os trabalhos de Rafael e Andrea Palladio. Lá se dedicou ao desenho, decidindo-se porém pela profissão de poeta. Entre outras coisas Goethe versificou nesse período Iphigenie auf Tauris (Ifigênia em Tauride), finalizou Egmont, doze anos após o iniciado da escrita desse, e deu prosseguimento a Tasso.

A viagem fora para Goethe uma experiência restabelecedora.

Classicismo de Weimar[editar | editar código-fonte]

De volta a Weimar, trava amizade com Johanna Schopenhauer, mãe do filósofo Arthur Schopenhauer. Poucas semanas após o retorno, Goethe conhece Christiane Vulpius, uma mulher de 23 anos, de origem simples, sem prestígio social. Mesmo com a pouca aceitação da sociedade weimarense, Goethe e Christiane casam-se em 1806, mesmo ano que a cidade foi invadida pelos franceses em ocasião da expansão napoleônica. O casal permaneceu junto até a morte dela em 1816.

Goethe assume cargos de influência política nas áreas de cultura e científica. De 1791 a 1817 Goethe dirigiu o teatro de Weimar, antes dirigira a escola de desenho. Ao mesmo tempo Goethe era membro conselheiro na Universidade de Jena, onde conheceu, entre outros, Friedrich Schiller, Georg Hegel e Friedrich Schelling.

Em 1794, inicia amizade com Friedrich von Schiller, que passa também a residir em Weimar. Essa amizade entre os dois grandes escritores é celebrada como um dos maiores momentos da literatura alemã.

Ciências naturais e poesia[editar | editar código-fonte]

Em 1806, Weimar é invadida pelos franceses e Goethe casa-se com Christiane Vulpius. Nos anos posteriores à sua viagem à Itália, Goethe empenhava-se em pesquisas nas ciências naturais. Em 1790 ele publica obra chamada Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären, e inicia sua pesquisa sobre as cores, assunto ao qual se dedicou até o fim de sua vida.[1]

As obras da década de 1790 fazem parte Römische Elegien, uma coleção de poemas eróticos à maneira clássica sobre a paixão de Goethe por Christiane. Da viagem à Itália vieram os Venetiatischen Epigrame, poemas satíricos sobre a Europa da época. Goethe escreveu também uma série de comédias satirizando a Revolução Francesa: Der Groβ-Cophta (1791), Der Bürgergeneral (1793), e o fragmento Die Aufgeregten (1793).

Em 1794 Schiller convida Goethe para colaborar na revista de arte e cultura: Die Horen. Goethe aceita o convite e a partir daí inicia-se uma aproximação entre os dois intelectuais, que resultou numa íntima amizade. Ambos desaprovavam a Revolução e apoiavam a estética da antiguidade clássica como ideal artístico.

Como resultado de suas discussões a respeito dos fundamentos estéticos da arte, Schiller e Goethe desenvolveram ideias artísticas que deram origem ao Classicismo de Weimar.

Nesse período, Schiller convence Goethe a retomar a escrita de Faust (Fausto) e acompanha o nascimento de Wilhelm Meister Lehrjahre (Os Anos de Aprendizado de Wilhelm Meister). Além dessas obras, Goethe escreve no mesmo período Unterhaltungen deutscher Ausgewanderten e o épico escrito em hexâmetro clássico Hermann und Dorothea.

Em 1805, interfere para que Hegel seja nomeado professor na Universidade de Berlim. A morte de Schiller nesse mesmo ano, foi uma grande perda para o amigo Goethe,

Em 1808, Napoleão condecora Goethe, no Congresso de Erfurt, com a grande cruz da Legião da Honra. De acordo com sua correspondência, sobretudo os registros de Eckermann, seu amigo, Goethe ficou bastante aturdido com a Revolução Francesa. Prova disso é a segunda parte de Fausto, publicada postumamente, conforme carta ao amigo, ao qual dizia para só se abrir o pacote após sua morte, num profundo lamento, prevendo que sua literatura seria deixada no esquecimento.

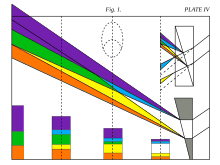

Nesse período Goethe faz incursões pela ciência e publica algumas obras a esse respeito. A Teoria das Cores é publicada em 1810.

Últimos anos do poeta[editar | editar código-fonte]

Nos anos que seguiram a morte de Schiller, Goethe adoece diversas vezes. Em 1806, ano em que Goethe se casa com Christiane Vulpius, Weimar é invadida pelas tropas de Napoleão. Atormentado com os acontecimentos, Goethe vive uma fase pessimista. Desta época provém seu último romance, Die Wahlverwandschaften, de 1809. Um ano depois Goethe começa a escrever sua autobiografia e publica Teoria das Cores.

Um ano após a morte da esposa (1816), Goethe organiza seus escritos e publica os trabalhos: Geschichte meines botanischen Studiums (1817); Italianischen Reise (1817) (Viagem à Itália), diário e reflexões de sua viagem, em duas partes, respectivamente; Wilhelm Meister Wanderjahre (1821) e Zur Naturwissenschaft überhaupt (1824). Em 1823, Jean-Pierre Eckerman torna-se secretário de Goethe e o ajuda na revisão e publicação de escritos até sua morte. As conversações com Eckerman são fruto dessa colaboração.

Durante esse período Goethe dedicava-se à escrita de Faust, que veio a finalizar, após 16 anos de trabalho, em 1830. Aos 82 anos, em 22 de março de 1832, Goethe morre na cidade de Weimar. Encontra-se sepultado no Cemitério Histórico de Weimar, Turíngia na Alemanha[5] ao lado de Friedrich Schiller.

Recepção da obra[editar | editar código-fonte]

Goethe se torna conhecido em toda a Europa na ocasião da publicação de Os Sofrimentos do Jovem Werther. Já no século XIX, Goethe torna-se parte do cânone literário, sendo parte do currículo escolar desde 1860.

Goethe foi aclamado gênio no Segundo Reich e suas ideias foram fundamentais para a instauração da República de Weimar, após a Primeira Guerra Mundial. Já no na Alemanha Nazista, sua obra fora deixada de lado, pois suas ideias humanistas não cooptavam com a ideologia nazista.

Goethe no Brasil[editar | editar código-fonte]

Grande interessado em culturas, Goethe não deixou de observar aspectos da cultura brasileira. Em sua biblioteca constavam 17 títulos de obras que tratavam do Brasil, além de estarem registrados empréstimos de livros do tema na biblioteca de Weimar. Goethe conheceu canções tupinambás através da leitura de Dos Canibais de Montaigne e mantinha um intercâmbio de informações científico com Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, a quem costumava chamar de o "brasileiro" Martius. Esse e Ness Von Esenbeck o homenagearam batizando de Goetha uma espécie de malvácea brasileira.

Na literatura, Goethe influenciou autores de renome como Machado de Assis e Guimarães Rosa.

Curiosidades[editar | editar código-fonte]

Se(c)ções de curiosidades são desencorajadas pelas políticas da Wikipédia. (Dezembro de 2009) |

- O "método" goethiano de análise fenomenológica não se restringia à botânica, mas também abrange a teoria do conhecimento e a das cores. No início do século XX, o filósofo austro-húngaro Rudolf Steiner fundou a Ciência Espiritual, ou Antroposofia, inspirado no método de observação dos fenômenos desenvolvido por Goethe (no qual a parte subjetiva do observador é também considerada).

- Goethe passou anos obcecado pela obra Da Teoria das Cores, em que propunha uma nova teoria das cores, em oposição à teoria de Newton. Essa obra por muito tempo foi deixada de lado, em boa parte devido à maneira violenta pela qual pretende provar que Newton estava errado. Goethe fez diversas observações corretas sobre a natureza das cores, especialmente sobre o aspecto da percepção emocional e psicológica, que serão retomadas anos mais tarde pela escola da Gestalt e não ferem a teoria de Newton, mas tentou justificá-las com argumentos falaciosos. Esses argumentos fizeram-no cair em descrença na comunidade científica.

Obras (seleção)[editar | editar código-fonte]

Dramas[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Die Laune des Verliebten (1768)

- Die Mitschuldigen (1768-1769)

- Götz von Berlichingen (primeira versão 1771, versão definitiva 1773)

- Clavigo (1774)

- Urfaust (Fausto Zero) (1775)

- Stella (1775)

- Egmont (1775-1788)

- Iphigenie auf Tauris (1779-1786)

- Torquato Tasso (1780)

- Der Gross-Cophta (1791)

- Der Bürgergeneral (1793)

- Die Aufgeregten (Fragmento, 1793)

- Das Mädchen von Oberkirch (fragmento, 1795/96)

- Die natürliche Tochter (1801-1803)

- Fausto I (1806)

- Fausto II (1832, publicação póstuma)

Romances e novelas[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Os Sofrimentos do Jovem Werther (1774)

- Wilhelm Meisters theatralische Sendung (1777-1785)

- Reise der Söhne Megaprazons (fragmento, 1792)

- Unterhaltungen Deutscher Ausgewanderten (1795)

- Os Anos de Aprendizado de Wilhelm Meister (1796-1797)

- As Afinidades Eletivas (1809)

- Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre (primeira versão 1821, segunda versão 1829)

- Novela (1826-1827)

Épicas[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Reineke-Fuchs (1793)

- Hermann e Dorotéia (1796-1797)

Poemas[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Prometheus (1774)

- O Aprendiz de Feiticeiro (poema) (1797)

- West-östlicher Divan (primeira versão 1819/ versão ampliada 1827)

Escritos científicos[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Teoria das Cores (1810)

Prosa autobiográfica[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Aus meinem Leben. Dichtung und Wahrheit (1811-1833)

- Viagem à Itália (1813-1817)

- Kampagne in Frankreich 1792 (1819-1822)

Textos traduzidos[editar | editar código-fonte]

- ___. O cavaleiro da mão de ferro (Götz von Berlichingen). Trad. Armando Lopo Simeão. Lisboa: Edições Ultramar, 1945.

- ___. Egmont; Tragédia em cinco atos. Trad. Hamilcar Turelli. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1949.

- ___. Clavigo; Tragédia. Trad. Carlos Alberto Nunes. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1949.

- ___. Ifigênia em Táuride; Drama. Trad. Carlos Alberto Nunes. São Paulo: Instituto Hans Staden, 1964.

- ____. Memórias: Poesia e Verdade. Tradução de Leonel Vallandro. Porto Alegre: Globo, 1971 (reeditada pela Editora da Universidade de Brasília / HUCITEC, 1986).

- ____. Os anos de aprendizado de Wilhelm Meister. Tradução: Nicolino Simone Neto. São Paulo: Ensaio, 1994.

- ___. Torquato Tasso: um drama. Tradução de João Barrento. Prefácio de Maria Filomena Molder Lisboa: Relógio D'água, 1999.

- ____. Raineke-Raposo. São Paulo. Adaptação em prosa. Tradução: Tatiana Belinky. São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1998.

- ____. Escritos sobre literatura. Seleção e Tradução: Pedro Süssekind. Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2000.

- ___. Fausto zero. Trad. Christine Röhrig. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 2001.

- ___. Fausto e Werther. Trad. Alberto Maximiliano. São Paulo: Nova Cultural, 2002.

- ___. Fausto I: Uma tragédia (Primeira parte). Apresentação, comentários e notas de Marcus Mazzari. Trad. Jenny Klabin Segall. Edição bilíngue. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2004.

- ____. Novela. São Paulo. Editora 7Letras, 2004.

- ___. Fausto. Trad. Agostinho D'Ornellas. São Paulo: Martin Claret, 2004. [inclui a Primeira e Segunda Partes de Faust]

- ___. Escritos sobre arte. Introdução, tradução e notas de Marco Aurélio Werle. São Paulo: Associação Editorial Humanitas / Impressãoficial, 2005.

- ____. O Aprendiz De Feiticeiro. Tradução: Mônica Rodrigues da Costa. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006.

- ___. Fausto II: Segunda parte da tragédia. Apresentação, comentários e notas de Marcus Mazzari. (Trad. Jenny Klabin Segall. Edição bilíngue. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2007.

- ____. Os Sofrimentos Do Jovem Werther. São Paulo: Martins Editora, 2007.

- ____. Goethe e Hackert – Sobre a Pintura de Paisagem. Tradução e seleção: Claudia Valladão de Mattos. São Paulo: Atelie Editorial, 2008.

- ____. As Afinidades Eletivas. Tradução: Leonardo Froes. São Paulo: Nova Alexandria, 2008.

- ____. Escritos Sobre Arte. Tradução: Marco Aurélio Werle. São Paulo: Imesp, 2008.

- ____. Trilogia Da Paixao. Edição Bilíngue. Tradução: Erlon José Paschoal. Porto Alegre: L&PM Editores, 2009.

- ____. Os anos de aprendizado de Wilhelm Meister. São Paulo: Editora, 34, 2009.

- ____. Correspondência entre Goethe e Schiller. Tradução e seleção: Claudia Cavalcanti. São Paulo: Hedra, 2010.

- ____. Ensaios científicos: uma metodologia para o estudo da natureza. Coletânea. Tradução: Jacira Cardoso. Introdução de Antonio José Marques. São Paulo: Ad Verbum Editorial / Barany, 2012.

- ____. "O conto da serpente verde e da linda Lilie". [Tradução de Märchen]; trad. e posfácio de Roberto Cattani. Comentários de Oswald Wirth. São Paulo: Aquariana, 2012 (Coleção Vasto Mundo).

- ____. "As afinidades Eletivas". Tradução Tercio Redondo. São Paulo: Penguim / Companhia das Letras, 2014.

- ____. A criada de Oberkirch. Tradução por Felipe Vale da Silva. Revista In-Traduções, Florianópolis, v. 7, 2015, p. 49-56.

- ____ & ECKERMANN, J. P. "Conversações com Goethe nos últimos anos de sua vida". Tradução por Mário Luiz Frungillo. São Paulo: Editora da UNESP, 2016.

Citações[editar | editar código-fonte]

Fausto

"Se eu me acosto jamais em fofa cama,

contente e em paz, que nesse instante eu morra!

Se uma só vez com falsas louvaminhas

chegares por tal arte a alucinar-me

que eu me agrade a mim próprio; se valeres

a cativar-me com deleites frívolos,

súbito a luz da vida se me apague.

Vá! queres apostar?"

Quadro V, Cena I - Tradução António Feliciano de Castilho

Referências

- ↑ a b c d e «Johann Wolfgang von Goethe - Biografia». Enciclopédia Mirador Internacional. UOL - Educação. Consultado em 27 de agosto de 2012

- ↑ Grimm, Herman: Goethe. Vorlesungen gehalten an der Königlichen Universität zu Berlin. Vol. 1. J. G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger, Stuttgart / Berlin 1923, p. 36

- ↑ Charlotte Von Stein. Classic Encyclopedia, (em inglês) Página visitada em 27 de agosto de 2012.

- ↑ Froés, Leonardo (2010). Trilogia da paixão (em alemão e português) 2009 ed. Porto Alegre, RS: L&PM. 129 páginas. ISBN 978-85-254-1888-3

- ↑ Lucas Brandão/Testes (em inglês) no Find a Grave

Bibliografia sobre Goethe[editar | editar código-fonte]

- ÁVILA, Myriam. A pedra flexível do discurso: imagens do Brasil na Alemanha de Goethe. Abralic. Salvador, v. 5, p. 65-75, 2000.

- BARTHES, Roland. Fragmentos de um discurso amoroso. Trad. Hortência dos Santos. 4. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Francisco Alves, 1984.

- BENTLEY, Eric. O dramaturgo como pensador. Trad. Ana Zelma Campos. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1991, p. 99-108.

- BERMAN, Antoine. L'épreuve de l'étranger. Culture et traduction dans l'Allemagne romantique: Herder, Goethe, Schlegel, Novalis, Humboldt, Schleiermacher, Hölderlin. París: Gallimard, 1984. ISBN 978-2070700769.

- BOLLE, Willi. Seja homem e não me siga… [Posfácio]. In: GOETHE, Wolfgang. Os sofrimentos do jovem Werther. Trad. Leonardo César Lack. São Paulo: Nova Alexandria, 1999. p. 137-144.

- BORNHEIM, Gerd A. O sentido e a máscara. 2. ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1969. (Debates, 8).

- BROCA, Brito. A viagem maravilhosa de Goethe. In: ___. Ensaios da mão canhestra. Prefácio de Antonio Candido. São Paulo: Polis / Brasília: INL, 1981. (Coleção Estética: Série obras reunidas de Brito Broca, 11).

- ___. Sobre os amores de Goethe. In: ___. Escrita e vivência. Campinas: Edunicamp, 1993. (Coleção Repertórios). p. 200-202.

- CAMPOS, Haroldo de. Deus e o diabo no Fausto de Goethe. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981. (Signos, 9).

- CARPEAUX, Otto Maria. Presença de Goethe. In: ___. A cinza do purgatório; Ensaios. Casa do estudante Brasileiro, 1942. p. 27-36.

- CITATI, Pietro. Goethe. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- D’ONOFRIO, Salvatore. Literatura ocidental; Autores e obras fundamentais. 2. ed. São Paulo: Ática, 1997. p. 365-376.

- FRANSBACH, Martin. Gonçalves Dias ‘Canção do exílio’ und Goethes ‘Mignon’ – Interpretation und Quellenvergleich. Revista de Letras. Assis (UNESP), v. 6, p. 119-128, 1965.

- HARTL, Ingeborg. Goethe e a RDA nos anos 70 na obra ‘Die neuen Leiden des jungen W.’ de Ulrich Plenzdorf. forum deutsch. Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), v. 4, p. 45-57, 2000.

- HEISE, Eloá. Goethe, um teórico da transnacionalidade. Abralic. Salvador, v. 5, p. 77-84, 2000.

- HOLANDA, Sérgio Buarque de. O Fausto. In: ___. O espírito e a letra. Org. introd. e notas Antônio Arnoni Prado. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1996, v. 1, p. 77-89.

- JACOBBI, Ruggero. Goethe, Schiller, Gonçalves Dias. Porto Alegre: Edições da Faculdade de Filosofia da Universidade do Rio Grande do Sul, 1958.

- KESTLER, Izabela Furtado. O período da arte (Kunstperiode): Convergências entre Classicismo e a primeira fase do Romantismo alemão. forum deutsch. Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), v. 4, p. 73-86, 2000.

- MAAS, Wilma Patrícia Dinardo. Sobre a criação e circulação do termo ‘Bildungsroman’ (romance de formação). Anais do IV Congresso ABRALIC – Literatura e Diferença. São Paulo, p. 1081-1085, 1995.

- ___. As diversas faces de Wilhelm Meister. O Estado de S. Paulo. São Paulo, 5 nov. 1994. Caderno Cultura, p. Q-8.

- ___. Poesia e verdade, de Goethe – a estetização da existência. Cerrados. Brasília (UnB), v. 9, p. 165-177.

- ___. O cânone mínimo: o “Bildungsroman” na história da literatura. São Paulo: Editora da UNESP, 2000.

- MASON, Jayme. O dr. Fausto e seu pacto com o diabo; O Fausto histórico, o Fausto lendário e o Fausto literário. Rio de janeiro: Objetiva, 1989.

- MATOS, Franklin. O Solilóquio de Werther. In: WERLE, M. A. & GALÉ, P. F. Arte e Filosofia no Idealismo Alemão. São Paulo: Editora Barcarolla, 2009, 141-150.

- MATTOS, Delton de. A linguagem do Fausto de Goethe (1ª parte). Um ensaio sobre a forma poética. Brasília: Thesaurus, 1986.

- MERQUIOR, José Guilherme. Crítica 1964-1989; Ensaios sobre arte e literatura. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1990.

- MEYER, Augusto. O rei de Tule. In: A forma secreta. Rio de Janeiro: Lidador, 1965.

- MONTEZ, Luiz. Conhecimento e alienação no Fausto de Goethe. Terceira Margem. Rio de Janeiro (Revista da Pós-Graduação da Faculdade de Letras da UFRJ), n. 4, p. 34-41, 1996.

- ___. O século XVIII e o Pré-Romantismo. Tempo Brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro, n. 127, p. 99-110, 1996.

- __. A obra autobiográfica de Goethe como relato historiográfico. Itinerários (UNESP), v. 23, 2005, p. 39-48.

- __. Literatura e Vida: Relembrando um Goethe um Tanto Esquecido. Terceira Margem, Rio de Janeiro, v. 10, 2004, p. 170-185.

- __. Sobre o mito do Goethe. Forum Deustch - Revista Brasileira de Estudos Germanísticos, Faculdade de Letras da UFRJ, v. 6, 2002, p. 88-102.

- __. Sob a ética do olhar, do tempo e da escrita. Goethe e a história. In: Catharina, Pedro Paulo Garcia Ferreira; Mello, Celina Maria Moreira de. (Org.). Cenas da Literatura Moderna. 1ed.Rio de Janeiro: Editora 7 Letras, 2010, v. , p. 191-216.

- __. Sobre a atualidade do "classicismo" alemão: a interpretação lukacsiana de Goethe. In: Celina Maria Moreira de Mello; Pedro Paulo Garcia Ferreira Catharina. (Org.). Crítica e Movimentos Estéticos. Configurações Discursivas do Campo Literário. 1ed.Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2006, v. , p. 189-207.

- ORGANON. Revista do Instituto de Letras da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre, v. 6, n. 19 (O pacto fáustico e outros pactos), 1992.

- ORLANDI, Enzo (Dir.). Goethe. Trad. Yvette Kace Centeno e G. Martins de Oliveira. Lisboa: Editorial Verbo, 1972. (Gigantes da Literatura Universal, 16).

- ROSA, Elis Piera. O símbolo e alegoria nos textos teóricos de Goethe, de 1772 a 1798. Dissertação (Mestrado), Araraquara, 2012.

- ROSENFELD, Anatol. Teatro moderno. 2. ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva,1985. (Debates, 153).

- ___. Introdução – Da Ilustração ao romantismo. In: HAMANN, J. G. et al. Autores pré-românticos alemães. Trad. João Marschner, Flávio Meurer e Lily Strehler. Introd. e notas Anatol Rosenfeld. 2. ed. São Paulo: EPU, 1991. p. 7-24.

- ___. Texto/contexto II. São Paulo: Perspectiva / Edusp; Campinas: Edunicamp, 1993. (Debates, 257).

- SALEMA, Teresa. De ‘Werther’ a ‘Wilhelm Meister’ ou Uma aprendizagem da economia do génio. Colóquio Letras. Lisboa, v. 74, p. 5-14, jul. 1983.

- SCHUBACK, Marcia Sa Cavalcante. A doutrina dos sons de Goethe a caminho da música nova de Webern. Seleção, tradução e comentários Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback. Com o ensaio “Composição e natureza”, de Rodolfo Caesar. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. UFRJ, 1999.

- SEEHAFER, Klaus: Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe. Dichter, Naturforscher, Staatsmann. 1749-1832. Bonn, 1999

- SILVA, Felipe Vale da. Subjetividade e Experiência em Die Leiden des jungen Werthers e Wilhelm Meisters theatralische Sendung de J. W. Goethe. Dissertação (Mestrado). São Paulo, 2012. 220 p.

- ___. Die Leiden des jungen Werthers à Luz da História do Conceito de Subjetividade. Pandaemonium Germanicum, São Paulo, v. 16, n. 21, Jun/2013, p. 79-110.

- ___. Das Mädchen von Oberkirch, de J. W. von Goethe: Tradução e Comentários. In-Traduções, Florianópolis, v. 7, 2015,p. 41-65.

- ___. A ficção histórica de Goethe: do Sturm und Drang à Revolução Francesa. Tese (Doutorado). São Paulo, 2016. 355 p.

- SOETHE, Paulo Astor. O Brasil na obra de Goethe. forum deutsch. Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), v. 4, p. 26-44, 2000.

- SUZUKI, Yumi. Os sofrimentos do jovem Werther sob o signo da subjetividade :uma abordagem filosófico-literária. Dissertação (Mestrado). São Paulo, 1999. 119 p.

- THEODOR, Erwin. Perfis e sombras; Estudos de literatura alemã. São Paulo: EPU, 1990.

Ver também[editar | editar código-fonte]

Ligações externas[editar | editar código-fonte]

- «Obras de Johann Wolfgang Goethe» (em alemão) no Zeno.org

- «Lista das obras de Goethe» (em alemão)

- «Biografia» (em alemão) na Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie

- «Interesses de Goethe no Brasil» (em alemão)

- «Tradução de Novella por Thomas Carlyle e R.D. Boylan» (em inglês)

- «Tradução inglesa de Dichtung und Wahrheit, parte 1» (em inglês) (The Autobiography of Goethe: Truth and Poetry, from My Own Life vol 1) (1848)

- «Tradução inglesa de Dichtung und Wahrheit, parte 2» (em inglês) (The Autobiography of Goethe: Truth and Poetry, from My Own Life vol 2) (1881)

- «Edição inglesa das obras de Goethe de 1839, disponível em pdf» (em inglês)

- «Diversas obras de Goethe em Online-Literature.com» (em inglês)

- «Links para 61 obras em diversos idiomas»

- «Goethe como pensador na Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy» (em inglês)

- «Goethe como educador no Wilhelm Meister»

- «Diversas traduções de poemas» (em inglês)

- «Poemas traduzidos em Poems Found in Translation» (em inglês)

- Obra de J. W. Goethe em audiobook em Librivox.org (em alemão e inglês)

Predefinição:Redirect2

Predefinição:Use dmy dates

Predefinição:Infobox writer

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe ( /ˈɡɜːrtə/;[1][2][3] alemão: [ˈjoːhan ˈvɔlfɡaŋ ˈɡøːtə] (ⓘ); 28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German writer and statesman. His body of work includes epic and lyric poetry written in a variety of metres and styles; prose and verse dramas; memoirs; an autobiography; literary and aesthetic criticism; treatises on botany, anatomy, and colour; and four novels. In addition, numerous literary and scientific fragments, more than 10,000 letters, and nearly 3,000 drawings by him exist.

A literary celebrity by the age of 25, Goethe was ennobled by the Duke of Saxe-Weimar, Karl August in 1782 after taking up residence there in November 1775 following the success of his first novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther. He was an early participant in the Sturm und Drang literary movement. During his first ten years in Weimar, Goethe was a member of the Duke's privy council, sat on the war and highway commissions, oversaw the reopening of silver mines in nearby Ilmenau, and implemented a series of administrative reforms at the University of Jena. He also contributed to the planning of Weimar's botanical park and the rebuilding of its Ducal Palace, which in 1998 were together designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[4]

His first major scientific work, the Metamorphosis of Plants, was published after he returned from a 1788 tour of Italy. In 1791, he was made managing director of the theatre at Weimar, and in 1794 he began a friendship with the dramatist, historian, and philosopher Friedrich Schiller, whose plays he premiered until Schiller's death in 1805. During this period, Goethe published his second novel, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship, the verse epic Hermann and Dorothea, and, in 1808, the first part of his most celebrated drama, Faust. His conversations and various common undertakings throughout the 1790s with Schiller, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Johann Gottfried Herder, Alexander von Humboldt, Wilhelm von Humboldt, and August and Friedrich Schlegel have, in later years, been collectively termed Weimar Classicism.

Arthur Schopenhauer cited Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship as one of the four greatest novels ever written, along with Tristram Shandy, La Nouvelle Héloïse, and Don Quixote,[5] and Ralph Waldo Emerson selected Goethe as one of six "representative men" in his work of the same name, along with Plato, Napoleon, and William Shakespeare. Goethe's comments and observations form the basis of several biographical works, most notably Johann Peter Eckermann's Conversations with Goethe. There are frequent references to Goethe's writings throughout the works of Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Oswald Spengler, Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, Sigmund Freud, and Carl Jung. Goethe's poems were set to music throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by a number of composers, including Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Charles Gounod, Richard Wagner, Hugo Wolf, Felix Mendelssohn, Hector Berlioz, Gustav Mahler, and Jules Massenet.

Biography[editar | editar código-fonte]

Early life[editar | editar código-fonte]

Goethe's father, Johann Caspar Goethe, lived with his family in a large house in Frankfurt, then an Imperial Free City of the Holy Roman Empire. Though he had studied law in Leipzig and had been appointed Imperial Councillor, he was not involved in the city's official affairs.[6] Johann Caspar married Goethe's mother, Catharina Elizabeth Textor at Frankfurt on 20 August 1748, when he was 38 and she was 17.[7] All their children, except for Goethe and his sister, Cornelia Friederica Christiana, who was born in 1750, died at early ages.

His father and private tutors gave Goethe lessons in all the common subjects of their time, especially languages (Latin, Greek, French, Italian, English and Hebrew). Goethe also received lessons in dancing, riding and fencing. Johann Caspar, feeling frustrated in his own ambitions, was determined that his children should have all those advantages that he had not.[6]

His great passion was drawing. Goethe quickly became interested in literature; Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock and Homer were among his early favourites. He had a lively devotion to theatre as well and was greatly fascinated by puppet shows that were annually arranged in his home; a familiar theme in Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship.

He also took great pleasure in reading from the great works about history and religion. He writes about this period:

I had from childhood the singular habit of always learning by heart the beginnings of books, and the divisions of a work, first of the five books of Moses, and then of the 'Aeneid' and Ovid's 'Metamorphoses'. . . If an ever busy imagination, of which that tale may bear witness, led me hither and thither, if the medley of fable and history, mythology and religion, threatened to bewilder me, I readily fled to those oriental regions, plunged into the first books of Moses, and there, amid the scattered shepherd tribes, found myself at once in the greatest solitude and the greatest society.[8]

Goethe became acquainted with Frankfurt actors.[9] Around early literary attempts, he was infatuated with Gretchen, who would later reappear in his Faust and the adventures with whom he would concisely describe in Dichtung und Wahrheit.[10] He adored Caritas Meixner (27 July 1750 – 31 December 1773), a wealthy Worms trader's daughter and friend of his sister, who would later marry the merchant G. F. Schuler.[11]

Legal career[editar | editar código-fonte]

Goethe studied law at Leipzig University from 1765 to 1768. He detested learning age-old judicial rules by heart, preferring instead to attend the poetry lessons of Christian Fürchtegott Gellert. In Leipzig, Goethe fell in love with Anna Katharina Schönkopf and wrote cheerful verses about her in the Rococo genre. In 1770, he anonymously released Annette, his first collection of poems. His uncritical admiration for many contemporary poets vanished as he became interested in Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Christoph Martin Wieland. Already at this time, Goethe wrote a good deal, but he threw away nearly all of these works, except for the comedy Die Mitschuldigen. The restaurant Auerbachs Keller and its legend of Faust's 1525 barrel ride impressed him so much that Auerbachs Keller became the only real place in his closet drama Faust Part One. As his studies did not progress, Goethe was forced to return to Frankfurt at the close of August 1768.

Goethe became severely ill in Frankfurt. During the year and a half that followed, because of several relapses, the relationship with his father worsened. During convalescence, Goethe was nursed by his mother and sister. In April 1770, Goethe left Frankfurt in order to finish his studies at the University of Strasbourg.

In Alsace, Goethe blossomed. No other landscape has he described as affectionately as the warm, wide Rhine area. In Strasbourg, Goethe met Johann Gottfried Herder. The two became close friends, and crucially to Goethe's intellectual development, Herder kindled his interest in Shakespeare, Ossian and in the notion of Volkspoesie (folk poetry). On 14 October 1772 Goethe held a gathering in his parental home in honour of the first German "Shakespeare Day". His first acquaintance with Shakespeare's works is described as his personal awakening in literature.[12]

On a trip to the village Sessenheim, Goethe fell in love with Friederike Brion, in October 1770,[13][14] but, after ten months, terminated the relationship in August 1771.[15] Several of his poems, like "Willkommen und Abschied", "Sesenheimer Lieder" and "Heidenröslein", originate from this time.

At the end of August 1771, Goethe acquired the academic degree of the Lizenziat (Licentia docendi) in Frankfurt and established a small legal practice. Although in his academic work he had expressed the ambition to make jurisprudence progressively more humane, his inexperience led him to proceed too vigorously in his first cases, and he was reprimanded and lost further ones. This prematurely terminated his career as a lawyer after only a few months. At this time, Goethe was acquainted with the court of Darmstadt, where his inventiveness was praised. From this milieu came Johann Georg Schlosser (who was later to become his brother-in-law) and Johann Heinrich Merck. Goethe also pursued literary plans again; this time, his father did not have anything against it, and even helped. Goethe obtained a copy of the biography of a noble highwayman from the German Peasants' War. In a couple of weeks the biography was reworked into a colourful drama. Entitled Götz von Berlichingen, the work went directly to the heart of Goethe's contemporaries.

Goethe could not subsist on being one of the editors of a literary periodical (published by Schlosser and Merck). In May 1772 he once more began the practice of law at Wetzlar. In 1774 he wrote the book which would bring him worldwide fame, The Sorrows of Young Werther. The outer shape of the work's plot is widely taken over from what Goethe experienced during his Wetzlar time with Charlotte Buff (1753–1828)[16] and her fiancé, Johann Christian Kestner (1741–1800),[16] as well as from the suicide of the author's friend Karl Wilhelm Jerusalem (1747–1772); in it, Goethe made a desperate passion of what was in reality a hearty and relaxed friendship.[17] Despite the immense success of Werther, it did not bring Goethe much financial gain because copyright laws at the time were essentially nonexistent. (In later years Goethe would bypass this problem by periodically authorizing "new, revised" editions of his Complete Works.)[18]

Early years in Weimar[editar | editar código-fonte]

In 1775, Goethe was invited, on the strength of his fame as the author of The Sorrows of Young Werther, to the court of Carl August, Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, who would become Grand Duke in 1815. (The Duke at the time was 18 years of age, to Goethe's 26.) Goethe thus went to live in Weimar, where he remained for the rest of his life and where, over the course of many years, he held a succession of offices, becoming the Duke's chief adviser.

In 1776, Goethe formed a close relationship to Charlotte von Stein, an older, married woman. The intimate bond with Frau von Stein lasted for ten years, after which Goethe abruptly left for Italy without giving his companion any notice. She was emotionally distraught at the time, but they were eventually reconciled.[19]

Goethe, aside from official duties, was also a friend and confidant to the Duke, and participated fully in the activities of the court. For Goethe, his first ten years at Weimar could well be described as a garnering of a degree and range of experience which perhaps could be achieved in no other way. In 1779, Goethe took on the War Commission of the Grand Duchy of Saxe-Weimar, in addition to the Mines and Highways commissions. In 1782, when the chancellor of the Duchy's Exchequer left his office, Goethe agreed to act in his place for two and a half years; this post virtually made him prime minister and the principal representative of the Duchy.[20] Goethe was ennobled in 1782 (this being indicated by the "von" in his name).

As head of the Saxe-Weimar War Commission, Goethe engaged in human trafficking, negotiating the forced sale of vagabonds, criminals, and political dissidents into both the Prussian and British military during the American Revolution. Though some other German principalities also engaged in such practices, Goethe's active participation in both a mercenary slave trade, and one that sent subjects to fight against the American War of Independence, contradicted the writer's humanist literary reputation, a stance criticized by various German intellectual contemporaries. Goethe's participation in such human rights abuses contrasted markedly with his later praise for the Founding Fathers, after the Revolution's success, in his autobiography, Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit.[21]

Italy[editar | editar código-fonte]

Goethe's journey to the Italian peninsula and Sicily from 1786 to 1788 was of great significance in his aesthetic and philosophical development. His father had made a similar journey during his own youth, and his example was a major motivating factor for Goethe to make the trip. More importantly, however, the work of Johann Joachim Winckelmann had provoked a general renewed interest in the classical art of ancient Greece and Rome. Thus Goethe's journey had something of the nature of a pilgrimage to it. During the course of his trip Goethe met and befriended the artists Angelica Kauffman and Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, as well as encountering such notable characters as Lady Hamilton and Alessandro Cagliostro (see Affair of the Diamond Necklace).

He also journeyed to Sicily during this time, and wrote intriguingly that "To have seen Italy without having seen Sicily is to not have seen Italy at all, for Sicily is the clue to everything." While in Southern Italy and Sicily, Goethe encountered, for the first time genuine Greek (as opposed to Roman) architecture, and was quite startled by its relative simplicity. Winckelmann had not recognized the distinctness of the two styles.

Goethe's diaries of this period form the basis of the non-fiction Italian Journey. Italian Journey only covers the first year of Goethe's visit. The remaining year is largely undocumented, aside from the fact that he spent much of it in Venice. This "gap in the record" has been the source of much speculation over the years.

In the decades which immediately followed its publication in 1816 Italian Journey inspired countless German youths to follow Goethe's example. This is pictured, somewhat satirically, in George Eliot's Middlemarch.

Weimar[editar | editar código-fonte]

In late 1792, Goethe took part in the battle of Valmy against revolutionary France, assisting Duke Carl August of Saxe-Weimar during the failed invasion of France. Again during the Siege of Mainz he assisted Carl August as a military observer. His written account of these events can be found within his Complete Works.

In 1794 Friedrich Schiller wrote to Goethe offering friendship; they had previously had only a mutually wary relationship ever since first becoming acquainted in 1788. This collaborative friendship lasted until Schiller's death in 1805.

In 1806, Goethe was living in Weimar with his mistress Christiane Vulpius, the sister of Christian A Vulpius, and their son Julius August Walter von Goethe. On 13 October, Napoleon's army invaded the town. The French "spoon guards," the least disciplined soldiers, occupied Goethe's house:

The 'spoon guards' had broken in, they had drunk wine, made a great uproar and called for the master of the house. Goethe's secretary Riemer reports: 'Although already undressed and wearing only his wide nightgown... he descended the stairs towards them and inquired what they wanted from him.... His dignified figure, commanding respect, and his spiritual mien seemed to impress even them.' But it was not to last long. Late at night they burst into his bedroom with drawn bayonets. Goethe was petrified, Christiane raised a lot of noise and even tangled with them, other people who had taken refuge in Goethe’s house rushed in, and so the marauders eventually withdrew again. It was Christiane who commanded and organized the defense of the house on the Frauenplan. The barricading of the kitchen and the cellar against the wild pillaging soldiery was her work. Goethe noted in his diary: "Fires, rapine, a frightful night... Preservation of the house through steadfastness and luck." The luck was Goethe’s, the steadfastness was displayed by Christiane.[22]

Days afterward, on 19 October 1806, Goethe legitimized their 18-year relationship by marrying Christiane in a quiet marriage service at the Jakobskirche in Weimar. They had already had several children together by this time, including their son, Julius August Walter von Goethe (25 December 1789 – 28 October 1830), whose wife, Ottilie von Pogwisch (31 October 1796 – 26 October 1872), cared for the elder Goethe until his death in 1832. The younger couple had three children: Walther, Freiherr von Goethe (9 April 1818 – 15 April 1885), Wolfgang, Freiherr von Goethe (18 September 1820 – 20 January 1883) and Alma von Goethe (29 October 1827 – 29 September 1844). Christiane von Goethe died in 1816.

Later life[editar | editar código-fonte]

After 1793, Goethe devoted his endeavours primarily to literature. By 1820, Goethe was on amiable terms with Kaspar Maria von Sternberg.

In 1823, having recovered from a near fatal heart illness, Goethe fell in love with Ulrike von Levetzow whom he wanted to marry, but because of the opposition of her mother he never proposed. Their last meeting in Carlsbad on 5 September 1823 inspired him to the famous Marienbad Elegy which he considered one of his finest works.[23] During that time he also developed a deep emotional bond with the Polish pianist Maria Agata Szymanowska.{{carece de fontes}}

Death[editar | editar código-fonte]

In 1832, Goethe died in Weimar of apparent heart failure. His last words, according to his doctor Carl Vogel, were, "Mehr Licht!" ("More light!'), but this is disputed as Vogel was not in the room at the moment Goethe died.[24] He is buried in the Ducal Vault at Weimar's Historical Cemetery.

Eckermann closes his famous work, Conversations with Goethe, with this passage:

The morning after Goethe's death, a deep desire seized me to look once again upon his earthly garment. His faithful servant, Frederick, opened for me the chamber in which he was laid out. Stretched upon his back, he reposed as if asleep; profound peace and security reigned in the features of his sublimely noble countenance. The mighty brow seemed yet to harbour thoughts. I wished for a lock of his hair; but reverence prevented me from cutting it off. The body lay naked, only wrapped in a white sheet; large pieces of ice had been placed near it, to keep it fresh as long as possible. Frederick drew aside the sheet, and I was astonished at the divine magnificence of the limbs. The breast was powerful, broad, and arched; the arms and thighs were elegant, and of the most perfect shape; nowhere, on the whole body, was there a trace of either fat or of leanness and decay. A perfect man lay in great beauty before me; and the rapture the sight caused me made me forget for a moment that the immortal spirit had left such an abode. I laid my hand on his heart – there was a deep silence – and I turned away to give free vent to my suppressed tears.

The first production of Richard Wagner's opera Lohengrin took place in Weimar in 1850. The conductor was Franz Liszt, who chose the date 28 August in honour of Goethe, who was born on 28 August 1749.[25]

Literary work[editar | editar código-fonte]

The most important of Goethe's works produced before he went to Weimar were Götz von Berlichingen (1773), a tragedy that was the first work to bring him recognition, and the novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (German: Die Leiden des jungen Werthers) (1774), which gained him enormous fame as a writer in the Sturm und Drang period which marked the early phase of Romanticism. Indeed, Werther is often considered to be the "spark" which ignited the movement, and can arguably be called the world's first "best-seller." During the years at Weimar before he met Schiller he began Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship, wrote the dramas Iphigenie auf Tauris (Iphigenia in Tauris), Egmont, Torquato Tasso, and the fable Reineke Fuchs.

To the period of his friendship with Schiller belong the conception of Wilhelm Meister's Journeyman Years (the continuation of Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship), the idyll of Hermann and Dorothea, the Roman Elegies and the verse drama The Natural Daughter. In the last period, between Schiller's death, in 1805, and his own, appeared Faust Part One, Elective Affinities, the West-Eastern Divan (a collection of poems in the Persian style, influenced by the work of Hafez), his autobiographical Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit (From My Life: Poetry and Truth) which covers his early life and ends with his departure for Weimar, his Italian Journey, and a series of treatises on art. His writings were immediately influential in literary and artistic circles.

Goethe was fascinated by Kalidasa's Abhijñānaśākuntalam, which was one of the first works of Sanskrit literature that became known in Europe, after being translated from English to German.[26]

Faust Part Two was only finished in the year of his death, and was published posthumously. Also published after his death was the so-called Urfaust, the first sketches, made probably in 1773–74. [27]

The short epistolary novel, Die Leiden des jungen Werthers, or The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774, recounts an unhappy romantic infatuation that ends in suicide. Goethe admitted that he "shot his hero to save himself": a reference to Goethe's own near-suicidal obsession with a young woman during this period, an obsession he quelled through the writing process. The novel remains in print in dozens of languages and its influence is undeniable; its central hero, an obsessive figure driven to despair and destruction by his unrequited love for the young Lotte, has become a pervasive literary archetype. The fact that Werther ends with the protagonist's suicide and funeral—a funeral which "no clergyman attended"—made the book deeply controversial upon its (anonymous) publication, for on the face of it, it appeared to condone and glorify suicide. Suicide is considered sinful by Christian doctrine: suicides were denied Christian burial with the bodies often mistreated and dishonoured in various ways; in corollary, the deceased's property and possessions were often confiscated by the Church.[28] However, Goethe explained his use of Werther in his autobiography. He said he "turned reality into poetry but his friends thought poetry should be turned into reality and the poem imitated." He was against this reading of poetry.[29] Epistolary novels were common during this time, letter-writing being a primary mode of communication. What set Goethe's book apart from other such novels was its expression of unbridled longing for a joy beyond possibility, its sense of defiant rebellion against authority, and of principal importance, its total subjectivity: qualities that trailblazed the Romantic movement.

The next work, his epic closet drama Faust, was to be completed in stages, and only published in its entirety after his death. The first part was published in 1808 and created a sensation. The first operatic version, by Spohr, appeared in 1814, and was subsequently the inspiration for operas and oratorios by Schumann, Berlioz, Gounod, Boito, Busoni, and Schnittke as well as symphonic works by Liszt, Wagner, and Mahler. Faust became the ur-myth of many figures in the 19th century. Later, a facet of its plot, i.e., of selling one's soul to the devil for power over the physical world, took on increasing literary importance and became a view of the victory of technology and of industrialism, along with its dubious human expenses. In 1919, the Goetheanum staged the world premiere of a complete production of Faust. On occasion, the play is still staged in Germany and other parts around the world.

Goethe's poetic work served as a model for an entire movement in German poetry termed Innerlichkeit ("introversion") and represented by, for example, Heine. Goethe's words inspired a number of compositions by, among others, Mozart, Beethoven (who idolised Goethe),[31] Schubert, Berlioz and Wolf. Perhaps the single most influential piece is "Mignon's Song" which opens with one of the most famous lines in German poetry, an allusion to Italy: "Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühn?" ("Do you know the land where the lemon trees bloom?").

He is also widely quoted. Epigrams such as "Against criticism a man can neither protest nor defend himself; he must act in spite of it, and then it will gradually yield to him", "Divide and rule, a sound motto; unite and lead, a better one", and "Enjoy when you can, and endure when you must", are still in usage or are often paraphrased. Lines from Faust, such as "Das also war des Pudels Kern", "Das ist der Weisheit letzter Schluss", or "Grau ist alle Theorie" have entered everyday German usage.

It may be taken as another measure of Goethe's fame that other well-known quotations are often incorrectly attributed to him, such as Hippocrates' "Art is long, life is short", which is found in Goethe's Faust ("Art is something so long to be learned, and life is so short!") and Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship.

Scientific work[editar | editar código-fonte]

As to what I have done as a poet,... I take no pride in it... But that in my century I am the only person who knows the truth in the difficult science of colours – of that, I say, I am not a little proud, and here I have a consciousness of a superiority to many.

– Johann Eckermann, Conversations with Goethe

Although his literary work has attracted the greatest amount of interest, Goethe was also keenly involved in studies of natural science.[32] He wrote several works on morphology, and colour theory. Goethe also had the largest private collection of minerals in all of Europe. By the time of his death, in order to gain a comprehensive view in geology, he had collected 17,800 rock samples.

His focus on morphology and what was later called homology influenced 19th century naturalists, although his ideas of transformation were about the continuous metamorphosis of living things and did not relate to contemporary ideas of "transformisme" or transmutation of species. Homology, or as Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire called it "analogie", was used by Charles Darwin as strong evidence of common descent and of laws of variation.[33] Goethe's studies (notably with an elephant's skull lent to him by Samuel Thomas von Soemmerring) led him to independently discover the human intermaxillary bone in 1784, which Broussonet (1779) and Vicq d'Azyr (1780) had (using different methods) identified several years earlier.[34] While not the only one in his time to question the prevailing view that this bone did not exist in humans, Goethe, who believed ancient anatomists had known about this bone, was the first to prove its peculiarity to all mammals. The elephant's skull that led Goethe to this discovery, and was subsequently named the Goethe Elephant, still exists and is displayed in the Ottoneum in Kassel, Germany.

During his Italian journey, Goethe formulated a theory of plant metamorphosis in which the archetypal form of the plant is to be found in the leaf – he writes, "from top to bottom a plant is all leaf, united so inseparably with the future bud that one cannot be imagined without the other".[35] In 1790, he published his Metamorphosis of Plants.[36] As one of the many precursors in the history of evolutionary thought, Goethe wrote in Story of My Botanical Studies (1831):

The ever-changing display of plant forms, which I have followed for so many years, awakens increasingly within me the notion: The plant forms which surround us were not all created at some given point in time and then locked into the given form, they have been given... a felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.[37]

Goethe's botanical theories were partly based on his gardening in Weimar.[38]

Goethe also popularized the Goethe barometer using a principle established by Torricelli. According to Hegel, "Goethe has occupied himself a good deal with meteorology; barometer readings interested him particularly... What he says is important: the main thing is that he gives a comparative table of barometric readings during the whole month of December 1822, at Weimar, Jena, London, Boston, Vienna, Töpel... He claims to deduce from it that the barometric level varies in the same propoportion not only in each zone but that it has the same variation, too, at different altitudes above sea-level".[39]

In 1810, Goethe published his Theory of Colours, which he considered his most important work. In it, he contentiously characterized colour as arising from the dynamic interplay of light and darkness through the mediation of a turbid medium.[40] In 1816, Schopenhauer went on to develop his own theory in On Vision and Colours based on the observations supplied in Goethe's book. After being translated into English by Charles Eastlake in 1840, his theory became widely adopted by the art world, most notably J. M. W. Turner.[41] Goethe's work also inspired the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, to write his Remarks on Colour. Goethe was vehemently opposed to Newton's analytic treatment of colour, engaging instead in compiling a comprehensive rational description of a wide variety of colour phenomena. Although the accuracy of Goethe's observations does not admit a great deal of criticism, his theory's failure to demonstrate significant predictive validity eventually rendered it scientifically irrelevant{{carece de fontes}}. Goethe was, however, the first to systematically study the physiological effects of colour, and his observations on the effect of opposed colours led him to a symmetric arrangement of his colour wheel, 'for the colours diametrically opposed to each other... are those which reciprocally evoke each other in the eye. (Goethe, Theory of Colours, 1810).[42] In this, he anticipated Ewald Hering's opponent colour theory (1872).[43]

Goethe outlines his method in the essay The experiment as mediator between subject and object (1772).[44] In the Kurschner edition of Goethe's works, the science editor, Rudolf Steiner, presents Goethe's approach to science as phenomenological. Steiner elaborated on that in the books The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception[45] and Goethe's World View,[46] in which he characterizes intuition as the instrument by which one grasps Goethe's biological archetype—The Typus.

Novalis, himself a geologist and mining engineer, expressed the opinion that Goethe was the first physicist of his time and 'epoch-making in the history of physics', writing that Goethe's studies of light, of the metamorphosis of plants and of insects were indications and proofs 'that the perfect educational lecture belongs in the artist's sphere of work'; and that Goethe would be surpassed 'but only in the way in which the ancients can be surpassed, in inner content and force, in variety and depth – as an artist actually not, or only very little, for his rightness and intensity are perhaps already more exemplary than it would seem'. [47]

Eroticism[editar | editar código-fonte]

Many of Goethe's works, especially Faust, the Roman Elegies, and the Venetian Epigrams, depict erotic passions and acts. For instance, in Faust, the first use of Faust's power after literally signing a contract with the devil is to fall in love with and impregnate a teenage girl. Some of the Venetian Epigrams were held back from publication due to their sexual content. Goethe clearly saw human sexuality as a topic worthy of poetic and artistic depiction, an idea that was uncommon in a time when the private nature of sexuality was rigorously normative.[48]

Goethe wrote of both boys and girls: “I like boys a lot, but the girls are even nicer. If I tire of her as a girl, she’ll play the boy for me as well” (Goethe, 1884).[49] Goethe also defended pederasty: "Pederasty is as old as humanity itself, and one can therefore say that it is natural, that it resides in nature, even if it proceeds against nature. What culture has won from nature will not be surrendered or given up at any price."[50]

Religion and politics[editar | editar código-fonte]

Goethe was a freethinker who believed that one could be inwardly Christian without following any of the Christian churches, many of whose central teachings he firmly opposed, sharply distinguishing between Christ and the tenets of Christian theology, and criticizing its history as a "hodgepodge of fallacy and violence".[51][52][53] His own descriptions of his relationship to the Christian faith and even to the Church varied widely and have been interpreted even more widely, so that while Goethe's secretary Eckermann portrayed him as enthusiastic about Christianity, Jesus, Martin Luther, and the Protestant Reformation, even calling Christianity the "ultimate religion,"[54][55][56] on one occasion Goethe described himself as "not anti-Christian, nor un-Christian, but most decidedly non-Christian,"[57] and in his Venetian Epigram 66, Goethe listed the symbol of the cross among the four things that he most disliked.[58][59] According to Nietzsche, Goethe had "a kind of almost joyous and trusting fatalism" that has "faith that only in the totality everything redeems itself and appears good and justified."[60]

Born into a Lutheran family, Goethe's early faith was shaken by news of such events as the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and the Seven Years' War. His later spiritual perspective incorporated elements of pantheism (heavily influenced by Spinoza), humanism, and various elements of Western esotericism, as seen most vividly in Part II of Faust. A year before his death, in a letter to Sulpiz Boisserée, Goethe wrote that he had the feeling that all his life he had been aspiring to qualify as one of the Hypsistarians, an ancient Jewish-pagan sect of the Black Sea region who, in his understanding, sought to reverence, as being close to the Godhead, what came to their knowledge of the best and most perfect.[61]

In politics, Goethe was conservative. At the time of the French Revolution, he thought the enthusiasm of the students and professors to be a perversion of their energy and remained skeptical of the ability of the masses to govern.[62] Likewise, he did not oppose the War of Liberation (1813–15) waged by the German states against Napoleon, and remained aloof from the patriotic efforts to unite the various parts of Germany into one nation.

Although often requested to write poems arousing nationalist passions, Goethe would always decline. In old age, he explained why this was so to Eckermann:

How could I write songs of hatred when I felt no hate? And, between ourselves, I never hated the French, although I thanked God when we were rid of them. How could I, to whom the only significant things are civilization [Kultur] and barbarism, hate a nation which is among the most cultivated in the world, and to which I owe a great part of my own culture? In any case this business of hatred between nations is a curious thing. You will always find it more powerful and barbarous on the lowest levels of civilization. But there exists a level at which it wholly disappears, and where one stands, so to speak, above the nations, and feels the weal or woe of a neighboring people as though it were one's own.[63]

Influence[editar | editar código-fonte]

Goethe had a great effect on the nineteenth century. In many respects, he was the originator of many ideas which later became widespread. He produced volumes of poetry, essays, criticism, a theory of colours and early work on evolution and linguistics. He was fascinated by mineralogy, and the mineral goethite (iron oxide) is named after him.[64] His non-fiction writings, most of which are philosophic and aphoristic in nature, spurred the development of many philosophers, including Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Schopenhauer, Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Ernst Cassirer, Carl Jung, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Along with Schiller, he was one of the leading figures of Weimar Classicism. Schopenhauer cited Goethe's novel Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship as one of the four greatest novels ever written, along with Tristram Shandy, La Nouvelle Héloïse and Don Quixote.[5]

Goethe embodied many of the contending strands in art over the next century: his work could be lushly emotional, and rigorously formal, brief and epigrammatic, and epic. He would argue that Classicism was the means of controlling art, and that Romanticism was a sickness, even as he penned poetry rich in memorable images, and rewrote the formal rules of German poetry. Even in contemporary culture, he stands in the background as the author of the ballad that formed the basis for Walt Disney Pictures' The Sorcerer's Apprentice, produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and directed by Jon Turteltaub. The film was based on the relevant section of Disney's animated film Fantasia (1940), which was set to a short scherzo for orchestra by Paul Dukas, L'apprenti sorcier (The Sorcerer's Apprentice, published in 1897, and by far, the best known of Dukas' compositions). All of which were inspired by Goethe's poem, The Sorcerer's Apprentice.[65]

His poetry was set to music by almost every major Austrian and German composer from Mozart to Mahler, and his influence would spread to French drama and opera as well. Beethoven declared that a "Faust" Symphony would be the greatest thing for art. Liszt and Mahler both created symphonies in whole or in large part inspired by this seminal work, which would give the 19th century one of its most paradigmatic figures: Doctor Faustus.

The Faust tragedy/drama, often called Das Drama der Deutschen (the drama of the Germans), written in two parts published decades apart, would stand as his most characteristic and famous artistic creation. Followers of the twentieth century esotericist Rudolf Steiner built a theatre named the Goetheanum after him—where festival performances of Faust are still performed.

Goethe was also a cultural force, who argued that the organic nature of the land moulded the people and their customs—an argument that has recurred ever since. He argued that laws could not be created by pure rationalism, since geography and history shaped habits and patterns. This stood in sharp contrast to the prevailing Enlightenment view that reason was sufficient to create well-ordered societies and good laws.

It was to a considerable degree due to Goethe's reputation that the city of Weimar was chosen in 1919 as the venue for the national assembly, convened to draft a new constitution for what would become known as Germany's Weimar Republic.

The Federal Republic of Germany's cultural institution, the Goethe-Institut is named after him, and promotes the study of German abroad and fosters knowledge about Germany by providing information on its culture, society and politics.

The literary estate of Goethe in the Goethe and Schiller Archives was inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2001 in recognition of its historical significance.[66]

Goethe's influence was dramatic because he understood that there was a transition in European sensibilities, an increasing focus on sense, the indescribable, and the emotional. This is not to say that he was emotionalistic or excessive; on the contrary, he lauded personal restraint and felt that excess was a disease: "There is nothing worse than imagination without taste". He argued in his scientific works that a "formative impulse", which he said is operative in every organism, causes an organism to form itself according to its own distinct laws, and therefore rational laws or fiats could not be imposed at all from a higher, transcendent sphere; this placed him in direct opposition to those who attempted to form "enlightened" monarchies based on "rational" laws by, for example, Joseph II of Austria or the subsequent Emperor of the French, Napoleon I. He said in Scientific Studies:

We conceive of the individual animal as a small world, existing for its own sake, by its own means. Every creature is its own reason to be. All its parts have a direct effect on one another, a relationship to one another, thereby constantly renewing the circle of life; thus we are justified in considering every animal physiologically perfect. Viewed from within, no part of the animal is a useless or arbitrary product of the formative impulse (as so often thought). Externally, some parts may seem useless because the inner coherence of the animal nature has given them this form without regard to outer circumstance. Thus...[not] the question, What are they for? but rather, Where do they come from?[67]

That change later became the basis for 19th-century thought: organic rather than geometrical, evolving rather than created, and based on sensibility and intuition rather than on imposed order, culminating in, as Goethe said, a "living quality", wherein the subject and object are dissolved together in a poise of inquiry. Consequently, Goethe embraced neither teleological nor deterministic views of growth within every organism. Instead, his view was that the world as a whole grows through continual, external, and internal strife. Moreover, Goethe did not embrace the mechanistic views that contemporaneous science subsumed during his time, and therewith he denied rationality's superiority as the sole interpreter of reality.

His views make him, along with Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, and Ludwig van Beethoven, a figure in two worlds: on the one hand, devoted to the sense of taste, order, and finely crafted detail, which is the hallmark of the artistic sense of the Age of Reason and the neo-classical period of architecture; on the other, seeking a personal, intuitive, and personalized form of expression and society, firmly supporting the idea of self-regulating and organic systems.

Thinkers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson would take up many similar ideas in the 1800s. Goethe's ideas on evolution would frame the question that Darwin and Wallace would approach within the scientific paradigm. The Serbian inventor and electrical engineer Nikola Tesla was heavily influenced by Goethe's Faust, his favorite poem, and had actually memorized the entire text. It was while reciting a certain verse that he was struck with the epiphany that would lead to the idea of the rotating magnetic field and ultimately, alternating current.[68]

Bibliography[editar | editar código-fonte]

- The Life of Goethe by George Henry Lewes

- Goethe: The History of a Man by Emil Ludwig

- Goethe by Georg Brandes. Authorized translation from the Danish (2nd ed. 1916) by Allen W. Porterfield, New York, Crown publishers, 1936. "Crown edition, 1936." Title Wolfgang Goethe

- Goethe: his life and times by Richard Friedenthal

- Lotte in Weimar: The Beloved Returns by Thomas Mann

- Conversations with Goethe by Johann Peter Eckermann

- Goethe's World: as seen in letters and memoirs ed. by Berthold Biermann

- Goethe: Four Studies by Albert Schweitzer

- Goethe Poet and Thinker by E. M. Wilkinson and L. A. Willoughby

- Goethe and his Publishers by Siegfried Unseld

- Goethe by T. J. Reed

- Goethe. A Psychoanalytic Study, by Kurt R. Eissler

- The Life of Goethe. A Critical Biography by John Williams

- Goethe: The Poet and the Age (2 Vols.), by Nicholas Boyle

- Goethe's Concept of the Daemonic: After the Ancients, by Angus Nicholls

- Goethe and Rousseau: Resonances of their Mind, by Carl Hammer, Jr.

- Doctor Faustus of the popular legend, Marlowe, the Puppet-Play, Goethe, and Lenau, treated historically and critically.-A parallel between Goethe and Schiller.-An historic outline of German Literature , by Louis Pagel

- Goethe and Schiller, Essays on German Literature, by Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen

- Tales for Transformation, trans. Scott Thompson

- Goethe-Wörterbuch (Goethe Dictionary, abbreviated GWb). Herausgegeben von der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen und der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Stuttgart. Verlag W. Kohlhammer; ISBN 978-3-17-019121-1

See also[editar | editar código-fonte]

- Young Goethe in Love (2010)

- Dora Stock – her encounters with the 16-year-old Goethe.

- Goethe Basin

- Johann-Wolfgang-von-Goethe-Gymnasium

- W. H. Murray – author of misattributed quotation "Until one is committed ..."

- Nature (Tobler essay), essay often mis-attributed to Goethe

- Awards named after him

References[editar | editar código-fonte]

- ↑ "Goethe". Oxford Dictionary.

- ↑ "Goethe". Merriam Webster Dictionary.

- ↑ "Goethe". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ «Classical Weimar UNESCO Justification». Justification for UNESCO Heritage Cites. UNESCO. Consultado em 7 June 2012 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ a b Schopenhauer, Arthur. «The Art of Literature». The Essays of Arthur Schopenahuer. Consultado em 22 March 2015 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ a b Herman Grimm: Goethe. Vorlesungen gehalten an der Königlichen Universität zu Berlin. Vol. 1. J.G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger, Stuttgart / Berlin 1923, p. 36

- ↑ Catharina was the daughter of Johann Wolfgang Textor, sheriff (Schultheiß) of Frankfurt, and Anna Margaretha Lindheimer.

- ↑ von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang. The Autobiography of Goethe: truth and poetry, from my own life, Volume 1 (1897), translated by John Oxenford, pp. 114, 129

- ↑ Valerian Tornius: Goethe – Leben, Wirken und Schaffen. Ludwig-Röhrscheid-Verlag, Bonn 1949, p. 26

- ↑ Emil Ludwig: Goethe – Geschichte eines Menschen. Vol. 1. Ernst-Rowohlt-Verlag, Berlin 1926, p. 17–18

- ↑ Karl Goedeke: Goethes Leben. Cotta / Kröner, Stuttgart around 1883, p. 16–17

- ↑ «Originally speech of Goethe to the ''Shakespeare's Day'' by University Duisburg». Uni-duisburg-essen.de. Consultado em 17 July 2014 Verifique data em:

|acessodata=(ajuda) - ↑ Herman Grimm: Goethe. Vorlesungen gehalten an der Königlichen Universität zu Berlin. Vol. 1. J. G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger, Stuttgart / Berlin 1923, p. 81

- ↑ Karl Robert Mandelkow, Bodo Morawe: Goethes Briefe. 2. edition. Vol. 1: Briefe der Jahre 1764–1786. Christian Wegner, Hamburg 1968, p. 571

- ↑ Valerian Tornius: Goethe — Leben, Wirken und Schaffen. Ludwig-Röhrscheid-Verlag, Bonn 1949, p.60

- ↑ a b Mandelkow, Karl Robert (1962). Goethes Briefe. Vol. 1: Briefe der Jahre 1764–1786. Christian Wegner Verlag. p. 589

- ↑ Mandelkow, Karl Robert (1962). Goethes Briefe. Vol. 1: Briefe der Jahre 1764–1786. Christian Wegner Verlag. p. 590-592

- ↑ See Goethe and his Publishers

- ↑ Charlotte Von Stein. Classic Encyclopedia, retrieved 14 April 2011

- ↑ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe – Britannica.com

- ↑ Wilson, W. Daniel (1999). Das Goethe-Tabu [The Goethe Taboo: Protest and Human Rights in Classical Weimar] (em German). Munich: Deutsche Taschenbuch Verlag (dtv). pp. 49–57, also the entire book. ISBN 3-423-30710-2; "The Goethe Case by W. Daniel Wilson" – The New York Review of Books.

- ↑ Safranski, Rüdiger (1990). Schopenhauer and the Wild Years of Philosophy. [S.l.]: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-79275-0

- ↑ «Goethe's third summer»

- ↑ Carl Vogel: Die letzte Krankheit Goethe’s. In: Journal der practischen Heilkunde (1833).

- ↑ Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th ed., 1954